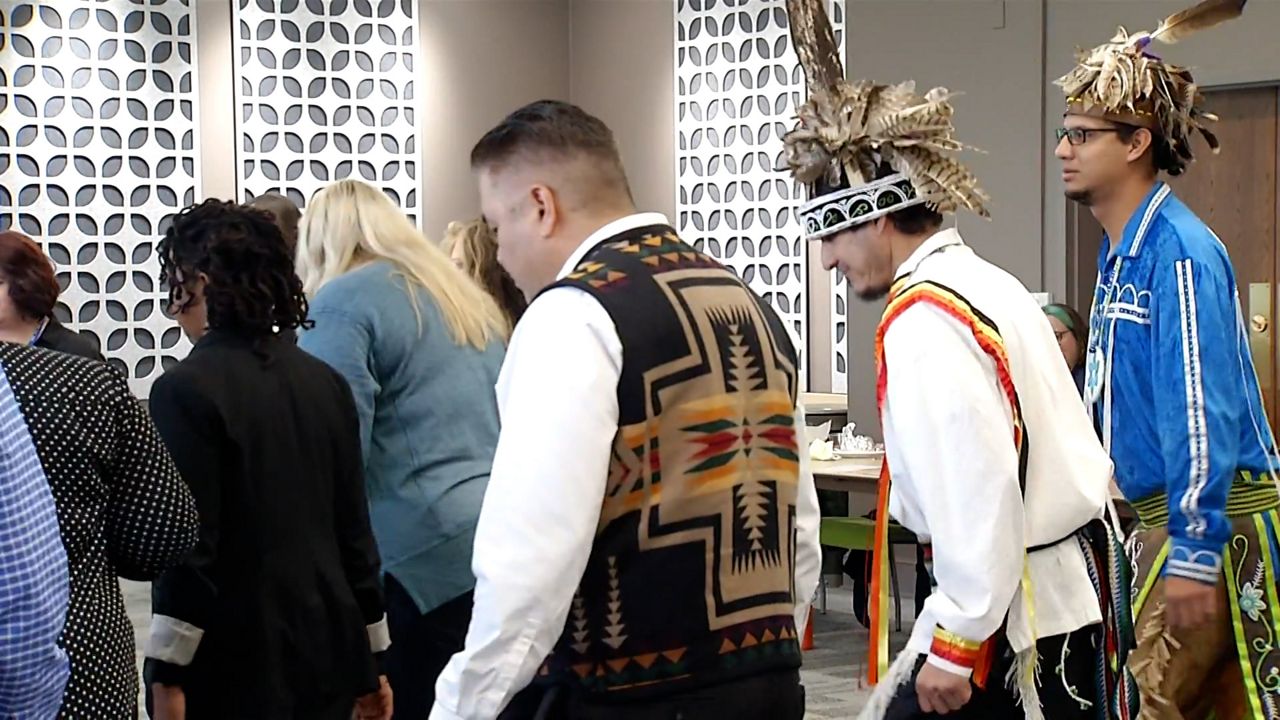

Three years ago, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo launched a program to further health equity and health care access through connecting Indigenous communities and cancer researchers. Now that program has expanded into a Department of Indigenous Cancer Health.

What You Need To Know

- The department is the first of its kind at a National Cancer Institute-designated cancer center

- Patient navigators say Indigenous people have higher rates in certain types of cancers, such as stomach, lung or breast cancer

- They say there are barriers to cancer treatment for the indigenous population such as transportation or hesitancy to seek out health care

This is the first department of its kind at a National Cancer Institute-designated cancer center. The new department focuses on research, education and clinical care relating to Indigenous populations. One important aspect of the department is integrated services, where patient navigators like Marissa Haring come in.

Haring is a community care navigator for the Department of Indigenous Cancer Health at Roswell Park. She works mostly on the Seneca Nation and Cattaraugus and Allegany Territories and for those who live off of the territories as well.

“I help do education, I connect people to resources, and I can help them get connected to screening too if they’re needed,” Haring said. “Or if they need extra support during or after their cancer treatments, I also do that as well.”

Haring is a member of the Seneca Nation. She’s Wolf Clan and lives in the Cattaraugus Territory. A lot of the patients she works with she already knows just from being part of the community.

“So I think it’s like a little more personal when I meet with them and it’s like, ‘Oh, we already know each other.’ And you have that like level of care for them just starting out with,” Haring said. “So I think it’s a lot more like personal connection and they trust us to help them through their journey as well.”

Haring says Indigenous people have higher rates of certain types of cancers, such as stomach, lung or breast cancer. She says many people aren’t aware of that fact, which is why it’s important to get the word out and get those of the Native American population screened. But there are also barriers to receiving healthcare for those who live on native territories like transportation.

“Other barriers might be like a hesitancy to seek out medical care due to historical trauma. A lot of people don’t trust the medical system, so they might need extra support there to tell them, you know, everything’s going to be okay. You can trust us. We’re going to make sure nothing happens. If there’s any issues, we can, you know, take care of those with you,” Haring said.

Teresa Van Aernam is a member of the Department of Indigenous Cancer Health’s community advisory board. She’s also wolf clan. Back in 2017, she had a mass on her ovary and had to get it surgically removed. What really stuck with her from that time was the support she received from patients with cancer and staff alike when she learned it wasn’t cancerous.

She calls the department a wonderful resource.

“I think in the future, as more opportunities become available, it will definitely highlight Native American health,” Van Aernam said. “We are in the era now where we have so much technology, technological advances and specific medicines that might be able to help Native Americans. We just really, I think, are at the very threshold of being able to have much more control over our health. I’d like to see our health for our indigenous people greatly improve.”

Van Aernam believes the Indigenous population is at the threshold of having more control over their health and she says she’d like to see health for Indigenous people greatly improve.

For more information on the Department of Indigenous Cancer Health’s services, head to RoswellPark.org.