LONDON — Es Devlin, the critically acclaimed set designer, does not eat meat or wear leather and admits to “not making much effort with her clothes.” Despite that, visuals are the language she understands best, underscored by three Emmy Awards; three Olivier Awards and a Tony Award for production design.

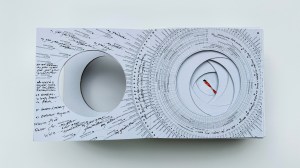

Her work ranges across mediums: theater, fashion shows, concerts, Super Bowl Halftime shows, installations and museum exhibitions that have now been encapsulated into an 858-page book titled “An Atlas of Es Devlin,” illustrating her prolific career through pull-outs, cutouts, different textured papers, mirrors and full-bleed images that run across double-page spreads.

A quarter of the way through the book, a gray booklet includes her conversations with other fellow creatives such as Virgil Abloh, Sam Mendes, Bono, Bjarke Ingels, Pharrell Williams and Yana Peel.

“An Atlas of Es Devlin” by Es Devlin.

Devlin compares the intricate tome she’s created to the Louis Vuitton bags that are handcrafted by hand she’s witnessed in the northern suburb of Asnières-sur-Seine.

“I hope this will be a bit like the way that you have to put your name down for a Birkin bag,” Devlin says in a British accent that’s both cheery and articulate.

“When I first started working in fashion. I didn’t understand anything about fashion at all. I literally turned up to a meeting with Nicolas Ghesquière wearing $1 black karate shoes with a brown plastic base,” she adds.

“An Atlas of Es Devlin” by Es Devlin

She’s been a longtime Louis Vuitton collaborator, overseeing Ghesquière’s productions, from his resort 2017 show in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil creating a red twisting runway, to his last show before the pandemic broke out, featuring a tableau vivant with 200 characters dressed in historical costumes that’s documented in the book.

Her first 5,000 prints of the books have already sold out in the U.S. and are priced at 85 pounds, a price point that she was very conscious of and wanted to reduce as much as possible — the book was originally priced at 200 pounds.

“A book, even for a young audience, can be an aspirational object, they might not be able to afford 85 pounds today, but it’s something they want to save up for, like a pair of sneakers might be. I’m really happy that that aspirational status can be applied to a book now,” Devlin says.

“An Atlas of Es Devlin” by Es Devlin

Her approach to her practice is a spiritual one that’s led by thought and attitude, she says.

“I never go into any project knowing what the outcome will be at all, I go in with a kind of faith that comes more and more with experience and age — that’s the beautiful thing about being 50 years old. I’ve really settled into trusting my process, trusting my collaborators and trusting that if I go in with the right sensibility, positivity and openness, then the ideas of the exchange will flow,” says Devlin, adding that her book was never going to be 2D, but rather a “bodily object” that one must engage with.

The book process proved overwhelming, and Devlin missed the deadline with publisher THames & Hudson by four years, she said. In that time, she was organizing the more than 260 projects she’s worked on.

Saint Laurent Men’s Spring 2023

“You didn’t get the sense of an artist with a clear arc, you just got the sense of a person who’d been very busy,” Devlin says.

The book now reads as a timeline of her life with major events such as 9/11, Princess Diana’s death and Brexit weaved in gently.

She’s noticed history, her own personal history and more broad history come together in hindsight, citing her 2005 theater production “Hecuba” as an example.

Louis Vuitton’s fall 2020 show.

“Of course we’d be doing Hecuba after the Gulf War; everyone was doing that piece that was written by the Greeks about the consequences of war, there were like five productions of it [at the time],” Devlin says.

The scale of her stage productions grew like towering blocks year after year. She’s collaborated on tours for Adele, Kanye West, and Beyoncé’s last two tours, “The Formation World Tour” and “Renaissance World Tour,” as well as the 2022 Super Bowl Halftime show featuring Dr. Dre, Kendrick Lamar and Eminem.

When it comes to telling Black stories with grace and sensitivity, Devlin often refers back to her own heritage that includes Indian, Armenian, Polish, Jewish and Islamic ancestry.

“An Atlas of Es Devlin” by Es Devlin

Her great-great-great-grandfather, a Scottish merchant in the East India Company married Eliza Kewark, a Gujarati woman with Armenian ancestry he met on his travels and had three children with her.

“He eventually got a job in Bombay and as the East India Company grew in stature in the colonial era, it was no longer considered acceptable to have a dark skinned wife or children. The children got taken away from her and brought to Aberdeen, Scotland,” Devlin says.

“She apparently couldn’t write, but would get a scribe to write letters every week and send them as she waited for her children and husband, who never came back,” she added. In Scotland, one of the children was ridiculed for the color of their skin.

“An Atlas of Es Devlin” by Es Devlin

“A lot of the music [of the artists she works with] is intuit of pain. Art is like an enzyme that can transform pain into works that can then go out into the world and transform other people’s pain,” Devlin says.

“The reason the artists are where they are is because they’ve already accessed that enzyme and are already translating it into art that then elicits more empathy. That’s really what we’re dealing with, it’s the eliciting of empathy,” she adds.