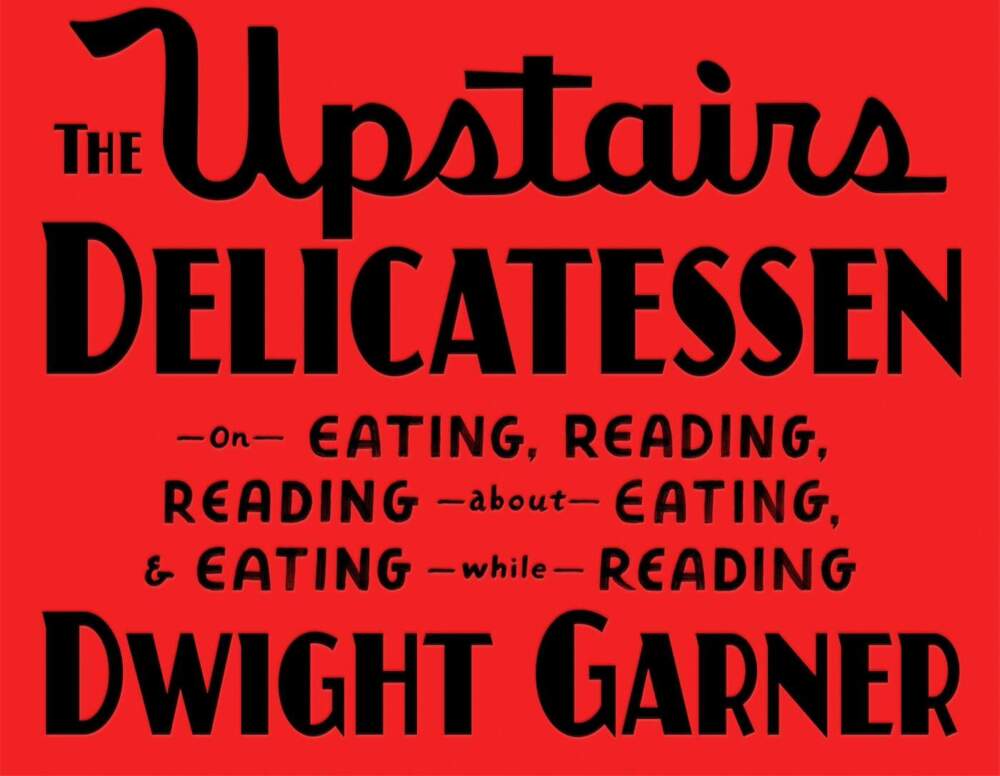

If ever a book was meant to be savored, it’s Dwight Garner’s new memoir

“The Upstairs Delicatessen: On Eating, Reading about Eating, and Eating While

Reading.”

In it, the New York Times literary critic takes readers on a journey through his food and book-obsessed childhood, infusing it along the way with the words of the great writers who have moved him from his childhood in West Virginia and Naples — where he ate his father’s legendary peanut butter and pickle sandwiches — to his marriage to chef who grew up bringing leftover frog legs to school in her lunch box.

Garner joins host Robin Young to talk about his new book and his lifelong passion for reading and eating.

Book excerpt: ‘The Upstairs Delicatessen’

By Dwight Garner

When I was young, growing up in West Virginia and then in southwest Florida, I was a soft kid, inclined toward embonpoint, “husky” in the department-store lingo, a brown-eyed boy with chafing thighs because I liked to eat while I read—and, reader, I read whatever was handy. George Orwell described his childhood self as having a “large, rather fat face, with big jowls, a bit like a hamster.” This was my look, too, so much so that my friends presented me with a hamster as a joke gift. I regret to inform you that I named it Holden, after J. D. Salinger’s hero. Holden ate lettuce and, probably despairing of his diet, staggered backward theatrically on his hind legs one day and croaked, like Lee Marvin in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

I was eight when we moved south. My parents were in flight from West Virginia’s long, isolating winters. They were done carrying pots of boiling water out to dump over ice-sealed car doors. I spent my first week in Naples miserable, uprooted, in exile, missing my friends, intermittently weeping, sometimes performatively, and listening nonstop to the first record I’d ever asked for: John Denver’s new one, Poems, Prayers & Promises, with “Take Me Home, Country Roads” on side two. Here was my plight, articulated exactly, a rare thing at any age. I already missed West Virginia’s mountains and the way the weather boiled up from them. I missed the way the light is dealt out through the peaks. I was even homesick for Charleston’s paper-mill reek and the stacks of rusted cars and refrigerators in the valleys that one politician called “jumbled jungles of junkery.” Naples, on the other hand, popped like a postcard. I didn’t trust it. There was something predatory (all those alligators eyeballing you from the ponds) and flimsy about every sun-splashed, underground sprinkler–mined, golf course–adjacent acre. Cynthia Ozick would write, “The whole peninsula of Florida was weighted down with regret. Everyone had left behind a real life.”

I attended Saint Ann, a middle school with a Catholic church attached. The girls wore plaid skirts and short-sleeved white dress shirts; boys wore dark trousers and strangely casual teal T-shirts. It took me a long time to find friends. When classes began, so did a daily ritual that became the most important thing in my life. I’d bicycle home under the Gulf Coast sun, sizzled crisp and pink with sweat, gather an armload of newspapers and magazines and library books and paperback novels, and heave this bundle onto the carpet of the living room floor. My family’s ranch-style house had jalousie windows but no air-conditioning; a ceiling fan churned overhead; mosquitoes, hell-bent little fuckers, vectored in the downdraft. Their blood—my blood—blotted the spots where I smashed them.

Reading material acquired, part two of my ritual fell into place. I’d toddle into the kitchen. Ten minutes later I’d return with a sandwich, sodden with mayonnaise, cheese slices poking out like a stealth bomber’s wings, as well as vertiginous piles of potato chips and pretzels and a cold red drink made from powder mix. To this day, I find the cuboid bits of crunchy salt at the bottom of certain pretzel bags almost unholy in their deliciousness, worthy of cutting on a mirror, snorting, and rubbing on the gumline. I’d read on my stomach, chin cupped in my right hand, the pages pushed out in front of me. It was important that the food not run out before the newspapers and books did. I’d return for more chips so I could make a clean sweep of the Miami Herald sports pages. That newspaper’s sports columnist, Edwin Pope, was the first critic who mattered to me. I’d stagger back to the kitchen for a sleeve of Hydrox cookies and milk, enough to propel me through half of a crime novel by Boston’s Robert B. Parker. His hero, Spenser, was a hard guy with a soft touch in the kitchen, a rare combo platter back then. “Spenser’s the name,” he’d say, “cooking’s the game.” He tangled with bad guys yet knew his way around knobs of ginger and paws of garlic. Sometimes, too, after school, I’d flip through a skin magazine, Club or Chic or Oui, found in the weeds by the side of the road; someone no doubt had tossed it from a car window and probably regretted it later. I read these alone in my room, not eating a bite. I remember a Penthouse Forum letter in which a woman described doing things with mashed potatoes, gravy, and her grateful boyfriend that made me look at side dishes with fresh eyes.

Hermione Lee, the English biographer, has distinguished between two types of reading, “vertical” and “horizontal.” The first is “regulated, supervised, orderly, canonical and productive.” The second and more intimate variety is “unlicensed, private, leisurely, disreputable, promiscuous and anarchic.” Our real reading tends to be of the latter variety. On that living room floor, I turned from Parker, for whom I maintain a real fondness, toward more ambitious writers, the kind that slowly put me at a certain distance from my family and peers. I’d tattoo the pages with greasy fingerprints. My bouts of afternoon grazing could last three or four hours. They were irritating to my father, who like most fathers would have preferred to see his son outside in shoulder pads. I was big enough for football, but I didn’t have the nature for it. I’d be sure to finish eating and reading before he returned from work. If I heard him approaching, I’d devour the last cookie with a pelican jerk of my neck. I learned a lesson that’s crucial to misfits of every stripe: the way to keep a secret is to eat the evidence. My father did not, as the historian Garry Wills’s father did, offer to pay me to read less. In his memoir, Outside Looking In, Wills writes that he took the money and used it to buy more books.

Reading and eating, like Krazy and Ignatz, Sturm und Drang, prosciutto and melon, Simon and Schuster, and radishes and butter, have always, for me, simply gone together. The book you’re holding is a cry for help product of these combined gluttonies. While reading, I’m helpless: I always (a) wish I were also eating and (b) notice the food. In this book’s five chapters—breakfast, lunch, shopping, drinking, and dinner—I’ll walk through a day in the life of an omnidirectionally hungry human being (me), with attention paid to what writers have thought and said about what we put in our mouths and why. I’ll rely on my own perceptions, but also on those of the minds whose appetites have informed my own. Autobiography, for me, quickly edges into bibliography. The great critic Seymour Krim liked to refer to his memory as “that profuse upstairs delicatessen of mine.” It’s a phrase I’ve always loved. The upstairs delicatessen! We all have one. This book is in no small part about the contents of my own.

I’ve been happy, over time, to find confirmation that I wasn’t alone in my combinatory passion for reading and eating. Rita Dove, in “In the Old Neighborhood,” writes about how

Candy buttons went with Brenda Starr,

Bazooka bubble gum with the Justice

League of America. Fig Newtons

and King Lear, bitter lemon as well

for Othello, that desolate

conspicuous soul.

Frank Conroy, in his memoir Stop-Time, recalls lying in bed after his father’s early death “with a glass of milk and a package of oatmeal cookies beside me.” For consolation he read “one paperback after another until two or three in the morning.” Dorothy Allison’s Bastard Out of Carolina is a reminder that summer is when whole forests can fall to the buzz saw of a young person’s reading. Allison’s narrator recalls, “When school let out for the summer, I found a hiding place in the woods near Aunt Alma’s where I could camp for hours with a bag of Hershey Kisses and a book.” The critic Albert Murray described a friend who cut school to binge-read Faulkner’s Light in August, holing up “Sherlock Holmes style with it and a jug.” I’ve never nursed a jug while reading, but in high school I did find a used bookstore that didn’t mind if you sat on the floor with a six-pack between your outstretched legs and slowly ingested its contents.