The art world was poised to hear Koyo Kouoh reveal her vision for the 2026 Venice art biennale. But on May 10, just days before the presentation, word broke that the 57-year-old Cameroon-born curator had died of cancer — leaving those who knew her stunned and everyone else wondering what it meant for the world’s most significant exhibition, set to open in less than a year.

At a conference last Tuesday, a team of Kouoh’s advisers read the words she had written for the occasion and revealed her title for the event: In Minor Keys, a theme that invites us to listen to an alternative emotional register — one evoked by “the blues, the call-and-response, the morna, the second line, the lament, the allegory, the whisper”. Rejecting “orchestral bombast and goose-step military marches . . . the minor keys are small islands, worlds amid oceans with distinct and endlessly rich ecosystems, social lives that are articulated, for better and worse, within much larger political forms and ecological stakes.” In other words, Kouoh’s biennale will be grounded in the radical perspectives often sidelined within dominant political and ecological narratives: the artists exploring new possibilities on the periphery and humming quietly in the background will take centre stage.

The show will go on — with Kouoh’s plans delivered by the international team of curators, researchers and writers she was already working with: Gabe Beckhurst Feijoo, Marie Hélène Pereira, Rasha Salti, Siddhartha Mitter and Rory Tsapayi, and the many artists she had chosen to platform. This collaborative execution by people she knew or mentored will embody what many say is Kouoh’s defining contribution to art: developing a self-sustaining creative infrastructure to amplify and connect creative voices across Africa and its diaspora, as well as other communities across the world that have been previously been drowned out in the Eurocentric art world. Artist Yinka Shonibare, a member of the global council Kouoh put together when she took on the leadership of Cape Town’s Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in 2019, tells me: “She was a pioneer, but she didn’t just want to be the first — she wanted to bring people along with her.”

Oluremi C Onabanjo, curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, sees herself as one of those: “Koyo expanded a sense of possibility for a generation of African curators across the globe, encouraging us to centre artists and community in all that we do,” she says. Curator and artist Gabi Ngcobo, who sat on the Zeitz advisory board with Kouoh before she took on her leadership role there, agrees: “She opened doors we didn’t think possible to open. We will remember her for the spaces she carved for artists from Africa and the diaspora and many will continue where she left off.”

Kouoh’s own perspective was slightly different, says her friend, the artist Julie Mehretu. “She was a leader, but she didn’t see herself that way — she thought of herself as being immersed in the mix, a participant intertwined inside a constellation of curators, artists, writers, thinkers, and everyone mobilising together as a collective.”

She saw institution-building as crucial to her curatorial practice. Her pan-African conviction — “I belong to the entire continent, and the entire continent belongs to me” — fuelled projects such as Raw Material Company, the Dakar arts centre she founded in 2008 after moving to Senegal from Switzerland, where she mostly grew up. It is a space designed to empower emerging curators, foster critical thinking and build local and international connections, through exhibitions, publications, symposia and residencies. Since then, curators and artists have passed through and remained in its orbit as advisers and supporters — including Pereira of her Venice curatorial team.

All of this makes for strong foundations that remain in her absence. “Raw is not going anywhere because it doesn’t depend on one person,” says Fatima Bintou Rassoul Sy, its director of programmes. “We’re going to maintain the space and create a transition that is smooth enough so people don’t feel that there is a gap.”

Similarly, her rescue mission at Cape Town’s Zeitz MOCAA rebuilt an institution reeling from scandal. After founding director Mark Coetzee resigned amid allegations of misconduct, Kouoh put herself forward for the role, despite having no ambitions to be a museum director, seeing it as the responsibility of cultural workers to ensure that this contemporary art institution for Africa did not fail. Storm Janse van Rensburg, who worked with her there as senior curator for five years, recalls: “Koyo was handed a magnificent piece of architecture, which had to be reverse engineered into a museum and institution.” In pulling this off, she navigated funding crises, a pandemic, fraught community relations, low staff morale and being a Black female leader in a South Africa still divided along racial lines. Against these odds, Janse van Rensburg says, she revitalised the programme and reimagined the museum.

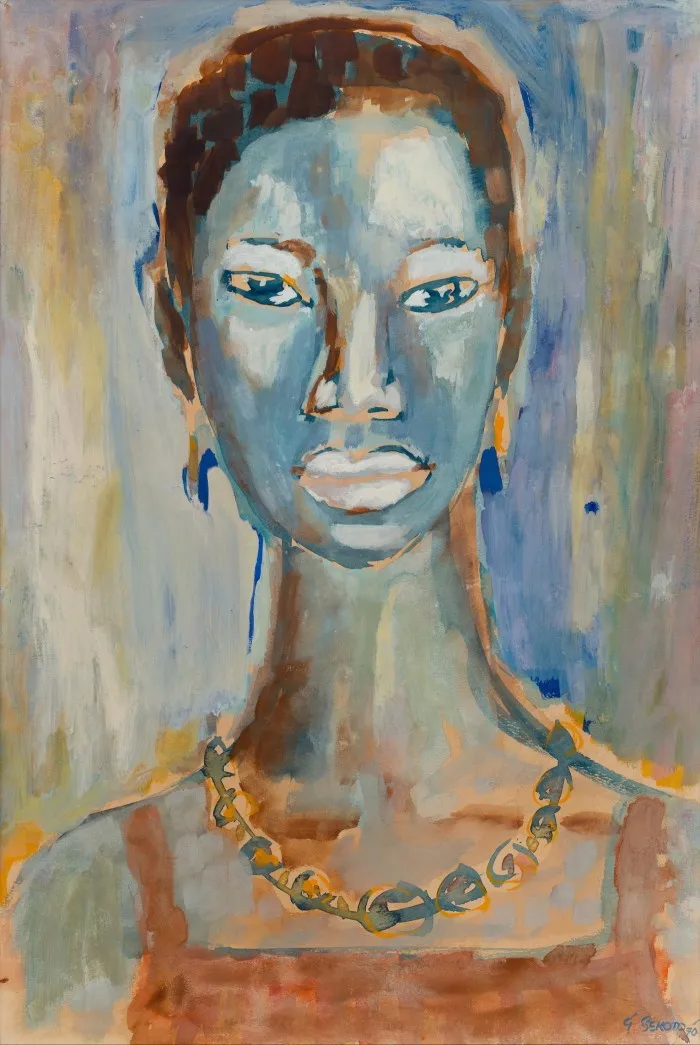

Yinka Shonibare points in particular to Kouoh’s introduction of solo retrospectives of female artists such as Tracey Rose and Mary Evans, as well as the touring group show When We See Us: A Century of Black Figuration in Painting, as landmarks. She brought the institution “back to life again”, he says.

When she was appointed in 2024, Kouoh became the first African woman to curate the Venice art biennale in its 130-year history — a significant label, but also one that carries disproportionate weight. Lesley Lokko knows this feeling all too well: in 2023 she was the first person of African descent to curate the architecture biennale. “For most Africans, the prefix ‘first’ shadows you like a curse,” she says. The ambition, she says, is to be “the second, third, fourth, until it’s no longer a USP, simply part and parcel of what a curator does, irrespective of where they’re from.” African curators are, she reminds us, “as diverse and divergent and eclectic as anyone else”.

Kouoh embodied this eclecticism: intellectually rigorous yet boundary-defying, she focused less on categories and identities or trying to prove anything, than on people, for whom she had boundless enthusiasm. “It was never about fulfilling some grand vision for herself — she really was in service of whatever artists wanted to do,” says Mehretu.

Her optimistic view of a new world ready to be born out of crises feels prescient now that she’s gone. “Though often lost in the anxious cacophony of the present chaos raging through the world, the music continues,” she wrote, “the other worlds that artists make, the intimate and convivial universes that refresh and sustain, even in terrible times; indeed, especially in terrible times.”