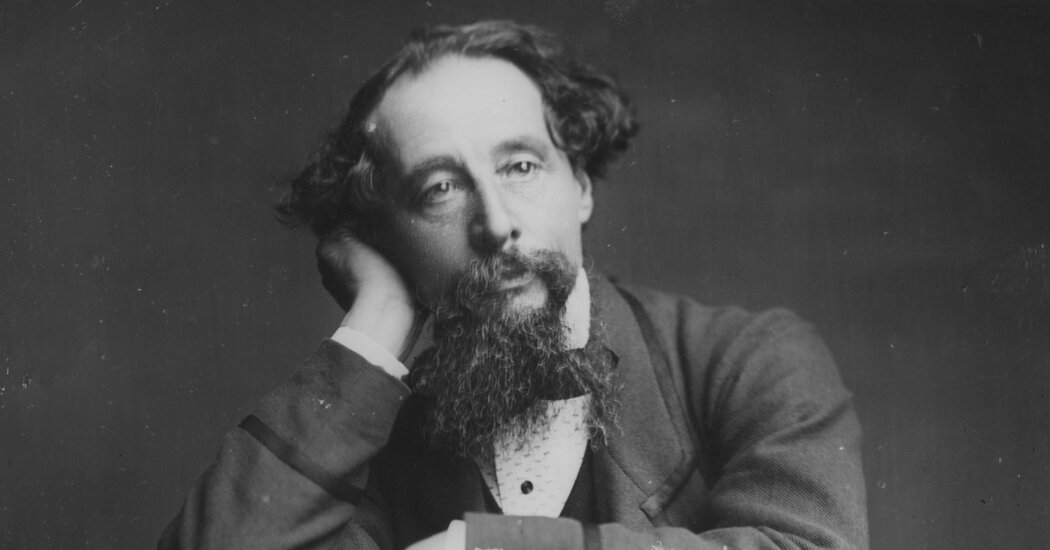

THE LIFE AND LIES OF CHARLES DICKENS, by Helena Kelly

The specter of biography has long struck fear in the hearts of living legends. Martha Washington, Henry James and Somerset Maugham tried to thwart would-be chroniclers by pitching private papers into the fire — heartbreaking acts of futile resistance. Trusted correspondents did not, as James instructed, “burn, burn, burn.”

Charles Dickens, however, had a much happier outcome in his friend John Forster’s three-volume biography, published between 1871 and 1874. The trouble, according to Helena Kelly’s new book, “The Life and Lies of Charles Dickens,” is “simply that Forster wasn’t a very good biographer.”

For decades Forster, a writer and critic of comparatively modest success, was kind of like Dickens’s literary companion. He listened to Dickens’s troubles, read his rough drafts and negotiated much of his life, including a marital separation from Catherine Hogarth, the mother of his 10 children, whom he left for Ellen “Nelly” Ternan, an actress 27 years his junior. It was the first time Dickens — who was “astonishingly, globally famous,” Kelly writes, “a product, a brand” — suffered in the public eye.

And before he died, in 1870, Dickens entrusted Forster with his manuscripts. Ever the “faithful assistant,” Forster copied down “the story Dickens gave him,” and published the first volume of “The Life of Charles Dickens” 18 months after his subject’s death, which is the best time to make hay.

A century and a half later, archives are far more accessible than they used to be, and Kelly is ready to try “Dickens the conjurer” for a book that amounts to “posthumous brand management.” Among a laundry list of perjury charges is Forster’s biggest revelation: that the novel “David Copperfield” was semi-autobiographical, inspired by Dickens’s childhood labor in a boot-polish factory during his father John’s (first) stint in debtors’ prison. Dickens, who wrote his own press releases, had managed to suppress the most basic facts about his background; now readers had Forster to “confirm” what they’d suspected all along.

“The picture of the young Charles as an inexplicably neglected child laboring forlornly in a warehouse by the river while his father languishes in the Marshalsea prison is terribly affecting,” Kelly writes, “but can we be sure that it’s accurate?” This is not a new question — nor is it one the author ultimately answers. In an 1872 issue of The North American Review, a critic called the fib “a good example of this peculiarity of Dickens’s character, and of Mr. Forster’s apparent inability to detect it.”

In fact, many of the inconsistencies, omissions and outright lies Forster parroted have since been corrected and refined; and Kelly — an Oxford Ph.D. whose previous book was “Jane Austen, the Secret Radical” — is noticeably ungenerous with her citations, which mostly include 19th-century sources, conspicuously omitting the generations of scholars who’ve come before her to illuminate Dickens’s dishonesties.

When Kelly unleashes her inner literary critic, she delights readers with pages upon pages illustrating the enduring influence of Dickens’s fictional biography on his fiction: The prisoner John Barsad returns to his family in “A Tale of Two Cities”; the orphan Esther Summerson buries a doll that is a vestige of her former life in “Bleak House”; the titular “Little Dorrit” is born and raised in Marshalsea.

Positioning herself as a truth-teller — “Inconvenient facts keep looming out of the fog,” she writes; “there’s little ground that will bear any weight” — Kelly has no qualms about extrapolating her own unsubstantiated theories from Dickens’s textual clues. Based on her extensive knowledge of Victorian-era ailments, Kelly suspects that the author had syphilis and that, like “the guilt-ridden men who appear in his last novels,” he passed it to his unknowing family, including Catherine, one child who died in utero and another, Walter, who died suddenly at 22. “Proof? No, not that,” Kelly admits. “This is a theory.”

Her title suggests she is out to raise hackles, and if she succeeds, it likely won’t be in the way she intended. In the grand tradition of biography, Dickens’s offenses are middling. And when it came to his own work, he spent a lifetime reimagining and repurposing his personal experiences into fictional narratives — which is what storytellers do.

Speaking of his fiction, when it comes to literary analysis, Kelly isn’t just unimpeachable — she’s energizing. For the first time in years, I’m excited to revisit “David Copperfield” and “Oliver Twist.” I can picture Dickens scholars passing their big, bold but timeworn questions like a baton, which is an achievement in itself.

THE LIFE AND LIES OF CHARLES DICKENS | By Helena Kelly | Pegasus | 272 pp. | $29.95