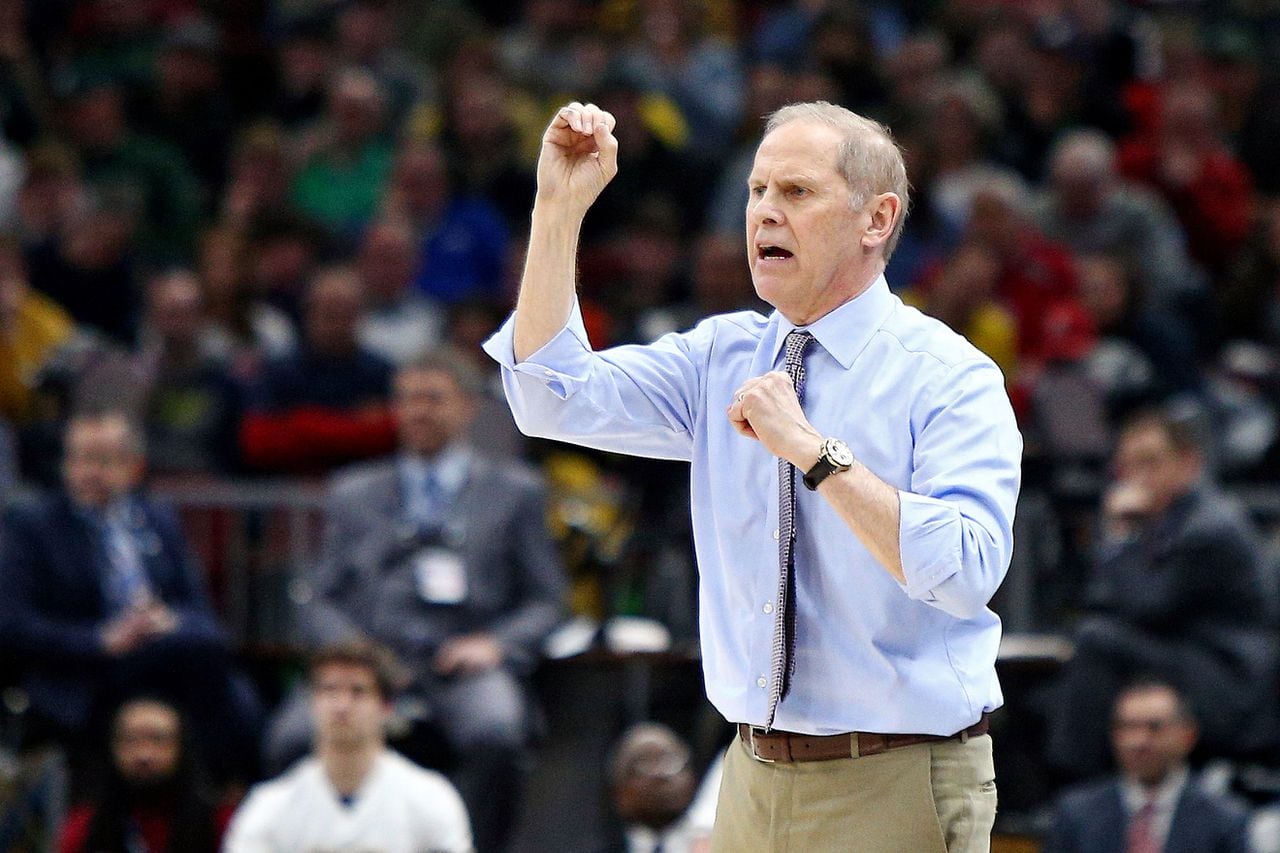

John Beilein was protective of his playbook during his college basketball coaching career. He once hesitated to tell a reporter, who just wanted an example to use in a story, the name of a play (any play). So, during his time at Michigan, when he noticed an opposing team’s assistant coach eyeing him during a game, Beilein took extra security measures.

The act of sign stealing — decoding a team’s play-call signals — has been a hot topic since the NCAA’s investigation into the Michigan football program’s alleged operation became public last month. Sign stealing, though, is not limited to football.

In college hoops, every coaching staff has a sign-stealing guy.

Here’s how it works, according to a dozen coaches who spoke with MLive this week: During games, most teams designate a staffer — sometimes an assistant, or maybe a director of operations — to watch the opponent’s bench. When a play is called — “tiger” or “five high” or a physical signal like a raised fist — the staffer makes a handwritten note, then checks the game clock and notes that too.

By the end of the game, he’s got a sheet full of time-stamped play calls. Later, using the game’s video feed, he can match up the calls with whatever action took place on the court.

Coaches vary on the value of this information.

In football, even a no-huddle, up-tempo offense needs a certain amount of time between plays. And those plays are less flexible than in basketball, which is more of a flow sport. Still, there are advantages to knowing what a basketball team is trying to do.

“It’s not about how a play ends, it’s about how it starts,” said one mid-major assistant who preferred not to be named. “If they’re trying to start with a ball screen or a down screen, if we can deny a pass to Johnny that messes the whole play up, that’s huge.”

Other coaches are less concerned. Say a defense knows a play will end in a corner 3 by the small forward. Cheating to deny that shot would likely open up something else.

“We tell our players to run a set but don’t be a robot,” said Wright State head coach Scott Nagy. “If other things open up, just be a player. In practice, I like it when the defense knows what we’re running. Can we execute it anyway?”

Sign stealing serves a purpose, or other coaches wouldn’t waste their time doing it. There was a time, veteran coaches remember, when coaches had to exchange film before an upcoming matchup. A coach from each team would have to meet somewhere in the middle or drive to the airport to put film on a plane.

Beilein, a college coach across five decades, recalled the issues that sometimes arose: the film angle was wide enough; the sound was cut off; the tape arrived after tipoff.

These days, with nearly every game televised somewhere, coaches can subscribe to analytics services like Synergy or Hudl and access high-quality footage of most any game they want.

If a team uses hand signals — a raised fist or a head tap — those can be seen on the video. Same, for the most part, with verbal cues.

Nothing beats in-person scouting, though, and that can only be done when two teams play each other. Aside from a tournament setting, off-campus, in-person scouting has been banned since 1994.

The current approach of in-game note-taking works for conference opponents that play each other multiple times per season. There’s no rules against that information being shared, and it often is.

Take Gonzaga, which plays Yale on Friday and faces Purdue 10 days later. Yale head coach James Jones would not be surprised if a member of the Purdue staff called one of his assistants this weekend and says, “Hey, you got any calls for us?”

To be clear, Jones was using those teams as an example. There would likely have to be preexisting relationship between the Purdue and Yale coaching staffs for that to take place. But the coaching community is close-knit; there usually is a connection.

“Sometimes it’s somebody we don’t want to help,” Nagy said with a laugh.

It was reported this week that football coaches at Ohio State and Rutgers provided another Big Ten team, Purdue, with Michigan’s calls in advance of the Purdue-Michigan Big Ten championship last season.

The basketball coaches who spoke to MLive for this story were unanimous in saying that kind of information-sharing does not take place.

“In league games, I just don’t know if that happens,” Nagy said. “Us trying to help each other? That feels odd to me that I would help one league team against another.”

There’s a similar line most coaches won’t cross either. Consider this example: Wright State and Oakland are both in the Horizon League. Oakland opened the season against Ohio State.

“We’re not helping Ohio State by giving them our calls about Oakland,” Nagy said. “We’re loyal to our league. I don’t know if everybody is that way. I just think that’s the right thing to do.”

Perhaps the biggest issue with Michigan football’s alleged scheme is the in-person scouting. The basketball coaches said they hadn’t heard of that happening in their sport, at least not to the extent of Michigan’s alleged operation.

Many fans have wondered why teams just don’t switch play calls regularly. Most don’t. “Every coach has his staples,” one assistant said. “But you’re always adding to your sets, tweaking things.”

Coaches will try to trick opponents in other ways. Beilein would sometimes tell his team one play in a huddle, then shout — for all to hear — the name of a different play. His players were instructed to run the original play. Jones’ Yale team has a play called “double high.” Later in the game, Yale might run “double high again,” which is actually a different play as opposed to “double high” again.

Wright State is set to open the season on Friday against Colorado State, which has an assistant coach who used to be on Nagy’s staff. “He knows all our calls,” Nagy said. “If I call an underneath out-of-bounds call and he tries to tell his players what we’re going to do, I think it can hurt them. They try to think instead of reacting.

“Big deal if you know our calls. You’ve still got to guard ‘em.”

Jones agrees. He wants his players to “read and react” to what the opponent is doing. “I could care less what the calls are for other teams,” he said. “But I know some coaches really get into that.”

Count Beilein among that group, or at least in the faction of coaches wary of sign stealing.

To combat it while at Michigan, he started calling very few set plays in the first half, when Michigan’s offense was shooting at the basket opposite its bench. If Beilein’s players had to look back at him for a call, so too could an opposing coach. And he found some doing just that, watching his every move like a “Dancing with the Stars” judge.

He’d only call plays during timeouts until the second half, when he could shield his body from the opposing bench while delivering the signal.

“It’s a big deal,” Beilein said. “They’re watching you.”