In 1947, when MoMA celebrated Ben Shahn with a massive retrospective, curators, critics and fellow artists concurred in naming him one of the 10 greatest painters in the US. But his rocket-like career was on the way up and down at the same time.

Shahn’s paintings of doomed revolutionaries, photographs of stoic Depression-era farmers, and posters of unionising workers had made him a blue-collar hero as well as a celebrity on Manhattan’s vernissage circuit. He and Willem de Kooning represented the US at the 1954 Venice Biennale.

But those were also ominous years for a staunchly political artist. The FBI placed him under surveillance, CBS added his name to a blacklist, and, in 1959, he was summoned to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Shahn received similarly chilly treatment from the collectors and ideologues of abstract expressionism, who had zero interest in grand polemics or figurative art for the masses. He became increasingly marginalised, his slow fade-out only briefly interrupted by the raft of obituaries and posthumous praise that appeared on his death in 1969.

By the 1990s, his reputation was so degraded that the critic Robert Hughes, in his celebrated history American Visions, dismissed him with a contemptuous assessment that verged on antisemitic. “Shahn painted the American working class as a bunch of unhappy yeshiva students in blue collars,” he wrote. “His workers looked as if three of them together couldn’t have lifted one of the sledgehammers that Benton’s eupeptic Kansas railroad mechanics tossed around like jackstraws.”

At last, Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity, a lively and essential exhibition at New York’s Jewish Museum, rediscovers what several generations of lefties, workers and egalitarian connoisseurs already knew: Shahn was a master at combining political passion, emotional resonance and rhetorical precision into a sharp, activist art. He now seems more relevant than ever.

Shahn was born in 1898, in Kaunas (Kovno), then part of the Russian empire and now in Lithuania. He came by his sense of injustice early: after his father was sent to Siberia for anti-tsarist activity, the rest of the family moved to New York in 1906. (The father escaped and joined them later.)

The exhibition opens with the young Shahn’s first great series, “The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti”. Like so many others, he saw the arrest, trial and execution of the two Italian anarchists as a bigoted attack on the poor and foreign-born, Catholics, and all those who demanded fairness. But he resisted tragic hysteria, instead representing the events in flattened forms, punchy lines, and a deadpan manner reminiscent of George Grosz, another artist outraged by disparities of wealth and power.

The series culminates with the grey-faced anarchists lying in their coffins. Three wise men — a retired judge and two university presidents who reviewed the case and reaffirmed the sentence — stand over the bodies like expensively dressed undertakers or human vultures, waiting for carrion. Their expressions of grim disdain reflects Shahn’s opinion of the judges even more clearly than theirs of the deceased.

When this large canvas was shown at MoMA in 1932, it provoked the ire of some trustees, who saw themselves in the trio of ghastly grandees. The controversy gave Shahn his first direct experience of class warfare. He found it invigorating.

The Great Depression cemented his political commitment. He dedicated his art to labour, sympathised with sufferers at home, and protested against the rise of fascism abroad. Though he was sympathetic to communism, his independent temperament kept him from joining the party.

In the 1930s, Shahn adopted the camera, brandishing it as both a tool of change and an instrument of surreal nostalgia. He hauled the thing to boyhood haunts that now seemed haunted in a different way: a Lower East Side kosher butcher where cow hooves and stray mammal limbs dangle grotesquely in the window; another that resembles an empty theatre, with a single hunk of something dubious and bloody at centre stage. A woman leans wearily against the doorway, lost in reverie while her store’s paltry contents rot.

Shahn headed for the dust bowl for President Roosevelt’s Resettlement Administration (later renamed the Farm Security Administration) to document a heartland ravaged by drought and, like Dorothea Lange, he found dignity in deprivation. Some of the portraits he shot in Arkansas eventually served as the infrastructure for more stylised paintings, in which one farmer’s misery became an emblem of collective pain.

“Sam Nichols, Tenant Farmer” (1935) is a rocklike presence in a world of impermanence, his shirt so threadbare it barely holds together, the shack at his shoulders threatening to collapse. His hand covers his mouth and chin in a gesture that could be pensive or anguished.

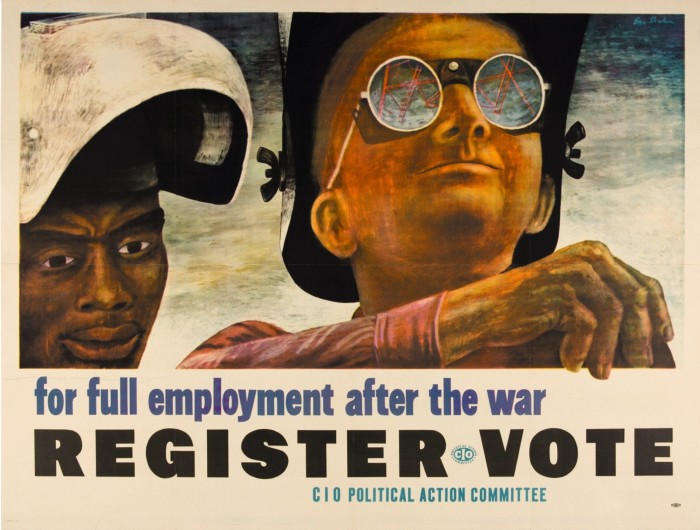

Shahn later pressed the same figure into service as a labour camp inmate in the canvas “1943 AD”. The hand, now grown into a giant’s paw, possesses a gnarled power, as if it were about to tear away the barbed wire that separates him from the viewer. Hands, stony and oversized, play a central role in Shahn’s imagery, often expressing the virtues of manual work and the intensity of political struggle. In a 1946 voter registration poster designed for a federation of unions, Shahn recycles his picture of Nichols once again, this time emphasising the contrast between ready hand (once again covering the mouth) and sorrowful, sunken eyes. Just because a man chooses to speak no evil doesn’t mean he doesn’t see it.

In a 1953 self-portrait, a similar juxtaposition carries a different expressive force. The face, the pose and the manner remain, only now the eyes are wide with fear and the fist by the chin seems protective, especially since the other hand clutches a bouquet of brushes. Armed only with art and sensitivity, Shahn stands between two sinister politicians who crowd him from either side. Like the American liberal tradition, he felt squeezed between Stalinism on the left and McCarthyite paranoia on the right. Individualism was under attack.

Shahn’s manner had evolved by then, and the draughtsmanship that had always undergirded his method now came into its own. He developed a distinctive line whose thickness and clarity varied along its length, depending on the expressive needs of each separate millimetre. Now heavy and blotched, now slender to the point of vanishing, that vital, electric line connected him with a mass audience. It was the perfect instrument with which to communicate with his bifurcated public: the “6mn people who understand Norman Rockwell” and the “60 who understand Picasso’s ‘Guernica’.”

The catalogue opens with Shahn invoking William Blake, who “said that righteous indignation over injustice was the truest worship of God. And I guess I am filled with righteous indignation most of the time . . . ” That constructive ire came out as a mixture of empathy and dissent — a style that was direct, eloquent, sincere, and muscular. We could use a few more Ben Shahns right about now.

To October 12, thejewishmuseum.org