EASTHAM — Eight downy ducklings tried to cross Route 6 near Nauset Road in Eastham on Aug. 1, led by a streaked brown hen. Sometime before 7:30 a.m., a car tore down the road and collided with the ducks, killing the mother hen. The car, according to the Eastham police, sped away.

The ducklings, leaderless in the middle of the highway, started panicking and running around frantically. When officers arrived on the scene, they rounded up the chicks and took them to Wild Care, the wildlife rehabilitation center in Eastham.

At first, the ducklings seemed to perk up with hydration. They were placed alongside Wild Care’s resident female mallard, Mallory, according to Stephanie Ellis, the organization’s director. But the incident proved too stressful for some of the young birds. After a few days, four of the eight ducklings had died. The four that survived were released into the wild after a few weeks of care.

It’s easy to become desensitized to roadkill here. Route 6 is littered with the bodies of animals that tried crossing at the wrong moment, and some back roads are no less lethal. But roadkill and road injuries can affect our wild species’ populations. And with the right precautions, many collisions with animals can be prevented.

Turtles, Toads, and Mammals

There are no formal data on how many animals are struck by cars on the Outer Cape. But the number of road-injured animals at Wild Care suggests it is a significant problem: last year, the organization took in 152 animals that had been struck by cars. That is nearly 10 percent of the animals brought in for care — from all over the Cape.

Even in the late fall, the center is full of road-injured animals being rehabilitated. A Canada goose found with a head injury on Chequessett Neck Road in Wellfleet. A snapping turtle run over by a car in East Falmouth. A sharp-shinned hawk found sitting on a roadway in Dennis.

Many of the road-injured animals that arrive at Wild Care die from shock and other immediate effects of the collision. But if they survive the initial incident, they stand a decent chance of being successfully rehabilitated. Ellis reported that approximately 60 percent of road-injured animals brought to Wild Care that survive the first 24 hours are later released into the wild.

For some species in particular, roadways present an existential threat.

Turtles, for instance, are slow-moving and often need to travel away from their usual habitats to lay their eggs. This behavior can force them to cross roads, and 40 percent of all reptiles at Wild Care — mostly turtles — were struck by cars.

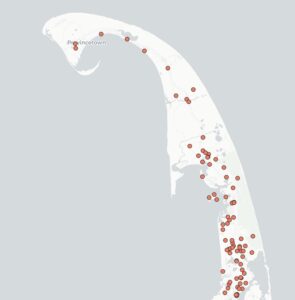

For diamondback terrapins and Eastern box turtles, these injuries and deaths are especially problematic because both species are threatened, and nearly all the turtles that are struck are females that are traveling to lay eggs, according to Ellis. She called the back roads of Eastham a “danger zone” for terrapins.

One problem, according to Ben Goldfarb, author of Crossings: How Road Ecology Is Shaping the Future of Our Planet (W.W. Norton, 2023), is that roads are often built close to water and in flat low-lying areas. “Those are also the same places that wild animals like,” he told the Independent.

These roads are especially dangerous for amphibians like toads and frogs. Many amphibian species migrate — and cross roads — in large numbers to reach vernal pools and upland breeding sites, which can lead to what Goldfarb calls “mass squishing events.” One such event happened on the Outer Cape in 2005, when 1,200 Fowler’s toads were killed on a 1.5-mile stretch of road in North Truro in a single night. The mass squishing was reported in the Journal of Herpetology.

When larger carnivores like coyotes, foxes, and bobcats become roadkill, their populations also suffer because these animals take a long time to mature and reproduce, Goldfarb said.

The bobcat found dead on the side of Chequessett Neck Road in Wellfleet last winter was the first sighting in town in centuries. The autopsy revealed that it was a female.

“These mortality events aren’t just inconveniences,” Goldfarb said. “There’s literally nothing that we do on this planet that kills more wild animals on land than drive.”

Gardens, Tunnels, and Speed

Despite an apparent abundance of road injuries and mortalities on the Outer Cape, there are measures that can prevent these incidents. Ellis recommends putting up more signs to slow drivers at places known to be wildlife crossings.

Goldfarb advocates constructing wildlife crossings, which are essentially large bridges of habitat paired with road fencing that allow wildlife to pass over dangerous roadways. While their effectiveness depends on their placement and design, at least one assessment suggests they can reduce roadkill significantly, according to a National Public Radio story on the problem.

The construction of “turtle gardens” is helping diamondback terrapins in Wellfleet. These are patches of sand between the roadway and the salt marsh that present terrapins with perfect nesting habitat, encouraging them to lay their eggs without crossing roadways. Mass Audubon’s Wellfleet Bay Sanctuary staff and volunteers have constructed a number of these gardens as part of its terrapin protection program and are seeing this species rebound here.

“Amphibian culverts” are another solution. Because frogs and toads migrate along predictable paths each year, a well-placed series of passages can allow these creatures to cross underneath roads safely. A collection of tunnels like this was installed in Amherst in 1987 to help spotted salamanders cross roads, and at least one study has found that the strategy worked.

Another study on Fowler’s toads on the Outer Cape suggested periodically closing some roads in the National Seashore at night during peak migration season to avoid road mortalities. The towns of Keene, N.H. and Brunswick, N.J. have instituted closures of this kind during the first warm rainy spring nights to ensure their amphibians can safely cross the road.

On an individual level, Ellis said, the best mitigation measure is simply driving more slowly and carefully, especially at night when animals tend to be more active. Goldfarb, too, recommends driving cautiously on warm, rainy spring nights when amphibians are apt to be out and about.

“Cape Cod is a place that is just teeming with wildlife,” Ellis said. “So slow down.”