Kelly Xi became an artist by chance. As an undergraduate, her focus was initially on molecular biology. But a scheduling conflict landed her in a Photoshop class instead of the molecular genetics class she’d intended to take, and her life course was forever changed. “From that first interface I was like, ‘Oh I could do this,’” Xi said. “I was so opened up to the possibilities of being expressive and bold and taking creative risks but also, like, finding your voice.”

Through that class she met an alum of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), where Xi later attended grad school, earning a degree in art and technology studies in 2023. She then got hired as a nontenure-track (NTT) faculty member at the school, teaching a range of courses in the art and technology and contemporary practices departments, as well as in the school’s low-residency MFA program. Xi was the sort of engaged faculty member you always hope to have as a teacher—one who works with student groups, attends on-campus events, and does studio visits.

But Xi’s work came to an abrupt halt in December when SAIC provost Martin Berger sent her an email notifying her that the institution was putting her on paid administrative leave and temporarily banning her from campus for “misuse of SAIC resources,” according to emails that Xi shared with the Reader. Yet the reasons alleged seem to fall short of the sort of egregious acts that such severe sanctions would warrant, according to the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), which sets the standards for academic freedom and due process. The administration has accused her of sharing student email addresses with other students, printing for personal use, attempting to disrupt a career fair, and distributing external materials without authorization—ostensibly related to Xi’s work as a member of Art Institute of Chicago Workers United (AICWU), the union that represents the school’s faculty.

(In a statement, an SAIC spokesperson said it is their practice not to comment on personnel matters.)

Instead, the timeline of the school’s surveillance of and investigation into Xi’s activities, which date back to the student-led pro-Palestinian encampment staged at the Art Institute of Chicago last May, suggest the professor may have been targeted for political reasons. Across the country, waves of students and faculty at higher ed institutions are being disciplined for their speech—either at the hands of the nativist Trump administration or directly from their school leadership, seemingly emboldened by the rightward political tide or trying to get ahead of censure by the federal government. At SAIC, Xi’s dismissal seems to be part of an institutional move toward controlling communications and quelling political activity, moves that have included investigating students and limiting their ability to protest or share resources.

“Clearly these tactics are being used to intimidate really engaged people in our school,” one tenured professor, who asked to remain anonymous out of fear of retaliation, told the Reader. “I feel like they’re intentionally targeting specific students and specific faculty, maybe the most vulnerable ones, as examples.”

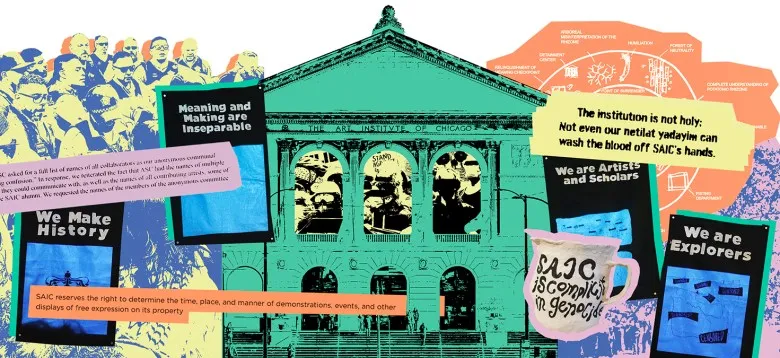

On May 4, 2024, a group of a few dozen students and organizers took over the manicured North Garden at the Art Institute of Chicago to resist the school’s complicity in Israel’s genocide in Gaza. (At the time, Israel had killed over 36,000 Palestinians following the October 7, 2023, Hamas attack; the death toll has since risen to more than 53,000 Palestinians.) Protesters set up tents and a sign reading “Hind’s Garden,” in honor of six-year-old Palestinian girl Hind Rajab who was killed by Israeli armed forces in early 2024. According to the People’s Art Institute and Students for the Liberation of Palestine—the coalitions behind the encampment—organizers were calling on the school and the museum to disclose all funding and investments; provide amnesty for pro-Palestinian faculty, students, and staff; and divest from any entities supporting Palestinian occupation, including cutting ties with the Crown family. Ranked by Forbes as the 30th richest family in the U.S., the Crowns are partial owners of the weapons contractor General Dynamics and are deeply embedded in the Art Institute. They’re significant donors—including funding a $2 million endowed professorship in the school’s painting and drawing department. Local artist Paula Crown received her MFA from SAIC in 2012; A. Steven Crown sits on the boards of both SAIC and the Art Institute.

Credit: Amber Huff

The encampment did not last long. The museum alerted the Chicago Police Department to the protest—which grew to encompass a few hundred people over the course of the day—within its first hour. According to the People’s Art Institute Instagram, while organizers were involved in a discussion with Berger over potentially moving the location of the encampment, the institution abruptly changed course and the museum asked CPD “to remove those illegally occupying the property.” A previous statement from the museum to the Reader states, in part: “After approximately five hours, an agreement could not be reached. The museum requested that the Chicago Police Department end the protest in the safest way possible, and arrests were made after protesters were given many opportunities to leave.” Demonstrators had occupied the garden and surrounding areas for just a handful of hours before police began forcefully clearing it, arresting nearly 70 people, most of them students. Similar encampments at other schools in the Chicago area had more longevity: One at Northwestern lasted five days, University of Chicago’s lasted eight, and another at DePaul stood for 17 days.

Xi was part of a group of faculty supporting the student protesters in the lead-up to the demonstration and during the negotiations with the school during the encampment, so her political activities were visible to SAIC’s administration by at least the start of May. What Xi didn’t know was that, even before the encampment, the school had already begun surveilling what she was printing on campus.

Throughout the spring, summer, and fall, Xi continued to publicly speak out and organize with AICWU’s contract committee—legally protected union activities. She also continued working with student groups—both SAIC-sanctioned and unofficial ones—which aligned with both her art practice and her courses. In February 2025, the Illinois conference of the AAUP, a branch of the national organization, filed a letter urging SAIC president Jiseon Lee Isbara and the rest of the leadership to reinstate Xi. The AAUP’s guidelines on academic freedom and due process are enshrined in most reputable school policies across the country, which adopt them of their own volition. While the AAUP has no power to sanction schools who fail to follow these policies, the organization can launch investigations and can place offending institutions on its official censure list.

The AAUP academic freedom and tenure committee wrote that, in the fall of 2024, Xi was teaching a course that incorporated “political activism as an element of the anti-racist curriculum she was hired to teach.” Thus, they continue, “It is hardly surprising that a faculty member whose work focuses on social justice and activism would engage regularly with student groups that focus on these very issues. It would be irresponsible for an artist scholar specializing in social justice and activism not to support students raising concerns about the situation in Gaza, about a faculty contract, and other matters of the day.” Xi’s printed materials for class were often political in nature; she also concedes that she sometimes printed items at the request of student groups, a practice that other faculty members the Reader spoke with described as routine.

Xi stopped printing completely in late October, after being told by a colleague that the administration was tracking large print jobs.

In the summer and fall, Xi was involved in Curators Under Censorship, the collective who organized an exhibition at the school’s student-run SITE gallery called “School as a Function of Empire.” The group began working on the show over the summer of 2024. Many of the organizers had been arrested during the May encampment and the show was in part a response to the police violence they experienced. One artist included the pants they had been wearing that day when they were dragged across the grass by police. Other works focused on the genocide in Gaza or the school’s ties to Israel, particularly its relationship to the Crown family.

From the start, organizers told me, the exhibition proposal received an inordinate amount of scrutiny from the school. “The students overlooking the curatorial SITE team were very receptive and were very supportive of us immediately,” Joey Maben, one of the show’s undergraduate organizers, told me. “But then the Art School Considerations [ASC] board, which is made up of administration, had a lot of questions for us, if I can put it that way.”

Another exhibition organizer, grad student Mira Simonton-Chao, said typically only the SITE team reviews proposals, whereas here every detail had to be submitted and approved by ASC. “With us, they were like, ‘You need to submit every single bit of information that you want to have present in the room, including any written material, for approval before we allow you to even go forward with planning.’ . . . We had a reading nook as well. They made us submit every single title that we wanted to have.”

The most pushback from ASC was in relation to the works submitted and who could involve themselves in the show, details that attorney Rima Kapitan, who worked with the curatorial team, confirmed to Sixty Inches From Center. Curators Under Censorship is an anonymous collective—save for a few representatives who met with ASC—that includes students, faculty, and alumni. According to organizers, ASC initially tried to say that the involvement of those who weren’t current students wasn’t allowed, although this stipulation hadn’t applied to previous SITE shows. ASC also had issues with the collective operating anonymously; they insisted on reviewing the names of every artist and curatorial member. So, although Xi’s pieces weren’t labeled as such in the show, ASC, and by extension school administration, were aware of her involvement.

Xi said this resistance from the administration made her suspect that she might be falling under the school’s scrutiny. Her desire to be a part of the show anonymously was the first time she’d felt the need to self-censor. “I had a suspicion that they weren’t going to be OK with me, a faculty member and employee, being involved in the show and showing artwork in the show . . . because it was directly about General Dynamics and the Crowns and problematizing our educational model at SAIC where we’re just not allowed to talk about these things,” she said. “I had a suspicion that was going to be an issue, especially because the dean of faculty is on the Art School Considerations board and John Pack [the head of campus security],” she said.

So began a monthslong back-and-forth between the collective and ASC, with the collective eventually enlisting Kapitan to assist them in navigating what they saw as undue censorship. According to SAIC’s Student Handbook, ASC “is designed to help students realize projects that may present health, safety, legal, or other challenges to the artist and/or members of the SAIC community.” Students and alumni I spoke with described ASC as usually getting involved in exhibitions or projects that pose a potential health or safety threat: working with weapons, an open flame, or biomatter. The handbook outlines these in a checklist, as well as the more ambiguous “potentially-sensitive content,” defined as “work which may reasonably be foreseen to result in a strong level of emotional distress or perception of threat in the viewing audience generally or in individual member(s) of an audience.”

Eventually, the ASC board rejected the curators’ proposal to have a community wall where the public could leave thoughts—a common strategy for engaging an exhibition’s visitors. “We didn’t want it to be like a traditional gallery where it’s like you’re separated from art and the artist as a viewer. We wanted to emphasize the community aspect, just given the subject matter,” Maben said. The collective put together community guidelines to make sure nothing hateful was written. “But even then the Art School Considerations board was adamant that that not be included.”

“They were saying the legal risk of it creating a hostile campus environment were too high,” Simonton-Chao said. “They just keep being like, ‘We just are worried about you guys getting sued, like, we’re not worried about us getting sued.’ . . . It was very framed in this way of trying to scare undergrads into self-censorship.” Simonton-Chao and Maben both lamented the opacity of ASC. Its members are not listed online and much of its purview seems subjective. “You can’t contest Art School Considerations because they give us no transparency of protocol or policy. They’re very authoritarian,” Simonton-Chao said. In the end, the collective compromised by having preapproved printed materials that visitors could wheatpaste onto the wall.

The board also stipulated that the gallery’s external-facing windows had to be covered so no one could see in and that security had to be present at the opening. The bureaucratic hurdles resulted in delayed installation and an inability for the organizers to promote the show as much as they would have liked. Nevertheless, the show drew a large crowd. An article from SAIC’s student-run F Newsmagazine shows a line of visitors outside the gallery waiting to get in on opening night. “The show came out very beautifully,” Maben said, noting that there were no issues and no reports of anyone taking offense to its content.

The extra attention to the “School as a Function of Empire” exhibition is of a piece with other changes at the school that seem intended to control speech and organizing generally. Last fall, a new demonstration policy for students was announced, designating just one area on campus open to protests: the “280 pit,” an outdoor space—which is not fully wheelchair accessible—in front of SAIC’s 280 S. Columbus building. The policy requires students request the use of the area at least three business days before the planned event. “SAIC reserves the right to determine the time, place, and manner of demonstrations, events, and other displays of free expression,” the policy states. It goes on to detail vague consequences of violations of the policy, noting that “each case is context specific.”

Credit: Amber Huff

When SAIC’s student government account shared the new policy on its Instagram, student responses were overwhelmingly incredulous. “Thank you for throwing us this bone and allowing us a space to protest your contribution to genocide on your terms !!! because every revolution begins on the terms of the oppressor!!” read one response. “This is actually crazy coming from a school who actively teach [sic] us to use our voice & speak out and act on important issues. The fuck kind of artists are we for staying silent????” read another.

The school also has a strict policy on pamphleteering, forbidding “solicitation and distribution of non-AIC sanctioned materials on or at its premises by any student, employee, or non-employee. . . . Students may not solicit or distribute materials for any purpose at any time on AIC/SAIC property.” In an email replying to our request for comment, an SAIC spokesperson said that the school’s “solicitation policy has been in place for many years.”

“It’s an art school. It doesn’t make any sense,” Xi said of the policy. “Things like zines and posters are included among the solicitation policy now.” It doesn’t seem to take into consideration the fact that zines, Xerox art, and other printed matter are often part of courses as well as faculty and students’ art practices. Indeed, the school’s library has a zine collection and a zine group.

A new, reduced print budget for faculty—which was implemented at the start of this year, after Xi’s dismissal—also poses challenges in the way professors plan their classes. Two professors said their printing allotment used to be unlimited; now it’s capped at $25. If they want to print more, they need to ask their department heads for advance approval. “It’s quite annoying because . . . there’s like five pages of mandatory things that we have to put in [printed syllabi],” said lecturer Sarah Bastress. “I maxed out my printing on the first day without printing a syllabus for every student. . . . It is a really blatant, silly thing for them to do, just to save face for punishing Kelly.”

The new policy has forced her to change her teaching practice. “I used to print a schedule for every class for students and I used to print poems,” she said. “It’s very frustrating.”

“Print costs have gone up so much, and our budgets have stayed the same,” the tenured professor told me. “So it gets spent really quickly.”

The solicitation policy and the print policy appear to be directly related to Xi’s dismissal. One of the charges that Berger levied against her was “unauthorized distribution of external materials,” which seems to refer to protected union activities. Xi, along with other AICWU members, would regularly pass out union stickers, buttons, and fliers, and would meet with colleagues on campus to have them sign union or strike pledge cards or talk about union business. Labor law protects employees engaged in union activity, from circulating petitions and talking with coworkers about working conditions to protesting and distributing union literature and insignia.

Credit: Shira Friedman-Parks

In fact, Xi was particularly active in on-campus union organizing in the days leading up to her removal. She first realized something was off on November 19, 2024, when she noticed her faculty profile and two promotional articles about her work as a grad student had been removed from SAIC’s website. That same day, her faculty ID card was blocked from printing anything. She reached out to her department chair, who told her that Berger had reached out to him directly to say that Xi was under investigation. Later that day, Xi was asked to meet with Berger. Berger relayed over the phone to AICWU’s AFSCME union negotiator, Kathy Steichen, that the meeting would not be disciplinary and thus Xi would not be allowed to have a union steward present. (AICWU is affiliated with AFSCME Council 31.) The Supreme Court case NLRB v. J. Weingarten, Inc. stipulates that employees have the right to union representation during investigatory interviews.

“But it became disciplinary,” Xi said. “It became immediately clear. You know, if my contract was on hold, that is by definition disciplinary.” At the November meeting, Berger told Xi she was under investigation by executive director of campus security John Pack, who was looking into her allegedly nonacademic printing and alleged involvement in a student’s attempt to disrupt an on-campus career fair. (A student tried to make an announcement over the microphone and asked Xi to film them. But they were unable to access the sound system, and ultimately, no disruption occurred.) Berger informed Xi her spring classes were on hold until the conclusion of the investigation.

The next day, Xi met with Pack, associate director of security Dennis Leaks, and Steichen, the AFSCME negotiator. There, Pack presented Xi with a list of everything she had printed from May 3 to October 28 as well as surveillance footage of her printing. As the AAUP support letter states: “Among the items in the folder that Mr. Pack claimed to be illegitimate/non-educational include: zines on gentrification in the arts, history of organizing at SAIC (produced from an archive of activist faculty copy-printing), student org Teach-in flyers, and a student-made collage on student activism.” Xi told both Pack and her department head that she was willing to pay for the nonsanctioned printing and also asked to review the print jobs they had flagged but to no avail.

All the faculty members I spoke to for this article said that having administration track a colleague’s printing was unprecedented. “Hearing that John Pack was tracking Kelly’s copies for months is unbelievable,” the tenured professor wrote me over email. “We’re all guilty of making personal copies here and there.”

“One of the perks [of teaching at SAIC] is that you get to use the school resources,” said Mary Patten, an SAIC professor emeritus who has been at the school since 1993. “All faculty have access to resources at the school. Tech resources. You can use an editing room. You can check out a camera. You can use the photocopier and make Xerox art. . . . I’ve never even heard of a faculty getting disciplined for making copies of their own resume or something. Never. I mean, photocopying, that’s not one of the big budget items anyway in the school.”

In the days leading up to her dismissal, Xi continued with her regular teaching and union activities. On November 25 and 26, she and another AICWU member visited colleagues in their classes to talk to them about how bargaining was going. On December 3, after the Thanksgiving break, Xi spent much of the day meeting with other colleagues about the union and tabling with an AICWU colleague about the strike pledge and about a student petition that had just dropped in support of nontenure track faculty.

“NTT faculty are overworked, underpaid, and undervalued despite being the driving force behind all our cherished parts of SAIC. NTT faculty have supported us unconditionally, and SAIC exploits this devotion.”

The petition, called Student Solidarity with SAIC NTT Faculty, was published online on December 2 and also went out as a mass email to the student body. NTT faculty at that point had been negotiating their first contract with the university since June 2023 and were gearing up for a potential strike. “Your professors’ working conditions are your learning conditions,” the letter stated. “NTT faculty are overworked, underpaid, and undervalued despite being the driving force behind all our cherished parts of SAIC. NTT faculty have supported us unconditionally, and SAIC exploits this devotion. We must reciprocate the care that our faculty show us and echo their demands by supporting their strike preparations.” To date the petition has over 800 signatories online. (In the fall semester, the school had a total student body of 3,395.)

While it may seem innocuous for students to send out a mass email to their fellow classmates, the administration considered it “confidential student information.” The school quickly determined that Xi had a hand in providing students with a portion of that email list, and at 4:55 PM the following day, December 3, Xi received an email from Berger with the subject line “**URGENT**.”

“I’ve received a report that you appear to have ignored both our policies and my specific stated expectation that you be mindful not to use SAIC resources for anything other than work duties,” Berger wrote. “Specifically, it appears that you may have taken information you may have access to based on your employment, namely the contact information for the entire student body, and shared it with students for non-work reasons. If true, this would be an egregious violation.”

He went on to revoke her SAIC privileges, freezing her staff ID, banning her from both SAIC and the Art Institute premises, and putting her on paid administrative leave through the end of the fall semester.

Xi didn’t get a chance to say goodbye to her students. She was removed from her yearlong class with just two weeks left in the semester. On December 23, Pack forwarded Xi a letter from Berger explaining the result of the investigations. It found that she violated school rules, namely unauthorized distribution of materials, personal printing, and “inappropriate access to and circulation of confidential student information.” Berger relayed that her complete ban for SAIC and AIC properties would remain in place, as would her access to any SAIC resources, including her email.

“I can’t go to Gene Siskel. I can’t do studio visits with grad students who have asked me. I can’t attend any exhibition or event or talk,” Xi said. “It really prevents me from my ability to engage as an artist.” Xi, who often makes involved installations featuring neon, has used SAIC’s fabrication facilities since she was a grad student there. “My practice is kind of at this pivot point, hopefully not dead end.”

Xi eventually got in touch with the Illinois AAUP who sent their support letter to SAIC’s president on February 3, 2025. It drew from conversations with Xi and some of her colleagues as well as a grievance Xi attempted to file with SAIC. Xi spent two months compiling documentation for the grievance, soliciting support letters from a number of colleagues and gathering evidence.

But she didn’t hear back—because the school had blocked not only her SAIC email address but also her personal Gmail account from being able to communicate with anyone at SAIC. She didn’t realize that until she got an out-of-office email from Pack, in response to an email she had tried to send to a colleague. She submitted her materials again using a different email and was initially told by the new grievance committee chair, professor Lou Mallozzi, that there may be some part of her grievance that they could address. But a week later, after reviewing her complaint, Mallozzi wrote that the committee could not in fact take up her grievance. “According to the faculty handbook, the grievance committee’s purview regarding lecturers is very, very limited. In fact, the official policy is that the grievance procedure is open specifically to tenure track and adjunct faculty, with no provision for lecturers,” he wrote in an email.

Like many other schools, SAIC increasingly relies on lecturers and part-time faculty. As of last year, they made up more than 80 percent of the school’s faculty, 632 out of 783. Mallozzi’s email implies that the vast majority of SAIC’s teaching staff have no right to due process, though the faculty handbook, which he references, states no such thing. The handbook’s grievance section begins: “A faculty member, whether full- or part-time, may bring a grievance against the School for the reasons set forth in Section 7.1. A” which includes allegations of a policy violation that results in suspension.

The handbook does, however, include the AAUP’s guidelines on both academic freedom and due process. Those guidelines stipulate that a faculty member may be suspended “only if immediate harm to the faculty member or others is threatened by continuance.” “Based on the information we have available to us, Kelly Xi’s continued presence on the SAIC campus appears to pose no threat of ‘immediate harm’ to anyone,” wrote the AAUP committee in their support letter. They continued, “It appears as if SAIC is punishing Kelly Xi for her extramural speech and action. . . . Based on our current understanding of what has transpired, SAIC looks to be in violation of both AAUP Recommended Institutional Regulations concerning academic freedom and due process and provisions of its own handbook.” SAIC’s faculty handbook does mention that a grievance may be brought if a school entity contravenes the provisions of the handbook.

The school declined to respond substantively to AAUP’s letter because Xi was pursuing a grievance through the school and was working with a lawyer, and because personnel matters are confidential, according to Steve Macek, who chairs the Illinois AAUP committee. “I don’t think—especially administrations who behaved the way they have—usually want to be forthcoming with information,” Macek said. If they had, they could have easily sought Xi’s permission to discuss the case.

Macek said that AAUP has received a large influx in complaints in the past several months and, with limited resources, it cannot intervene in every situation. “What happened with Kelly seemed particularly egregious. That’s why we took the step we did of writing a letter,” he said, adding that the organization is seriously considering launching a full investigation of SAIC, which could result in an official censure.

AAUP regulations state that removing someone from the classroom is the most severe sort of penalty, and should be used only if there is an immediate threat. “That clearly was not . . . true in this case,” Macek told me. “Whatever problems they had with her providing printing privileges to the students or whatever the problems they had with her, it didn’t rise to the level that justified what they did. And it’s just outrageous to yank somebody out. It’s a disservice to their students—and it’s also a clear violation of the academic freedom of the professor.”

Patten told me, “Never in the history of the school has a person who’s been teaching been banned from campus. I mean, it’s just insane.”

“This increased climate of fear is something which is very, very real, and it’s very felt.”

“I think it’s really clear that the SAIC administration did this to silence Kelly and her outspoken activism in support of a free Palestine, her vocal support of the union, her involvement in getting other faculty to be excited about the union and to get involved,” NTT lecturer Anneli Goeller said. “She is not the only faculty member who has been a proud and supportive union member, or who is in support of a free Palestine, and who has been active in antigenocide campaigns. And so I came to that conclusion myself as well, that she is being targeted in part because she is a woman of color, involved in activism and vocal about it and unapologetic about it as she should be. I have been involved in similar campaigns throughout this whole time, and I have not had any discipline.”

Students and faculty I spoke to for this article described a subdued atmosphere on campus this semester. They attributed it to the federal government’s witch hunt of academics and students who have spoken out in support of Palestine and to the school’s dismissal of Xi and its investigations into student activists. “This increased climate of fear is something which is very, very real, and it’s very felt,” NTT lecturer Garrett Johnson said.

As for Xi, she filed an unfair labor practice charge with the National Labor Relations Board, though the prospects for that are uncertain, given cuts made by the Trump administration. The AAUP is still looking into her case. Xi is hopeful that one day the faculty handbook will be rewritten to more explicitly protect her former colleagues—something AICWU is actively seeking to get into their contract. Otherwise her future is uncertain.

“It’s been really difficult. It’s been kind of like a four-months grieving process,” she told me. “I put ten years, the last ten years of my life, towards . . . I feel real naive about the purpose of art. And I mean, it’s important that we don’t silence repression, but I also feel really exposed right now.” For now she’s taken a temporary job delivering compost. She doesn’t know if she’ll find another job in the education sector. “I know that sounds really grim, but that’s kind of what I’m seeing in our present reality, people being targeted for their political and intellectual beliefs.”

Her removal from the classroom is not only a loss for Xi, but also for the school and, more importantly, her students. “They are totally shooting themselves in the foot because they’re depriving students of this amazing faculty person who’s one of those exceptional faculty who just is so generous and so resourceful for students,” Patten said.

Bastress agreed. “Kelly did a wonderful job making some really talented students and idealistic students feel seen and like they had the ability to make a difference,” she said. “I don’t have a harder-working person in my mind than Kelly.”

That spark that Xi felt when she first started making art is still accessible, but maybe a little less so. You can hear it when she talks about teaching. “It’s what I try to make infectious for all my students,” Xi told me. “It’s incredible. You know, for me, empowering them, seeing the world through their eyes anew, every single semester.” She never imagined that supporting her students, helping them become politically engaged citizens and artists, would cause her to lose her job. “Opposing a genocide, I didn’t question that.”