Editor’s note: This is a follow-up story to the health care article published Oct. 29 concerning the 2023 Yampa Valley Behavioral Health Landscape Scan.

After 38 years working as a school psychologist, including more than 14 years with the Moffat County School District, Teresa Laster is more than ready to retire.

In fact, Laster, 65, officially retired in June, but she is back again working in the Craig schools for the 15th year because she did not want the mental and behavioral health and special education needs of the district’s 1,912 students to lack necessary support.

Laster gave three years notice to the school district for her anticipated retirement, and the position has been posted at least three times. Yet the district has attracted no viable candidates for the position that requires at least a master’s degree in psychology, said Cuyler Meade, MCSD director of communications and grants.

The National Association of School Psychologists notes a critical shortage in school psychology both for practitioners and the availability of graduate education programs and faculty needed to train workforce. The association recommends a ratio of one school psychologist per 500 students to provide comprehensive services, yet that ratio is estimated at one counselor to 1,127 and sometimes up to 5,000 students nationwide.

Attracting and hiring school psychologists and social workers is even more difficult in rural Colorado, Laster said, as the positions can pay thousands of dollars less than they do on the Front Range. Resort region housing costs and the start-stop nature of grant-funded social work positions also deters applicants.

Such gaps, opportunities and strengths in mental and behavioral health care support are the focus of the recently completed 2023 Yampa Valley Behavioral Health Landscape Scan. The study was commissioned by the Craig-ScheckmanFamily Foundation in Steamboat Springs and UCHealth Yampa Valley Medical Center Foundation and coordinated by nonprofit The Health Partnership of Northwest Colorado.

The “landscape scan” focused on specific populations in the valley including youth and young adults, the LGBTQ+ community in Moffat County and adult males working in the valley’s traditional economies, as well as Latinx-identifying members of those three groups. The study provided a deeper dive into the lived experiences and mental health needs in those categories.

“To date we’ve really relied heavily on surveys, quantitative studies, data from the state and anecdotal information, but we’ve never really stopped to listen to the experiences of the community in their own words,” said Bonnie Hernandez, director of impact at Craig-Scheckman.

Organizers say the deeper dive highlighted two common themes across groups: a general lack of open and normalized perception around mental health including stigma and how income inequality creates profound life stressors leading to mental health concerns and limiting the ability to seek formal help.

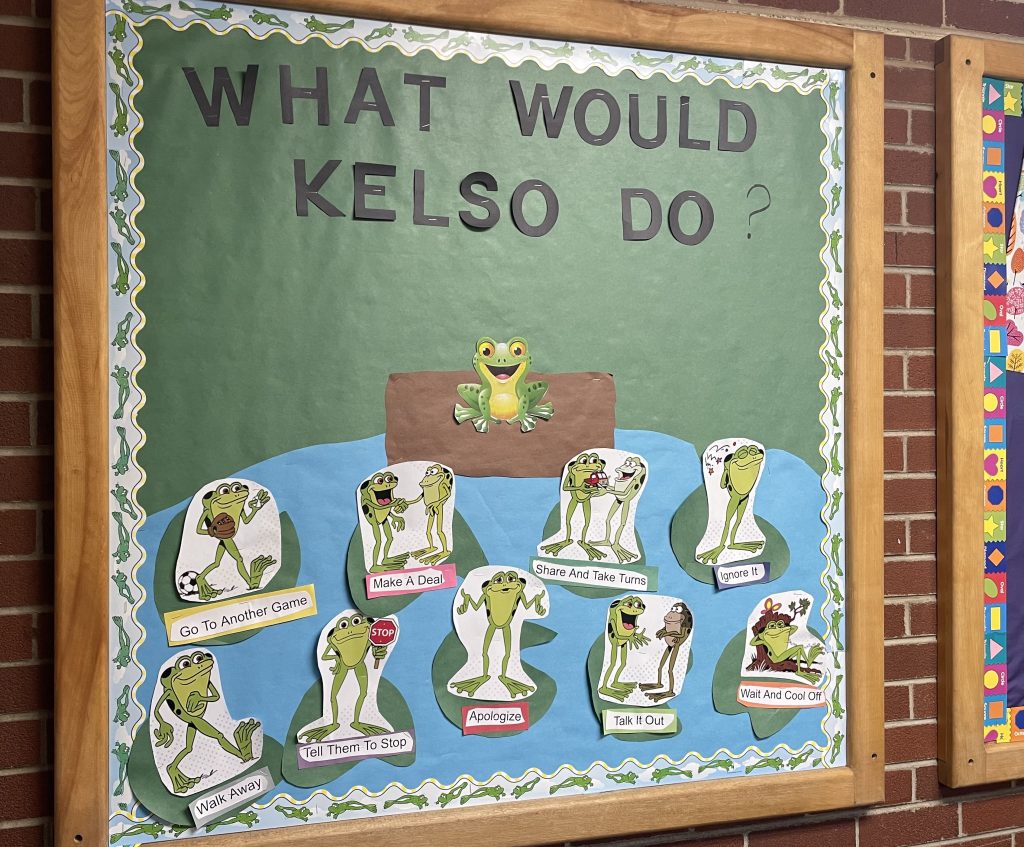

“A number of individuals and organizations work tirelessly to support young people in the Yampa Valley, but their ability to reach all young people is limited by resources,” according to the 77-page landscape scan. “Bright spots include efforts by Northwest Colorado Health that provide school-based mental health promotion including youth resiliency training and Partners for Youth, who provide school-based mentors in select schools in Routt and Moffat counties.”

Stephanie Einfeld, CEO of Northwest Colorado Health, said the nonprofit will use results from the landscape scan to inform the agency’s 2024 strategic plan, noting the agency’s Youth Resiliency Program “is a promising practice for youth in the valley.”

Similar to other rural school districts, Moffat depends on a combination of contracted services provided online as well as partnerships with area nonprofit and health care agencies to meet the needs of students. This year, the district contracted with Summit Psychological Assessment and Consultation in Colorado Springs, with an employee working virtually from Boulder, Laster said. The district also uses virtual services for special education student needs such as speech and occupational therapy.

“Virtual services are not ideal; it’s a fallback,” Meade said. “It’s not what we want to be doing long term.”

Meade said the concern when relying on students getting care outside the schools is that some kids might fall through the cracks.

“We are going to miss kids we could serve in the school building who we frankly need to serve in the school building because they may never get care,” Meade said. “We know from observations of our own students, there is a huge need for mental and behavioral health support.”

The school psychologist said the district “depends heavily” on the communitywide Individualized Service and Support Team, which is a team of school, nonprofit agency and human services staff who meet with eligible youth and their families who can benefit from integrated multi-agency services.

Laster’s job duties are extensive — family advocate, collaboration with community partners, initial testing for special education students, training for academic-focused school counselors and management of suicide, crisis and violent risk concerns. Plus, she works a second job as a social-emotional therapist for Horizons Specialized Services.

“I keep doing it because I love the kids,” Laster said.

If her wish were granted, Laster would retire and two school psychologists would be hired to help students in Moffat County schools.