Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

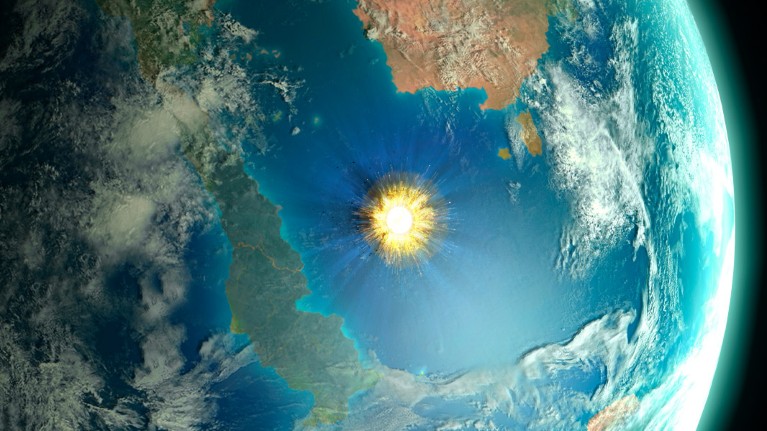

Credit: Mark Garlick/Science Photo Library

Dinosaurs might have met a dusty end

Dust might have been responsible for the deadly dinosaur-killing global winter that came after an asteroid slammed into Earth 66 million years ago. Climate simulations suggest that the impact kicked up enough fine particles to block out the Sun and prevent plants from photosynthesizing for up to two years. The dust might have stayed in the atmosphere for some 15 years, which resulted in global temperatures dropping by as much as 15 ℃.

Nature | 3 min read

Reference: Nature Geoscience paper

Embryos show space babies might be OK

Frozen mouse embryos that were defrosted in space and cultured for four days on the International Space Station (ISS) seem to have been unharmed by microgravity or radiation. The finding, along with evidence from pregnant rats that spent a few days on the ISS, suggests that it might one day be safe for people to reproduce in space. More research is needed — and as part of the most recent study, researchers developed a device for thawing and culturing embryos so that astronauts can easily perform more experiments.

New Scientist | 3 min read

Reference: iScience paper

Seals help scientists to map ocean floor

Researchers have discovered an underwater canyon in the Antarctic Ocean, thanks to deep-diving seals. More than 200 southern elephant seals (Mirounga leonina) were fitted with trackers to find places where the animals dove deeper than would be possible according to existing maps. Sonar measurements later confirmed the existence of a canyon plunging to depths of more than two kilometres. These deep-sea-floor structures play a part in ice-melting physics, because they allow warmer water to flow to the coast.

Scientific American | 2 min read

Reference: Communications Earth & Environment paper

Features & opinion

Plan S: the next generation

The group behind the open-access initiative Plan S has announced a proposal to go one step further. cOAlition S triggered a seismic shift in scholarly communication by convening an influential group of research funders who pledged that the science they bankrolled would be published outside journal paywalls. Now it wants all versions of an article and its associated peer-review reports to be published openly from the outset, without authors paying any fees, and for authors, rather than publishers, to decide when and where to first publish their work. Plan S was criticized for not including much feedback from the research community; this time, cOAlition S says it will revise the strategy on the basis of the results of a six-month consultation process.

Nature | 11 min read

(Nature, and this Briefing, is editorially independent of its publisher, Springer Nature.)

Consciousness is still a mystery

The scientific debate around consciousness is livelier than ever: what it is, where it comes from and whether machines can have it. Cognitive neuroscientist Liad Mudrik reviews three books that tackle these thorny questions. The authors — philosopher Daniel Dennett, geneticist Kevin Mitchell and neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux — agree that consciousness gave humans an evolutionary edge. Dennett and LeDoux argue that consciousness can exist only in biological beings, but Mitchell suggests that artificial systems could follow our evolutionary trajectory: embodiment, sensing, acting, with some motivation and learning abilities, and a drop of indeterminacy. Whether this is a good idea, writes Mudrik, is a different question.

Nature | 9 min read

How to get your paper accepted

Up to 50% of papers get rejected before they are sent for peer review. Tourism researcher Cheong Fan has three tips for how to avoid these frustrating rejections:

• Consider your target journal’s scope when establishing your research ideas and composing your article

• Be clear about how your research fills knowledge gaps

• Ensure your methods align with your study’s aim

Times Higher Education | 5 min read

Infographic of the week

Scientists compiled data from how people around the world allocate their time to define the ‘global human day’. We spend most of our almost 15 waking hours on things that directly affect ourselves and others. The remaining time goes to changing the physical world (activities as wide-ranging as farming, cleaning, manufacturing and construction) and less tangible activities such as government work, retail and transportation. (Scientific American | 3 min read) (Studio Terp; Source: W. Fajzel et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci USA 120, e2219564120 (2023) (data))