If you were a newspaper photographer working in Palermo at the height of the Sicilian Mafia’s power, you had to get used to being woken up by telephone calls in the middle of the night. There’s been a murder, your editor would tell you, before giving you an address so you could rush to the scene.

More like this:

– The most iconic photos of the American West

– Photos that show landscapes few can see

– Why 1960 was a turning point for Africa

Dashing to cover a killing or a police arrest was dangerous enough, but worse was being dispatched to photograph a Mafia funeral. Unlike a journalist, who could blend into a crowd of mourners, being a photographer meant standing on the frontline, exposing yourself with your camera in front of angry family members. And when you left your assignment, you had to be cautious to make sure no one had followed you home.

Photographer Franco Zecchin remembers this life well. From the late 1970s, he worked intimately with legendary photographer Letizia Battaglia documenting the deadly gangland warfare between rival families of the Sicilian Mafia – also known as the Cosa Nostra – and the bloodshed that spilled out on to the streets of the city. The brutal period is remembered as la mattanza, Italian for slaughter.

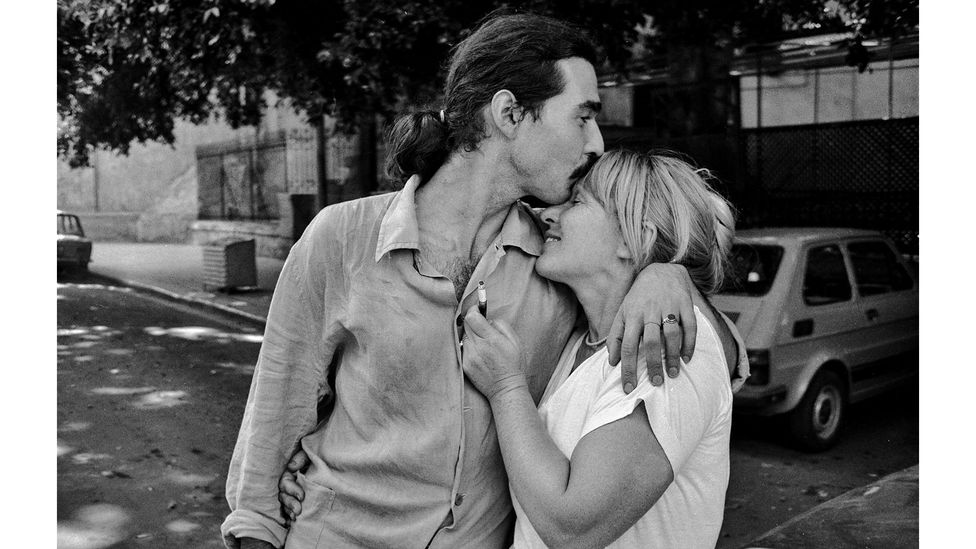

Italian photographers Franco Zecchin and Letizia Battaglia in Palermo in 1976 (Credit: Alberto Roveri/Mondadori Portfolio via Getty Images)

Zecchin and Battaglia – who died in 2022 – were also a couple, and in love. Together they organised a group of freelance photographers – mostly young people from Palermo hungry to learn the craft – to gather images for the daily, left-wing newspaper, L’Ora, which was famous for its investigations into the Mafia.

And their work was fast-paced photojournalism, so their photographic style about daily life in the city – and even the printing and processing of the images – had to be swift, in order to make the next edition. Sicily was at the centre of international press attention at the time, and the photographers had to be on call 24 hours a day. Going to the cinema meant leaving a note with the box-office attendant to alert them if they received a call from the paper.

Zecchin and Battaglia faced real physical threat – getting roughed up or having their cameras broken – and there were times when they covered five murders a day. For Zecchin, the most chilling moment came when Battaglia received a menacing, anonymous letter warning her to get out of the city immediately – and not to return.

Letter received by Battaglia warning her to leave (Credit: Archivio Letizia Battaglia – Palermo)

But Battaglia, who would go on to receive international acclaim for her work, was undeterred. “It’s a question of character,” Zecchin tells BBC Culture. “When she was convinced of something, she went in that direction without waiting or reflecting too much about the consequence.” Despite – or perhaps because of – this danger, their life together in Palermo was “an adventure”, says Zecchin.

Battaglia and Zecchin’s work is currently on display at Fondazione Merz in Turin, alongside the photography of Enzo Sellerio, Fabio Sgroi and Lia Pasqualino. The exhibition, Palermo Mon Amour, traces Palermo’s public life from the 1950s to 1992 – both the violence and quiet, everyday moments.

The head of Palermo’s police Flying Squad, Boris Giuliano, at the scene of a murder in Palermo in 1978 – he was killed by the Mafia in 1979 (Credit: Letizia Battaglia)

Curator Valentina Greco – a Palermo native – tells BBC Culture that being born in the city at this time “was to be born in a very violent period”.

And life under the Mafia continues to fascinate, with 2023 seeing the announcement of a new Mafia museum in Palermo, as well as British-Italian crime drama The Good Mothers – based on a true story of three women fighting to bring down a Mafia clan from the inside – airing on Disney+.

Palermitan children “shooting” on All Souls’ Day in 1960 (Credit: Enzo Sellerio)

Leoluca Orlando was mayor of Palermo for more than 20 years. And from his childhood onwards, he remembers the city being the capital of the Mafia.

It was “a grey city”, he tells BBC Culture, in which everyone knew about the overwhelming control of the Mafia, but no one talked about it, thanks to a strictly enforced code of silence known as omertà. The Sicilian Mafia killed more than 1,000 people between 1978 and 1983, according to one report.

The arrest of notorious Sicilian Mafia boss Leoluca Bagarella – who had murdered Giuliano – in Palermo in 1980 (Credit: Letizia Battaglia)

And because of his position, Orlando was, at times, considered to be among the “walking dead” of the city – aka, on the Mafia’s kill list. He would have to change his schedule at the last minute to avoid people finding out his location; he lived in a military barracks for a time, and once he and his family even fled to Georgia because the threat was too great.

Enough is enough

Ultimately, it was the infamous 1992 killings of anti-Mafia judges Paolo Borsellino and Giovanni Falcone that began a push for change in Sicily, Orlando says. “The people reacted and said, ‘Basta! Enough is enough!’,” Orlando recalls. “It was really an important moment.”

Thousands of students protesting against the Mafia in Palermo in 1986 (Credit: Fabio Sgroi)

Zecchin recalls the first time he met Battaglia at a drama workshop organised by famed Polish theatre director Jerzy Grotowski, before they began their work exposing the Sicilian Mafia, Battaglia had brought along her camera and was taking pictures – despite being told that wasn’t allowed. “For the character of Battaglia, this was not something that you respect,” Zecchin remembers with a smile. Battaglia simply asked: “Why?”

After someone ratted her out, Battaglia was asked to hand over her film, which she refused to do. Even though they’d just met, Zecchin came up with a plan to help her: at a shop in the nearby town, he bought a fresh roll of blank film and gave it to Battaglia, telling her to pass it off as her own. She went along with the ruse.

“This made, of course, something between us,” Zecchin says, “and after, became a love story.” A few months later, Zecchin left Milan, his hometown, and joined Battaglia in her native Palermo.

The exhibition, Palermo Mon Amour, traces the city’s public life from the 1950s to 1992 – both the violence and quiet, every-day moments (Credit: Franco Zecchin)

One of the first female photojournalists in Italy, Battaglia once called her work covering the Mafia war “an archive of blood”. Self-taught and armed with a camera and a police radio scanner, she would go on to win many awards, including the prestigious W Eugene Smith prize in 1985. In 2019, a documentary based on her life, Shooting the Mafia, was released.

According to Greco, Battaglia is “one of the icons of Italian photography, without a doubt”. But it wasn’t always easy being a couple of photographers, says Zecchin, explaining they had very different styles. While Battaglia would always seek to provoke a reaction from her subjects – “I am here, I face you, I have a camera” – Zecchin’s own style is more discreet, to “try to keep as silent as possible”.

Letizia Battaglia with a patient at a psychiatric hospital in Palermo in 1986 (Credit: Lia Pasqualino)

In the 1980s, Battaglia – who dealt with her own psychiatric issues, according to Zecchin, and often photographed patients at psychiatric institutions – went on to pursue a career in politics, serving on Palermo’s city council and in the Sicilian Regional Assembly. She hoped her political contribution could be as effective – or more – than her photography.

‘The Godfather is dangerous’

For decades, Sicily and the Sicilian Mafia have captured the imaginations of artists, writers and filmmakers. The most prominent of these, still, is Francis Ford Coppola’s 1972 crime classic The Godfather – filmed in part in Sicily – which placed second in BBC Culture’s list of the greatest American films ever made.

But while Mayor Orlando calls The Godfather and its star Marlon Brando “fantastic”, he argues that the legacy of the Coppola movie is “a tragedy for Sicilians”. By creating a message that a Mafia boss like Don Vito Corleone is a good man, Orlando argues, there is a risk that people “forget the Mafiosi are terrible, cruel criminals”.

For decades, the Sicilian Mafia has captured the imaginations of artists, writers and filmmakers, including Francis Ford Coppola who directed The Godfather (Credit: Getty Images)

Zecchin agrees, adding that The Godfather, and other films and TV shows like it, are “dangerous” in their failure to properly show the true, devastating impact on the Mafia’s victims.

For Greco, however, there is a rich world of Palermitan culture that captures the essence of life in the city, from the writing of journalist Giuliana Saladino to the films of Ciprì & Maresco.

White Lotus effect

According to Mayor Orlando, today’s Palermo has become a symbol that change is possible. While the Mafia still exists in Sicily, he says, nowadays living in Palermo “can be exciting and safe”. Indeed, as Orlando explains, Palermo’s Falcone Borsellino Airport – once a hub for Mafiosi transporting money and drugs, and journalists arriving to cover the violence – is instead now filled with tourists.

The ‘White Lotus effect’ – named after the HBO show – means it can be difficult to book a hotel room in Sicily, according to one expert (Credit: Fabio Lovino/HBO)

“Palermo is today a touristic city,” says Orlando. “It wasn’t possible to imagine that when the Mafia governed.” According to one travel expert, the “White Lotus effect” – named after the HBO comedy drama set on the Italian island for its second series – means it can nowadays be difficult to book a hotel room in Sicily.

Palermo is a city that’s been rebuilt time and time again, says Greco, “and that definitely adds to its fascination”.

“It’s a city that has a great sense of love to it,” she adds. “It was once a centre of great violence – but it’s more love right now.”

Palermo Mon Amour runs at the Fondazione Merz, Turin, until 8 October 2023.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.