T

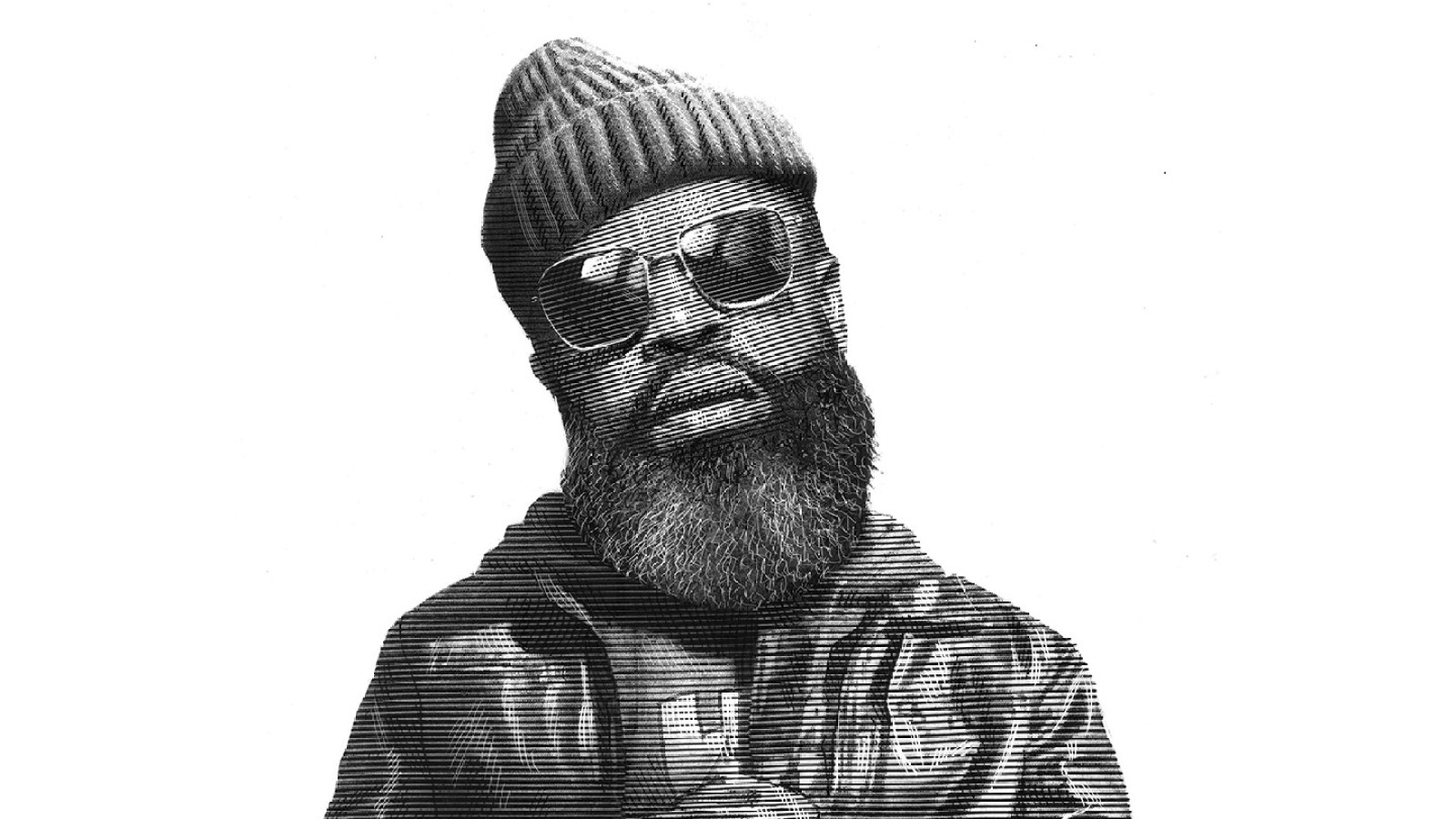

ariq Trotter, a.k.a. Black Thought, has given the world endless insight into his mind in the 35-plus years since he founded the Roots with his high school classmate Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson. But even after all those richly detailed lyrical flights and legendary live shows, he began to suspect he was holding something back. “It still felt as though there was a disconnect, and that fans of my work didn’t know me, the person, as well as they should or could after all this time,” he says. “So I began to think about ways to continue to tell my story.”

One result of that process is Trotter’s new book, The Upcycled Self: A Memoir on the Art of Becoming Who We Are (out Nov. 14). An essential read for anyone who’s nodded along to one of his prodigious verses, The Upcycled Self shines a revealing light on experiences he’s only hinted at before. We read about Trotter’s complex relationship with his late mother, who grappled with addiction, and about his own fierce love for the environment that created him even as he worked hard to escape it. We see how different he and Thompson were when they met at the Philadelphia High School for Creative and Performing Arts in the 1980s, and how their bond evolved over the years. In a poetic, profound voice that should surprise no one who’s followed his work, Trotter lets us in on the painful losses that have informed his music, and how he’s learned to reconsider those traumas as an adult. “The work of understanding our own humanity,” he writes, “begins with returning complexity to the people who shaped us, in lieu of granting sainthood.”

The new memoir is a highlight of a creative time for Trotter that has included multiple solo albums (including this past spring’s excellent Glorious Game, recorded with El Michels Affair) and a provocative off-Broadway musical, Black No More, in addition to dozens of awe-inspiring concerts with the Roots and nightly appearances on The Tonight Show.

Trotter spoke with Rolling Stone about artistic growth, the view from age 50, the unreleased music in the Roots’ vault, and much more.

You write that you were “an introverted kid.” Would you still describe yourself that way now?

Yes, definitely. Sometimes to a fault. It’s a gift and a curse. Through that introversion and in that pause, I’m able to answer the call: That’s where the ideation takes place, and that’s where the imagination kicks in. If I always had that outside stimulus of interacting with actual people, I don’t know that I would be as deep a thinker or as in tune with myself as I am. But the opposite side of the coin is the social expense and the awkwardness.

This is what I tell my kids, my students, my mentees: “Don’t be so desperate for friendship that you’re accepting all offers. Be selective and be wise in the friendships that you forge.”

People might assume that someone who’s as comfortable on the mic as you would love talking to people. But that’s not always the case, right?

One would think that. I’m not comfortable being in front of people or sharing myself with the world, but I understand the necessity of it. It’s a means to an end. I’m only going to be able to go so far without opening up. I don’t particularly enjoy it, but it has to happen if I want my music and my art to continue.

You just turned 50. How did you celebrate?

I went away for almost a week, my wife and I. I can’t remember the last time we got away for that extended period of time. We went to Mexico, got to be active a little bit and hike and zip line, and just chill. It was a great way to end a summer of heavy touring, and also the 140-some-odd days of uncertainty of the writers’ and actors’ strikes. A nice little bookend. And then I came back.

What’s the best advice you’ve ever gotten?

The best advice I’ve ever gotten in my life is, “Everyone is not your friend.” That’s one of my Grandma Minnie’s jewels. I never agreed with that. I thought she was crazy. But she was always right. This is what I tell my kids, my students, my mentees: “Don’t be so desperate for friendship that you’re accepting all offers. Be selective and be wise in the friendships that you forge.”

Fans spent years wishing you’d make a solo album, and lately you’ve given us some really strong ones. How has it felt to access that side of yourself, making music outside of the Roots?

It’s fulfilling. I’m not doing anything differently now than I have for years and years and years, other than I’m giving my audience entree now into the war room. I’m turning the drawing board around and saying, “This is how I arrived at what I arrived at in a Roots capacity.” I’ve always recorded lots of music in the Roots and outside the Roots, but for a long time it never got to see the light of day. So what I started in 2018, when I started putting out the Streams of Thought albums, was just showing you my sketchpad, my notebook: “This is what I do in between the Roots albums.” It spoke to a void, and it’s been able to serve that purpose of bridge-building between me and some of my fans.

On the one you released this year, Glorious Game, you sound like a more mature artist. You’re not the same guy who made “Clones” or “Proceed” in your twenties.

Absolutely. Different, more mature, more experienced, wiser. Probably a little jaded and more of a realist. Bruised, battered, scarred.

When you do perform those older Roots songs now, how does it feel to revisit that part of your life?

Songs that we’ve been performing for the mainstay of our career have been the more general joints. There’s always some songs that are really personal — but for all intents and purposes, those aren’t the songs that have stood the test of time. They’re the deeper cuts. People may think that “You Got Me” or “Silent Treatment” or “The Hypnotic” came from real experiences. But those were essentially audio screenplays, and I just was able to weave those stories in a way that made it relatable.… I don’t really have that personal connection that people might think I do in performing those songs. For me, it’s just a song I wrote when I was 18, 19, 20 years old. It’s not like it’s gut-wrenching for me.

What’s an example of a deeper cut where you did reveal a little more of your real self?

One of the realest songs I’ve ever written — a big, emotional, heavy record for me that was challenging to make — was “Clock With No Hands.” I’ve performed it maybe three times…. If I’m talking about “Clock With No Hands,” that came from so many actual places and real relationships in my life, that’s the sort of thing that could move me to tears.

Next year will mark 10 years since the last album you released with the Roots. Why has it been so long?

It feels a little unnecessary. There may be some aversion associated with putting out music in the absence of Richard Nichols, who was our longtime manager. Rich wasn’t a musician, but he was very much a member of the Roots. [Note: Nichols died of leukemia in 2014.] There’s lots of music. We could put out an album tomorrow if we needed to. The reason we haven’t has to be some anxiety. There’s a blockage associated with putting out music without that fifth member of the Beatles, so to speak.

Now, do I feel like, because Rich is no longer with us, that we can’t go on? No, I don’t feel like that’s the case. But a lot of this stuff is unforeseeable. You can’t even speak to it until you’re there at that point in time.

What kind of unreleased Roots music is there in the vault? Are there things that people would be surprised to hear?

We’ve got experimental stuff, music that we’ve recorded sometimes riding a wave or trying to get ahead of a wave. Sometimes you just forge organic friendships with an odd cast of characters. Artists that you become friends with that, from the outside looking in, might be more of a head-scratcher. People wouldn’t expect for there to be music with Black Thought and Project Pat, you know what I’m saying? But it exists. There’s lots of stuff like that. You go through the whole rigmarole of feeling out a thing to see if this is going to work. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. And you amass over time this vault.

It’s a different urgency to create and to continue to evolve. It becomes that much more important when you realize how many people that began the journey with you aren’t going to be there with you physically in the end.

You write beautifully in the book about your friendship with Ahmir, and how it’s changed over time. How would you describe your relationship with him now?

We are brothers who interact in the way that anyone who has a sibling that they’re close in age with would interact. There’s also a dynamic of marriage. We’re brothers who are married, and that’s how we interact. Speaking to that whole unspoken-ness of it, there’s much that we’re able to communicate in a word or a look or a tone. And I appreciate that. It’s above and beyond that true friendship that my grandmother spoke of.

You’ve also lost two former bandmates from the Roots since 2020 — Malik B and Leonard Hubbard. How have those losses affected you?

It makes one more conscious of where you are in life. What am I able to do with the time that I have left? How much have I taken for granted? It’s a different urgency to create and to continue to evolve. It becomes that much more important when you realize how many people that began the journey with you aren’t going to be there with you physically in the end.

In terms of the bigger picture, we’ve seen so many great MCs from your generation die in the last few years, from DMX to MF DOOM. Is there a risk of something being lost there, a cultural memory slipping away?

I think the risk of loss comes in when we cease to tell the stories of these artists. Once the DMXs and Malik Bs and MF DOOMs of the world and their contributions become disposable, then yeah, that’s where we’ve lost. But as long as we continue to tell their stories and continue to run with and add on to styles and cadences, that’s what keeps their legacy alive. I mean, you think about Malik, DMX, and DOOM — these are three distinctly different calibers of MC, but all three MCs no less. All three forces to be reckoned with who changed the approach for so many artists who were part of our generation, and then for generations to come.

Hip-hop turned 50 this year, just like you. Do you still connect to the music that’s being made by the younger generations?

Not all of it. I don’t think that it’s being made for me, so to speak, but I’m able to appreciate it. Hip-hop has already taken over the world, and I think the universe is the limit. We’ve all been able to feed ourselves and build these beautiful lives and send our kids to school, while continuing to add on to this thing that we love. You talk about the invention of the wheel and shit like sliced bread and fire — stuff that revolutionized humanity — I think hip-hop is one of those things. I’m just super grateful.