Erin Coughlan de Perez was living in New York City when Hurricane Sandy struck in 2012.

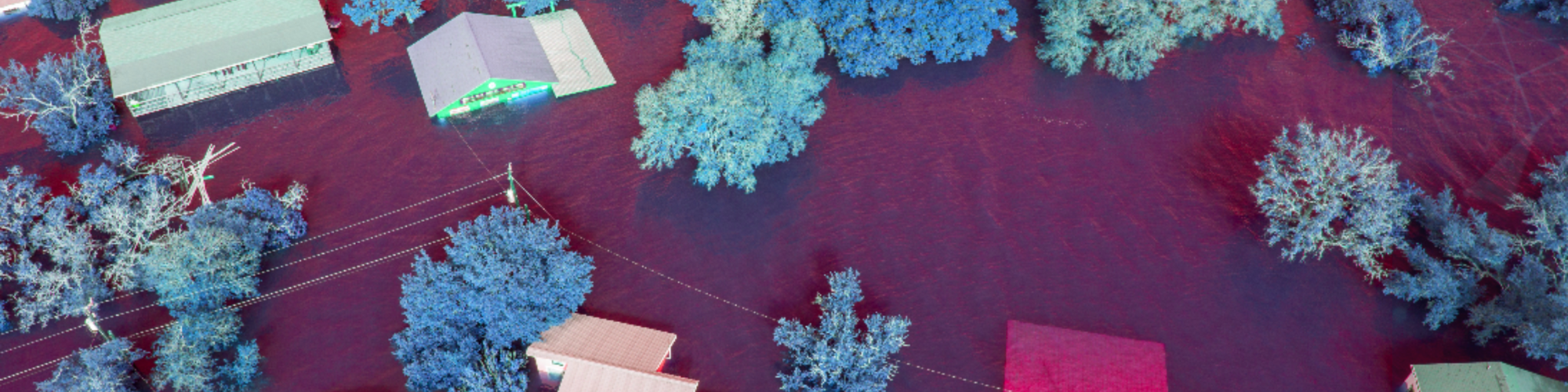

One of the largest storms ever to hit the city, Sandy killed 44 residents, displaced thousands, and caused billions of dollars in damage. “To be a part of the community and to see what went well and what didn’t—that had an effect on me,” Coughlan de Perez says.

Now a research director and the Dignitas Professor at the Feinstein International Center at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University, Coughlan de Perez is leading an international, interdisciplinary team of researchers in identifying methods to prevent negative health outcomes after climate-related disasters like floods, typhoons, and droughts.

The group, Center for Climate and Health glObal Research on Disasters (CORD), includes more than 25 named researchers and 10 doctoral students spread across seven universities in the United States, Bangladesh, Lesotho, Namibia, Mozambique, the Philippines, and Uganda.

CORD recently received a $3 million grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Over the course of three years, researchers will use the grant to analyze vast amounts of data and identify pragmatic steps that can be taken ahead of predicted hazards to reduce, or ideally prevent, dangerous health outcomes for particular communities affected by environmental catastrophes.

The hope is ultimately to help put in place protocols that will head off occurrences of cholera, malnutrition, and diseases like dengue.

“Part of the idea behind this grant, and what makes it so exciting,” Coughlan de Perez says, “is that we’re not just studying how bad climate change is. The point is not to write more studies saying sea levels are rising or floods are devastating. It’s to help future-proof health against climate catastrophe.”

Tufts Now sat down with Coughlan de Perez to find out more about how her group will identify anticipatory actions, what role data will play, and how the findings might help prevent human health disasters.

Tufts Now: What exactly does it mean to future-proof health against climate catastrophe?

Erin Coughlan de Perez: It means anticipating specific disasters in specific places and breaking the link between those disasters and harmful human health outcomes.

Climate catastrophes are terrible, and they vary around the world, both in the shapes they take and in the outcomes they lead to. Initially, we’re going to look at six case studies, each led by researchers at one of the collaborating universities. Our aim is to build three different methodological approaches.

The first case study looks at cholera and other diarrheal diseases in refugee populations in Uganda. Floods and other climate-related hazards have large impacts on these refugee populations, because they are often living in hazard-prone areas and have less access to services. We want to investigate how floods might affect health in refugee populations differently, and what might need to be done differently to prepare for them and avoid negative health impacts.

The second looks at maternal and fetal health in Bangladesh. With rising oceans, water sources there are becoming salty, and that’s having terrible impacts, especially on pregnant women.

Then, two universities in southern Africa are researching the links between drought and food insecurity, malnutrition, and mental health. The mental health aspect in particular is under-researched. We want to investigate what it means to be living through climate-related crises that just don’t seem to stop—how do people cope?

And, finally, we have case studies examining cholera in Mozambique and dengue in the Philippines, both induced by cyclones.

It is, of course, extremely important that we continue taking steps to stop climate change, including reducing emissions and using green energy.

But this project is not focused on controlling or stopping climate disasters. We already live in a changed climate, and things are going to get worse. What we need to know is how we can survive and thrive in this changed climate, especially for under-served and at-risk communities globally. How do we manage the current situation and the situation 20 years from now? What choices can reduce outbreaks and snap the link between storms and human health outcomes?

Read More