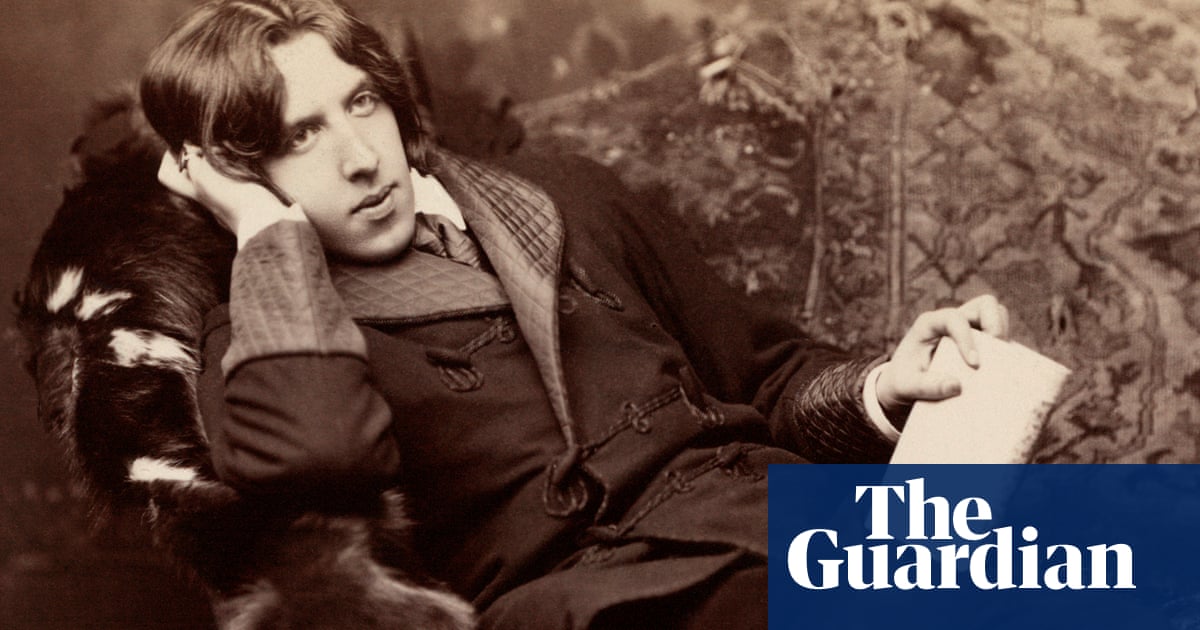

Oscar Wilde thought hard work “the refuge” of those with nothing better to do while he envisaged a society of “cultivated leisure” as machines performed the necessary and unpleasant tasks.

Karl Marx’s dream was of state-regulated general production that allowed liberated workers to “hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner” without the drudgery of being tied to one job.

The 19th-century socialist activist William Morris advocated for more pleasurable work, believing that once the profit motive of the factory had been abolished, less necessary labour would led to a four-hour day.

So Elon Musk’s suggestion to Rishi Sunak that society could reach a point where “no job is needed” and “you can do a job if you want a job … but the AI will do everything” revives a debate on the issue of how we work that has long been discussed.

Yet a world without work, experts question, may be more dystopian than utopian.

“This is an old, old story that never actually happens,” said Tom Hodgkinson, co-founder of the Idler magazine, which for three decades has been a platform to examine issues surrounding work and leisure.

“There was a poem in ancient Greece saying, ‘Isn’t it wonderful that we have invented the watermill so that we no longer have to grind our corn? The women can sit around doing nothing all day from now on.’ It’s that kind of recurrent idea.

“People like Bertrand Russell were talking about this in the 30s. What would we do without work? One view is people wouldn’t know what to do because people are more or less slavish. That they would just sit around watching daytime TV or porn all day.”

In fact, given more free time, such as on furlough during Covid, “they start living better”, Hodgkinson said. “They are starting neighbourhood groups, doing more gardening, doing up the house, spending more time with family, doing creative things, playing music, writing poetry, all the things that are part of what I would call a good life.”

Despite that, he said, studies had shown that paid work was beneficial for mental health, for status and identity.

“I think we need to do some sort of work. We should be moving towards a shorter working week, and more leisure-filled society,” Hodgkinson said, adding that a radical overhaul of our economic and education models would be needed to eliminate work on the scale that Musk predicted.

One significant body of research in 2019, led by Brendan Burchell, professor in social sciences and a former president of Magdalene College, Cambridge, established that eight hours of paid employment a week was optimal in terms of benefit in mental health, and that no extra benefit was subsequently accrued.

Setting aside the “awful jobs that really screw you up”, Burchell said, “your average job is good for you” in terms of social interaction, working collectively, giving structure and sense of identity.

A world without work “is a terrible idea of what society would look like for all sorts of reasons, as well as people’s mental health”, he said.

The labour market, as a way of distributing money around the economy, would have to be transformed, as would the education system, “to teach people how to fill their days, by writing poetry or going fishing or whatever, instead of going to the factory or the office”, Burchell continued.

Shifting to shorter working hours was shown to have “massive benefits for people”, said Burchell, but he added: “If we move to a society where lots of people are completely excluded from the labour market, then I get very worried that’s going to be a very dystopian future.”

In his book Making Light Work: An End to Toil in the 21st Century, David Spencer, professor of economics at the University of Leeds, also makes the case for less work, but not its elimination. “It would leave us bereft potentially of things that we value in work,” he said, citing communal enterprise, personal relationships and the development of skillsets.

So in essence, we would be a poorer, sadder, less skilled society. “Yes, there will be some loss through loss of work,” Spencer said. “I realise not all work is good. So we ought to automate drudgery, seek to use AI to reduce the pain of work, and therefore leave work which is good.”

He draws from Morris, who talked about bringing joy to work. “Skilful work is good work and it has a role in the creation of a better society,” said Spencer. “We ought to use technology to create less and better work. In that sense, the future can be really positive.

This was, he added, the future imagined by “Oscar Wilde, William Morris, and a lot of utopian positive thinking, where technology makes work lighter. It’s not eliminating work – it’s bringing light to work.”