He lost half of his hearing in Saigon. He will never forget the deafening machine gun fire or the roar of 122-millimeter rockets that came within a few hundred meters of incinerating him in 1968.

His nightmares are as vivid as ever. Every few weeks for decades, it has been the same bad dream: slow torture at the hands of the Viet Cong.

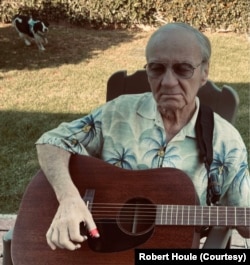

“Dr. Robert Houle” is what he scrawls on government forms. He prefers, though, to be called Bob the Entertainer. That’s the name he has made for himself touring the retirement homes of Southern California, strumming his Martin guitar and crooning hits from bygone years, from “Oh, Pretty Woman” to “If I Had a Hammer.”

In any given month, Bob, now 77, performs at least a dozen such gigs. He’s in high demand among old age home event-planners. His audiences range from retired A-list celebrities and athletes to fellow veterans, like one former airman who flew bombers over Germany.

“When you’re singing, you feel relief,” Bob told VOA. “You’re spreading love.”

‘Rediscover your voice’

Five decades may have passed, but this Veterans Day, the horrors of the Vietnam War still haunt tens of thousands of survivors grappling with post-traumatic stress disorder, also known as PTSD.

Some, like Bob, have turned to performing to find peace.

“PTSD really shuts people down and keeps them from doing the things they used to enjoy, the things that make life meaningful for them,” said Dr. Sonya Norman of the National Center for PTSD. “So, to rediscover your voice and create music can help you reclaim your spot in the world and feel valued.”

A lifetime ago, in 1961, Bob dreamed of a career in music after hearing Peter, Paul and Mary’s debut record. He saved up his earnings as a newsboy until he could afford a flimsy fiberboard Silvertone, the cheapest guitar money could buy.

He spent days on end sequestered in his bedroom, learning songs on the radio by ear. Within a year, he had mastered the instrument, harnessed his soft tenor, and formed a duo with a friend named Tony. On weekends, they would perform at local juke joints and pizza parlors for free grub.

Growing up in the palm tree-lined suburb of Fullerton, California, music was his escape from a disturbed home life.

Bob said his mother couldn’t have cared less about him. His father was a violent man, a “knuckle-dragger kind of guy.” To the best of his recollection, neither ever hugged him, kissed him, or told him, “I love you” or “I’m proud of you.”

Bob was in junior college when he received his draft notice in 1966. A few days later, he enlisted, ready to get away from his parents. Despite barely graduating from high school, he aced the Army entrance exam, meaning he could choose from any assignment.

Bob told the recruiter he wanted to be a spy. “I thought I’d be James Bond or something,” he said, chuckling.

Becoming a spy

In some ways, the trauma of his abusive family prepared him for basic training at Fort Lewis. For two and a half months, drill sergeants foamed at the mouth, screaming, “You’re going to die! You’re lower than whale dung — and whale dung’s at the bottom of the ocean!” Their other catchphrases are unfit to repeat.

A top-secret Army Intelligence training program was next — “spy school” as Bob calls it. There, he became versed in all manner of spycraft.

Brush passes and dead drops. How to enter a country surreptitiously. Writing in ciphers. Drafting secret communications using lemon juice for invisible ink. Microdots, or pictures as fine as heads of needles, could be hidden beneath postage stamps and fingernails and resized under strong magnification.

This was a secret agent’s repertoire. Detection, Bob said, almost certainly meant dying in barbaric fashion, but not before torture so harrowing and humiliating that most men would lose all hope of return. Article 46 of the Geneva Conventions specifies that a caught spy has no right to treatment as a prisoner of war, leaving open all kinds of horrific possibilities.

Dodging close calls

At the height of the Tet Offensive, four secret agents — men who had trained with Bob at spy school — were captured at Hue and booked for an extended stay at the Hanoi Hilton, a place of murder, rancid dinners, dislocated limbs, windowless confinement, and strange methods of extraction.

Former U.S. Senator John McCain and other survivors spoke of how they were bound with ropes, their bodies contorted at impossible and excruciating angles. They said the Viet Cong starved prisoners and stuck them with butcher’s hooks. They locked them in leg stocks for days and weeks at a time.

“Talk about scary,” Bob said shakily. “Those guys did what I did. Luckily, I was never caught. But, you know, there were close encounters, and you always had to be prepared.”

PTSD catches up

After the war, Bob earned three diplomas, including a doctorate under Carl Rogers, the father of humanistic psychology. Over the past half-century, Bob has worked variously as an insurance salesman, hypnotist, DJ, consultant, motivational speaker, and, of course, guitarist-for-hire.

But for most of those years, Bob denied anything was wrong. Twice divorced and three times married, he found the unresolved grief of war took a toll on his personal relationships.

Following a string of nervous breakdowns in the mid-2000s, he finally consulted a psychiatrist, who diagnosed him with PTSD within minutes.

“He told me that I had a classic case of it,” Bob said. “You can’t go into a war zone and not get it.”

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, an estimated 9 million Americans suffer from PTSD, which is especially common among veterans.

Finding acceptance, embracing optimism

Now, Bob lives peacefully in sunny Costa Mesa, California, with his wife April (who “doesn’t take crap from anybody”), their three cocker spaniels, and pet canary.

Acceptance and optimism, he believes, are crucial to healing. He has made breakthroughs recently with his therapist during bi-monthly Zoom sessions. But he doesn’t think he could’ve made it this far without his guitar.

“Most of the good things that have happened in my life came through music,” he said. “Music got me through my childhood, and it got me through Vietnam, too. I had my guitar with me in Saigon.

“I sing because it’s what I love. I sing to heal, and I still have a lot of healing left to do.”

Rebecca Vaudreuil, a leading music therapist sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts to help veterans struggling with PTSD, said “music is a way to make peace, to bring back meaning.”

War can devastate a person’s outlook on life. But song, said Vaudreuil, is a universal language that unifies and uplifts.

Go to any of Bob’s shows for proof of that. After he strums his first chord, pensioners whose joints have long since given out suddenly dart up like spring flowers, chanting, clapping, and twirling as if 50 years younger.

“The reason I sing,” Bob said, “is to feel connected to the people around me, to feel heard.”

Survivors of the Vietnam War, America’s most fatal conflict since World War II, are dwindling in numbers. Those veterans came home uncelebrated to a divided nation. There were no ticker-tape parades then. Still today, their hardships go unheard.

Part of the therapeutic power of music, Vaudreuil and Bob agree, is in feeling listened to, particularly at a time when more than 6,000 veterans die by suicide each year in the U.S., according to government data.

Bob often describes his battle with PTSD using an analogy his mentor Carl Rogers once told him.

“Picture this,” Bob said. “There’s a man trapped beneath a sewer grate in busy Manhattan, crying out for help. The steam is rising up through the metal slats onto the street corner, and thousands of passersby above ignore him. But all it takes is one person to look down and say, ‘I hear you.’ That’s where the healing starts. That’s what music is to me.”