President Donald J. Trump made many promises about what he would do on his first day in office. It might have seemed unlikely that he would come for arts institutions that early, but in fact, national museums got caught up in his dragnet against programs ensuring diversity, equity, inclusion, and access (DEIA), programs he called “illegal and immoral” in a January 20 executive order. Both the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Smithsonian Institution, a nationwide network of museums, scrapped their DEIA offices within a week.

That’s just one of many ways the Trump administration has mounted what is widely viewed as an attack on museums and all that they stand for in a democratic society. Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) has taken a wrecking ball to crucial federal agencies that fund museums; Trump has dispatched vice president J.D. Vance and a Florida insurance lawyer to root out any examples of what he deems un-American speech at Smithsonian museums; and, most recently, DOGE staffers have even paid a visit to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., at which they, ominously, “discussed the museum’s legal status.”

Experts are unequivocal about this moment’s historic significance.

“There is no precedent for the moment we are in,” said Marilyn Jackson, president and CEO of the American Alliance of Museums.

National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Photo: Shutterstock.

“It feels like an assault and I think we can fairly describe it as a culture war,” said Anne Ellegood, director of the Institute of Contemporary Art Los Angeles.

“This administration has declared war on the nonprofit sector,” said philanthropy consultant Melissa Cowley Wolf. “It’s a lot to keep up with and it’s continuously devastating if you care about the work of civil society.”

“I think this is absolute watershed moment,” said Carin Kuoni, senior director and chief curator at the Vera List Center for Art and Politics at the New School in New York. “I don’t think we’ve seen anything like it. The assault on civic institutions is so profound and so structural that they won’t recover very quickly. We’re looking at a changed landscape that we can’t quite see yet but it is changing how nonprofits exist in this country.”

“Museums that are reliant on major federal grants are dealing with a heat that is unprecedented and almost unnavigable,” said Brett Egan, president at Washington, D.C.’s DeVos Institute of Arts and Nonprofit Management and formerly director of the DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the Kennedy Center in Washington. “You can’t win.”

“Everyone is very scared of speaking up,” one museum director said. Indeed, many requests for interviews for this article, sent to a dozen major public and private art and science museums around the country, were answered with silence or messages like “We’re going to politely pass.”

The fear is understandable—anyone who takes positions against Trump’s policies is likely to come under attack—or worse—by the president. This has been especially evident when it comes to his crackdown on immigrants. Last month, Trump called moderate judge James E. Boasberg a “radical left lunatic” after he ruled against the administration’s attempts to unlawfully disappear immigrants based on an obscure wartime legal provision. A Milwaukee circuit court judge, Hannah Dugan, was even arrested in late April when she helped a man in her court to evade immigration authorities who showed up to arrest him but had no warrant.

A few highly placed figures within federally funded cultural institutions have left or been removed from their jobs since January. This includes Shelly Lowe, chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and the first Native American to hold the role, who left her position in March “at the direction of President Trump,” the agency said in a statement. Still unexplained is the March 14 departure of poet Kevin Young from the director position at the Smithsonian Institutions’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), which Trump had previously criticized in his first term. In February, the president was also “unanimously” elected chairman of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts after ousting longtime president Deborah Rutter and appointing several allies.

A Cavalcade of Acts

What followed the DEIA executive order on January 20 was an incredible array of similar orders and other acts by Trump and Musk that have taken aim at museums and the organizations that have typically doled out federal funds to them, either destroying them or asserting control over them.

President Donald Trump signs executive orders in the Oval Office on January 20, 2025 in Washington, D.C. Photo: Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images.

Trump repeatedly tried to eliminate the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) in his first term; this time around, he apparently sees a new purpose for the agency in promoting patriotic programming. Not three weeks after Trump was inaugurated, the NEA canceled its Challenge America grants, focused on underserved communities, and announced updated guidelines for grant applicants, encouraging them to focus on patriotic projects that honor the 250th anniversary of the nation’s founding.

Trump’s funding decisions seem partly driven by personal grudges, as suggested by the cancelation of an exhibition about a perceived adversary: funding was revoked on February 9 for an exhibition at the National Museum of Health and Medicine on Anthony Fauci, former director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The DEIA freeze, meanwhile, extended to scrapping individual shows, one devoted to Black artists and one devoted to Canadian LGBTQ artists, both scheduled to take place at D.C.’s Art Museum of the Americas.

Even if the NEA survived DOGE’s wrecking ball, other museum funding agencies were not so lucky. Trump promptly came for what is probably the most important source of museum funds that even many in the art world hadn’t heard of: the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). An executive order directed severe cuts at the organization, and DOGE descended upon its headquarters on March 17, installing a new acting head of the organization; DOGE then placed the staff on administrative leave on March 31.

Vacant office space at the Institute for Museum and Library Services in Washington, D.C.

The IMLS cuts alone would mean eliminating 891 open awards to museums with $180 million in federal funds. What’s more, in most cases, museums had already spent the funds and were slated to get reimbursed under the terms of their contracts, but that money will not be repaid, voiding legal contracts with the museums and leaving them in the lurch. It also soon emerged that DOGE was calling for major cuts at the NEH, and that funds from its budget would go toward a patriotic “Garden of Heroes.”

At the end of March, Trump demanded that museums under the umbrella of the Smithsonian Institution remove traces of what he deems anti-American ideologies, specifically naming the Smithsonian American Art Museum for an exhibition he said promoted a “divisive, race-centered ideology;” the NMAAHC for the way it described “White culture;” and the American Women’s History Museum for its plan to celebrate “the exploits of male athletes participating in women’s sports,” referring to transgender women, whom he considers men.

Museum leadership have been pushed back on their heels, and they don’t know what’s yet to come. “We might experience certain pressures we haven’t even anticipated yet,” said ICA L.A.’s Ellegood. Financial crises and the COVID-19 pandemic have represented body blows to traditional funding models even before January 20, she pointed out, and the rapid-fire changes since then—not to mention massive hits to the principal balances in museums’ endowments amid plummeting financial markets—present a tremendous challenge.

Institute of Contemporary Art Los Angeles. Photo: Jeff McLane/ICA LA.

“One of the frustrations is the amount of time it takes to monitor these things and make changes,” Ellegood said. “Should we even apply for NEA funding or are they going to get rid of the whole NEA tomorrow? It’s hard to lead and manage an institution in that environment.”

What Is Really Being Lost

Opponents of government funding for culture are good at trotting out examples they consider frivolous, and they tend to focus on race. In a recent, particularly muddled New York Times editorial, Mark Bauerlein—co-author of a history of the NEA and a former employee there—criticized an NEH grant awarded to San Diego State University to create a “social justice curriculum based on comic books.” DOGE bragged in an X (formerly Twitter) post about cutting, among others, a $105,000 IMLS grant to the California Association of Museums to address systemic racism (a phrase it put in scare quotes) in museums. The California State Library shot back that its grant, also mentioned by DOGE, went to serving the blind and reading-disabled.

Mónica Ramírez-Montagut, executive director of the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, New York. Photo: Lisa Tamburini.

“There’s a misunderstanding of DEI in the public imaginary,” said Mónica Ramírez-Montagut, executive director of the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, New York, in a phone interview. Her museum has received IMLS grants, and she served on the agency’s board. “It’s not exclusively about race or gender. That’s a tremendous misconception. We oversimplify things in ways that are incredibly detrimental to all of us. It means folks living with Alzheimer’s, people with visual impairments, the Deaf community.” The most vulnerable communities will be hit the worst, she said.

The museum had been promised a $200,000 IMLS grant to create bespoke experiences for people with special needs, including cancer survivors, domestic abuse survivors, and women in the prison system; with those funds, the museum served some 2,500 people annually. One particularly memorable example, to Ramírez-Montagut, is that of a former rock drummer, now in his 70s, who has Alzheimer’s. New research indicated that drumming was especially therapeutic, she said, so the museum bought percussion instruments for him to play. “He finds his authentic self while practicing the drums,” she said. “It has a tremendous impact on his quality of life.”

School programs at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, New York.

While the NEA and the NEH are first to come to many people’s minds when public arts funding is threatened, the IMLS is also crucial. Consultant Cowley Wolf said that she often speaks before rooms full of museum development officers. “I say, ‘Raise your hands if you’ve had to apply for IMLS grants,’” she said, “and then I say, ‘Keep your hand up if it was the hardest grant application you ever wrote,’ and then I say, ‘Keep your hands up if it was the most important funding for your organization.’ The hands stay up.”

A few examples of IMLS grants from 2024 alone: The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) was promised $744,095 to research and test environmentally sustainable art packaging. The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum was to get $180,975 to create a paid apprenticeship program for registrars and art handlers (who, it said in its application, are hard to come by in the museum’s home state of New Mexico). The Denver Art Museum, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art each were to get $250,000 to increase access for visitors with disabilities. The Institute of Contemporary Art Boston was promised $130,000 for out-of-school programs with teens meant to “respond directly to the growing youth mental health crisis in the United States.”

Groups of school children outside the Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art.

Other such school programs at museums nationwide are also bound to be cut. The Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art in Virginia Beach was to receive a $32,399 IMLS grant for a two-year program in which students created nature journals, inspired by artworks by Mark Dion and Alexis Rockman, and created artwork out of debris washed up on shore in their marine community, inspired by artist Duke Riley. The museum had initially applied with a smaller project, executive director Alison Byrne said in a phone interview, but they were told, “Dream bigger.” Now they’ve spent the money and don’t anticipate reimbursement. “If we knew we weren’t going to get the IMLS money, we would have done it on a much smaller scale,” she said.

The current climate is “heartbreaking,” Byrne continued. “I feel for our museum colleagues everywhere and the communities and artists they serve. It’s the antithesis of everything we’re about. Nobody wins here. I’m looking at these kids who were here today seeing their work and seeing their names on a sign at the museum and how powerful that is.” Losing the grants, she said, would “take away so many meaningful opportunities for everyone, particularly those who are underserved, because art has the power to make connections.”

Why Museums Are Under Attack

People working in museums argue that art spaces are not simply playgrounds for the wealthy or venues for expensive artworks and exclusive events. Cowley Wolf cites the “Bilbao and Basel effect”—the trend of major art institutions like the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao and the Art Basel fair becoming symbols of cultural prestige and luxury—as a reason why many now see art spaces as exclusive, commercialized destinations, rather than accessible cultural resources for all. This impression may require powerful messaging to counteract, she warns.

DOGE’s recent moves to defund cultural agencies have largely been presented by the Trump Administration as an effective method of trimming bureaucratic budget fat. But Ramirez-Montagut argues these acts “are eroding the building blocks for a healthy democracy.” She points to one IMLS initiative introduced under Biden that was focused on digital literacy, helping people to be able to keenly identify what is real, factual news and what is not. “The country needed that kind of literacy.”

Laura Lott, formerly president and CEO of the American Alliance of Museums and, until March 2025, administrator and chief operating officer at the National Gallery of Art, said in an email that “Museums (and libraries and performing arts institutions and universities) are places where people, often from different backgrounds and perspectives, come together to learn—to be inspired, to explore different histories and perspectives. They challenge our assumptions, make us think, and help us explore nuance. Connecting, learning, and debating informs and, I believe, strengthens our democracy.”

Anne Ellegood. Photo: Howard Wise/ICA L.A.

She added that it seems that an “educated, free-thinking, debating public” is a threat to the power of this administration and, apparently, to many in Congress who she claimed are refusing to act in the face of the administration’s “irresponsible actions” including those against arts, humanities, and other cultural institutions

“They don’t want the public to understand facts and think too critically,” she said. “Rather, they’d like us to just accept the policies they’re selling without question or compromise.”

In the face of urgent calls for action on the most fundamental issues of the welfare of the American population (people, including American citizens, are after all being abducted off the streets by masked government agents and shipped out of the country with no due process), Ellegood admits, arts funding could be described as “superflous,” but “one of the arguments we need to make is that societies flourish and are better with art and culture, and that they play a huge role in developing critical thinking, which is fundamentally why Trump is doing this.”

Green Shoots of Resistance

Some museum leaders have found the courage to speak out, and some perhaps unexpected parties outside the art world have taken action.

In response to the new guidelines for NEA grantees, which required that applicants pledge not to use any federal funds to “promote gender ideology,” the American Civil Liberties Union of Rhode Island filed a lawsuit on March 6 on behalf of four theater organizations, arguing that those requirements violate the First Amendment and the Fifth Amendment. The suit won a temporary and partial victory within just days, when the NEA agreed to remove the new requirement for applying—though it did not revoke eligibility criteria stating that applicants cannot receive an award if they do promote such ideologies. Later that month, Columbia University faculty unions, which represent some artists and art and architecture history professors, brought a suit against the administration for its unlawful revoking of $400 million in federal funds and attempts to control speech at the university, after the school administration had said it would fold under the threat.

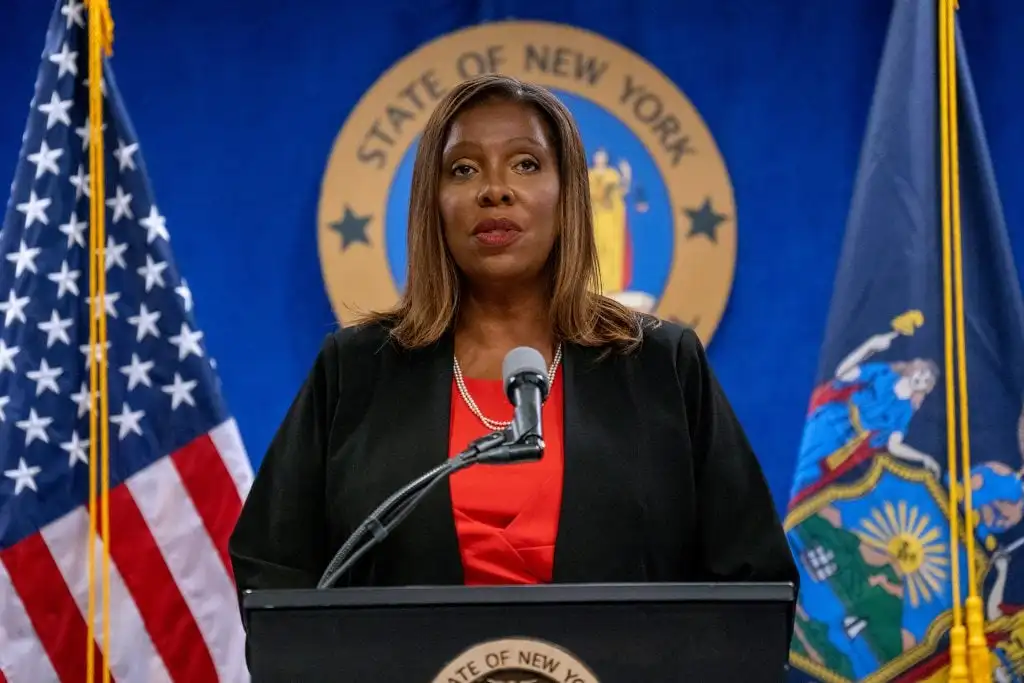

New York Attorney General Letitia James. Photo: David Dee Delgado / Getty Images.

Some 19 members of IMLS’s board, including Ramírez-Montagut, also spoke up for the agency, sending its acting head a March 24 letter pointing out statutes that require its activities to continue, including all current and multiyear grants. After getting no reply, they followed up with another on April 3, requesting information about the decision to place employees on leave and asking for open hearings. The letter writing campaign fizzled: within hours, they were relieved of their posts. On April 4, attorneys general from New York, California, Illinois, and 18 other states filed a suit against Trump and high-ranking government officials over the unlawful dismantling of agencies including IMLS.

Even those who have found fault with museums are aghast at the present situation.

“I’ve definitely been critical of museums’ board and donor structures,” said writer Ciarán Finlayson, who co-authored “The Tear Gas Biennial,” the 2019 Artforum editorial about the controversy over the presence of arms dealer Warren Kanders on the board of New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art. “But there are progressive and reactionary approaches to restructuring museums.” He described the prospect of vice president Vance having influence at the Smithsonian’s NMAAHC as “totally alarming” and saw real danger in the Stop Terror-Financing and Tax Penalties on American Hostages Act, passed by the House of Representatives in 2024, that would allow the Treasury Secretary broad powers to designate nonprofit organizations as supporters of terrorism and revoke their tax-exempt status. Finlayson called it the “non-profit-killer bill.”

Museums that focus on the experiences of non-white people would seem to be a particular target for this administration, which, remember, made wiping out DEIA a first-day priority. But some such institutions have proven to be the most vocal in their resistance to the administration.

The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). Photo: Alan Karchmer, courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

Detroit institutions that are focused on the Black experience and Black artists have pledged to keep true to their mission. The Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History’s president and chief executive Neil Barclay told the New York Times that the museum will “resist and persevere.” In the same article, Vedet Coleman-Robinson, the president and chief executive of the Association of African American Museums, said of the association’s members, “I have not seen any indication we will slow down,” adding, “D.E.I. is part of our DNA. It’s nothing we can just stop. We have a duty to tell the truth and make sure people coming to our spaces walk away with something they didn’t know before.” The Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit’s co-director and chief operating officer Marie Madison-Patton, likewise, called DEIA “part of our core values.”

To be fair, those small institutions receive little federal funding. Similarly an institution at the other end of the spectrum, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, whose director, Max Hollein, said in a recent interview with the French newspaper Le Monde that the museum is supported well enough that Trump’s anti-DEIA actions “do not apply to us, and we are not making any changes to our exhibitions or programs.”

In Los Angeles, however, the Japanese American National Museum (JANM), a Smithsonian affiliate, took a stand against the administration’s DEIA orders that will have a considerable cost attached. While many government entities, including the Pentagon, have been ordered to scrub anything that could be construed as supporting DEIA efforts from their websites, board chairman Bill Fujioka told the Los Angeles Times that the museum would “scrub nothing.” For this act of resistance, the museum stands to lose some $1.4 million in federal funding, or about 10 percent of its budget. In the short term, private funders have come through to meet the shortfall.

Ann Burroughs, board chair at the Japanese American National Museum. Courtesy JANM.

“We’re not going to change our history,” said board chair Ann Burroughs in a video call. “We’re not going to trade our values. In 1942, when Japanese Americans were incarcerated, almost nobody stood up for them. That’s why JANM has to stand up for other museums.” The museum would be interested in participating in any class action legal action against the Trump administration, if one is initiated, she said.

Burroughs served time as a political prisoner in South Africa for protesting apartheid. That experience, she said, “certainly gives me a pretty deep understanding of what can happen when public policy and government policy is shaped and determined by racism and by fear. I understand all too well what can happen to society when that fear becomes choking.”

Where Will Help Come From?

“Nobody’s coming to save us,” said the Parrish Museum’s Ramirez-Montagut. Many experts interviewed for this article speculated about what major, well-endowed public and private museums could offer in terms of leadership. One, speaking off the record about institutions like Columbia University, wondered, “What’s the use of having ‘fuck you’ money if you never say ‘fuck you’?”

Los Angeles arts writer Carolina Miranda, in the April 8 issue of her KCRW newsletter, called on one such institution, saying, “Now would be a good time for the Getty (which, as of 2023, had an endowment of $8.6 billion) and its partner institutions to gather with local arts organizations large and small to see how they can support each other in the coming months and years.”

A spokesperson for the Getty said the institution is responding to a rapidly changing regulatory landscape, like all arts organizations. “Getty has always partnered with local arts organizations as a matter of course and especially during crises, and we have worked steadily over decades to build significant networks and to support them,” a spokesperson said in a statement. “We will continue our work in support of the visual arts in our collections, in our communities, and with our partners.”

The Getty Center in Los Angeles, California. Photo: David McNew / Getty Images.

Where will museums get funding to replace the cuts? Not every museum can likely replicate JANM’s success, and even Burroughs realizes that a surge in support may not be sustainable in the long term.

Egan said museums may be able to turn to philanthropic foundations, pointing out Boston’s Barr Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation as potential supporters. “Barr is holding steadfast to all of its commitments, including in the arts,” said Barr’s president, Jim Canales, in an email. “We’re also in close conversation with our museum and other arts and creativity grantees to understand how these changes are impacting them, and what flexibility and support they need most at this time.” The Mellon Foundation published a letter from president Elizabeth Alexander decrying “threats” to organizations like NEH and ILMS, and saying that “Mellon is a resolute champion of the arts and humanities, of museums and libraries.”

All the same, because of the administration’s rapacious taking of money from other public support programs, those foundations may be under that much more pressure.

Museums could also look to private and corporate funders for support, but, Egan pointed out, that can cut two ways. Some “may be sensitive to being aligned with an institution that is outspoken on issues like DEI,” he said, but on the other hand, “there will be foundations, individuals, and even corporations who want to align themselves with leadership that speaks in opposition to what’s taking place. There is a buyer today for that museum in most American geographies.”

Without questioning the challenge of the current climate, Egan said, he does see a potential upside in the visibility the Trump administration’s acts have brought to museums and to the “alphabet-soup” agencies (those known by acronyms like NEA, NEH, and IMLS) that have long supported them.

“Part of me is optimistic that the American museum has the opportunity to express a heightened and even more central role in the national discourse than it possibly could have dreamed of three months ago,” he said. “For the first time in decades, arts and culture has entered into the discourse about the future of American democracy with a level of consistency and of electricity that demands the attention of not just arts people but the American public more generally.”