Fifty years ago last month, Erica Jong published a debut novel that went on to sell more than 20 million copies. “Fear of Flying,” a book so sexually frank that you may have found it hidden in your mother’s underwear drawer, broke new ground in the explicitness of writing by and for women. Jong’s heroine, Isadora Wing, was a live wire. She was also a dead end, certainly for Jong, and maybe for feminism, too.

Born in 1942 to a family of freethinkers in Manhattan, Erica Mann, who became Erica Jong, belonged to a generation “raised to be Doris Day,” as she later wrote. Her Barnard yearbook photos showcase the full early-1960s checklist: velvet headband, twin set, pearls. Jong was gifted and ambitious. But even as a literature major at one of the country’s most distinguished women’s colleges, she had read vanishingly little work by female authors. She wed shortly after graduation, and when that starter marriage fell apart, she entered a second, to a Chinese American psychoanalyst, Allan Jong.

Jong left Barnard in 1963, the year, as the poet Philip Larkin joked, that “sexual intercourse began.” The F.D.A. had approved the nearly foolproof oral contraceptive that came to be known as the pill. Literature was growing raunchier. Several years earlier, the Supreme Court had declared that “sex and obscenity are not synonymous,” clearing the way for American editions of “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” and “Tropic of Cancer.” Shortly after Jong’s graduation, Mary McCarthy published “The Group,” a novel whose frank depictions of birth control, female orgasm and sexual violence led several countries to ban it for obscenity. In the United States, “The Group” was No. 1 on The New York Times’s best-seller list for months.

During Jong’s final semester, Betty Friedan had published “The Feminine Mystique,” based on interviews with Smith College graduates schooled to rule the world only to find themselves marooned in the suburbs wondering, “Is this all?” It, too, became a best seller. But though feminism existed as a term and as a centuries-long body of political thought, it was not, as Jong well knew, a curriculum, much less a social movement.

Things changed fast. In 1966, Friedan and 48 others, Black and white and Latina, chartered the National Organization for Women. Pauli Murray, a co-founder and civil rights pioneer, described the organization as “an N.A.A.C.P. for women.” By 1968, NOW had hundreds of members in chapters around the country, fighting against sex discrimination in employment and for paid maternity leave. Other feminists wanted more thoroughgoing transformation, including the abolition of the nuclear family. That September, one of the revolutionary groups, New York Radical Women, picketed the Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City in the name of what was called, for the first time, a women’s liberation movement.

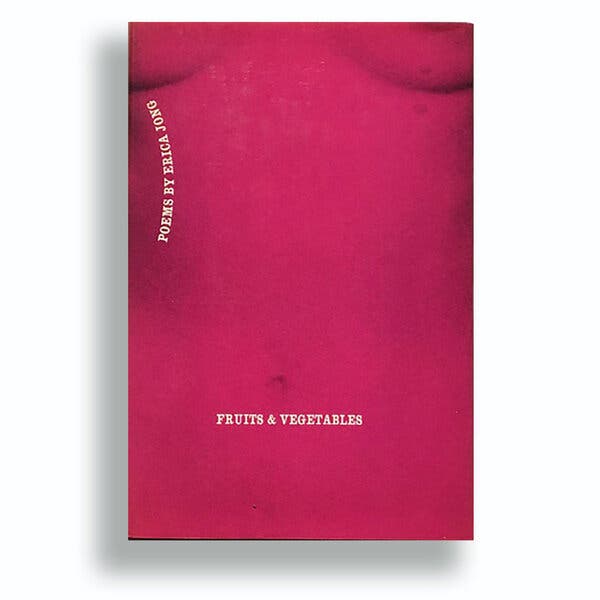

Jong embraced women’s lib, having felt the famous “click” of recognition when she read Sylvia Plath’s furious posthumous collection, “Ariel.” At Columbia, where she attended graduate school in literature, Jong set aside her research on the 18th century and piled up drafts of blank verse, convinced that publishing “a volume of poems would change my life.” Holt offered her a $1,200 advance for her first collection, “Fruits & Vegetables,” published in 1971. The book featured a provocatively cropped nude female torso on its fuchsia cover. At the launch party, held in a produce market, Jong dressed in her vision of the liberated, liberating auteur: “purple lace hot pants” and high-heeled sandals. The “properly improper” poet made the evening news and then the 92nd Street Y. In April 1972, she won an award to support a second collection. By then, she was hard at work answering a suggestion from her editor, Aaron Asher, who had told her that she ought to write a novel.

Asher was known as a turnaround artist; Holt had hired him to revive its sagging trade book division. He had edited a stable of literary eminences including Arthur Miller and Saul Bellow; he soon picked up Philip Roth: the big boys. At Holt, Asher also took a chance on a first novel by a Black feminist writer: Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” (1970), which testified less to a feminine mystique than to an American tragedy.

But neither Asher nor Holt had yet cashed in on the dawning vogue for novels of sexual liberation from a woman’s perspective. Random House had issued “Such Good Friends” (1970), by Lois Gould, a roman à clef about a woman who discovers a secret diary detailing her husband’s affairs. That year, Simon & Schuster published Anne Roiphe’s “Up the Sandbox!,” in which a mother of two small children drifts into sensual reverie as she goes about her chores. And in 1972, just as the Equal Rights Amendment roared out of Congress to the states, Knopf brought out the most movement-aligned feminist novel to date: “Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen,” by Alix Kates Shulman, who had helped to organize the Miss America demonstration. It quickly sold more than a million copies.

Gould, Roiphe and Shulman wrote auto-fictions: Freud’s Dora penning her own case history. Their narratives are skeptical of love, riddled with divorce, fluent in abortion. Shulman’s novel features a gruesome illegal termination, “a real baby” literally flushed with the toilet water. Yet in her book, as in the others, the world beyond the body scarcely exists.

Jong would outdo them all. In 1972, she signed a contract with Asher and Holt, accepting an advance of $15,000 for a novel to be called “Fear of Flying.” As galleys began to circulate, they were stolen and shared, like samizdat for a sex-positive feminist underground.

The Supreme Court handed down its decision in Roe, legalizing abortion, in January 1973, as Jong worked through page proofs. Then, that summer, the court delivered a set of opinions that made it easier to prosecute works deemed obscene. An era of cultural libertinism, symbolized by the runaway success of the hard-core film “Deep Throat,” seemed to be ending.

Jong knew she had written a daringly explicit book. The rulings “terrify me,” she told the poet Adrienne Rich, imagining “‘Our Bodies Ourselves’ confiscated.” Yet when a friend teased her about posing as “a sex object” for her author photo, Jong pushed back: “After centuries of patriarchal oppression, all’s fair in love and book publishing.”

Like many first novels, “Fear of Flying” is both ambitious and uneven. “I wanted to write about the whole world,” Isadora insists: to use a telescope as well as a speculum. She feels little affinity with history’s “uncertain heroines” and their “severe, suicidal, strange” tales. “Where was the female Chaucer?” Isadora goes on a pilgrimage to find her.

Isadora’s reach exceeds her grasp. Her desire to write the whole world notwithstanding, “Fear of Flying” is a sexual self-portrait, kin to the self-examinations women’s groups undertook on living room floors, or to “The Dinner Party,” the installation of sculpted vulvas on ceramic plates that the artist Judy Chicago was working on in 1973. It is also a road novel, a hedonist-feminist Kerouac. Isadora flees her husband, and his psychoanalytic conference in Vienna, to race through Europe with a manifestly deficient paramour, Adrian Goodlove, in pursuit of a “platonic ideal” she calls “the zipless fuck”: sex without past or future.

A proud feminist, Isadora has trouble squaring her movement principles with her “unappeasable hunger for male bodies.” Six Freudian analysts have treated her, yet she remains a mystery to herself. She has not given up on the marriage plot but can’t conquer the “other longings which … marriage did nothing much to appease”: “the restlessness, the hunger, … the longing to be filled up,” to be penetrated “through every hole.” Jong has ditched her twin set and pearls.

There is a lot of sex in “Fear of Flying,” but the novel is rarely sexy. Intercourse, relentlessly anatomized, fails to delight Isadora, much less the reader. “I longed to have orgasms like Lady Chatterley’s,” she sighs. “Why didn’t the moon turn pale and tidal waves sweep over the surface of the earth?” Goodlove looks “like Christ at the Last Supper,” but belies his last name in bed. Ziplessness proves a mirage. The threat of pregnancy looms; Isadora quips that she is “virtually the only one of my friends who’d never had an abortion.” Her journey ends not with marriage but with menses: blood everywhere and nary a tampon in sight. The medical director of Tampax accused Jong of misusing its trademark, in a warning letter that reads like a page from her picaresque gynecological satire.

A whiff of misogyny hangs over the book’s many reviews written by men, most pointedly in the British press. A young Martin Amis damned the book as mere autobiography and declared, “I neither know nor care whether all the horrible and embarrassing things in this book have actually happened to Miss Jong.” Paul Theroux compared the “witless” Isadora to “a mammoth pudenda, as roomy as Carlsbad Caverns” — such erudite revulsion for the organ Jong reclaimed in four letters.

Yet female critics proved little friendlier. The Nation sent women reviewers after Jong twice. The first accused her of writing in the “unwelcome” confessional style favored by women’s libbers; the second damned her for writing like a man.

In the end, a single male reviewer cemented the book’s success. In an essay for The New Yorker aptly titled “Jong Love,” John Updike proclaimed that Isadora Wing was Holden Caulfield minus the boring idealism, Alexander Portnoy without the cruelty. Jong, Updike said, could “now travel on toward Canterbury,” as the female Chaucer Isadora longed both to read and to be.

Signet emblazoned a phrase from Updike’s review on the book’s paperback cover in November 1974. The book reached the top spot on The Times’s best-seller list the following January; by May, some three million copies had sold. Soon Jong appeared on “60 Minutes.” Playboy ran a lengthy interview with her. At just 33, she was suddenly “a public personality.” By then, Jong had been paid a million dollars to write a sequel, “How to Save Your Own Life.”

She would need that advice herself.

An ancient and eminent male poet who had championed Jong’s verse warned: “Don’t overdo those tempting genitals.” Like a lot of the advice men offer women, it appears to have been unsolicited. It was also prescient.

Celebrity turned Jong inward, as an early poem had predicted: “I’m good at interiors … & have no luck at all with maps.” She bared all, in interview after interview. A profile in Newsweek ran with a snapshot of her in the bath at 13, soapsuds to her breast buds, Lolita come to life.

Fan mail drowned her. The letters were filthy, fond and heartbreaking. “If I answered them all I would never write another book,” Jong wrote in New York magazine.

She published many more books, all essentially the same, including three more Isadora novels and two volumes of memoir. The academy, which had scooped her up eagerly when “Fruits & Vegetables” and “Fear of Flying” broke barriers, dropped her just as fast when she eddied in underwear. Encouraged to peddle their “fleshy fables,” popular women writers were “dismissed by the lit crit crowd as trashmeisters,” Jong later wrote.

Bitter but true; her writing is not much taught or studied. A couple dozen dissertations center on her work, about a tenth as many as those analyzing Roth. “‘Fear of Flying’ had seemed an apprentice work to me when I wrote it,” Jong recalled, “and now it was to be my tombstone.” But she kept polishing that cenotaph; by the time “Fear of Fifty,” Jong’s “midlife memoir,” came out, her fax machine was programmed with the header “A ZIPLESS FAX FROM ERICA JONG.”

In 1980, Putnam published “The Decade of Women: A Ms. History of the Seventies in Words and Pictures.” “Fear of Flying” — which, as Jong plausibly claimed in a wounded letter to Gloria Steinem and her co-editors, was “probably the most widely read feminist book of the decade” — was not listed. In response the Ms. editors invoked the hard choices anthologists make, signing themselves, “in sisterhood.”

Sisterhood had never reckoned effectively with sex or pregnancy, Jong argued in “The Awful Truth About Women’s Lib” in 1986, after an anti-feminist backlash had set in. “The trouble with the second wave of the feminist movement in America was that it did not address itself to the 90 percent of women who had, or wanted to have, babies,” she wrote. True enough. But Jong had wielded her pen in a different battle: the struggle for women’s pleasure, fought during that fleeting moment when sex struck some feminists as the thing that would set us once and forever free.

The decades have proved them wrong.

Several publishers issued 30th-anniversary editions of “Fear of Flying”; Holt and Penguin Classics promoted a deluxe 40th-anniversary version; and Berkley has an edition pegged to the 50th anniversary coming in December. Today every woman is Isadora. Or maybe none is. Americans are lonely — marrying less, partnering less, even having less intercourse than ever. Women’s self-determination is found nowhere in the Constitution. Pay equity has barely budged in 50 years.

The marriage plot, the abortion plot, the screw-me-sideways-without-a-zipper plot: Each has run its course without effecting the longed-for revolution. Many of today’s feminist narratives wallow in pain more than pleasure. Isadora, as prescient as she was ineffective, seemed almost to sense it coming: “Growing up female in America. What a liability!”

Jane Kamensky’s next book, “Candida Royalle and the Sexual Revolution: A History From Below,” will be published in March.