I.

For a week in 1980 and five months in 1981, I worked for the controversial Polish American novelist Jerzy Kosinski. He wasn’t controversial then. Brilliant, charismatic, fawned on by New York’s upper crust, he was, at 47, at the peak of his storybook ascent. His third novel, Being There, had just been made into an award-winning film starring Peter Sellers, and Warren Beatty had cast him to play a major role in Reds. No one could have foreseen the nightmare that lay just ahead for him.

He called me on November 28, 1980, to ask if I would read the final galleys of his latest book. I didn’t know him or his work, so I said if the book was in final galleys, I would suggest leaving it alone. “I can’t,” he said in a high-pitched voice with a strong Slavic accent. “It came out seven years ago, but I was never satisfied with it. It’s a very personal story, so I’ve got to get it right this time. I promise it will only take you a few days.”

He sounded so likable that I yielded: “How about if I spend an hour or two looking at a couple of the galleys and tell you what I think?”

“Perfect!” he said. “Can you come to my apartment tomorrow?”

The apartment was high up in a building at the corner of Sixth Avenue and 57th Street.

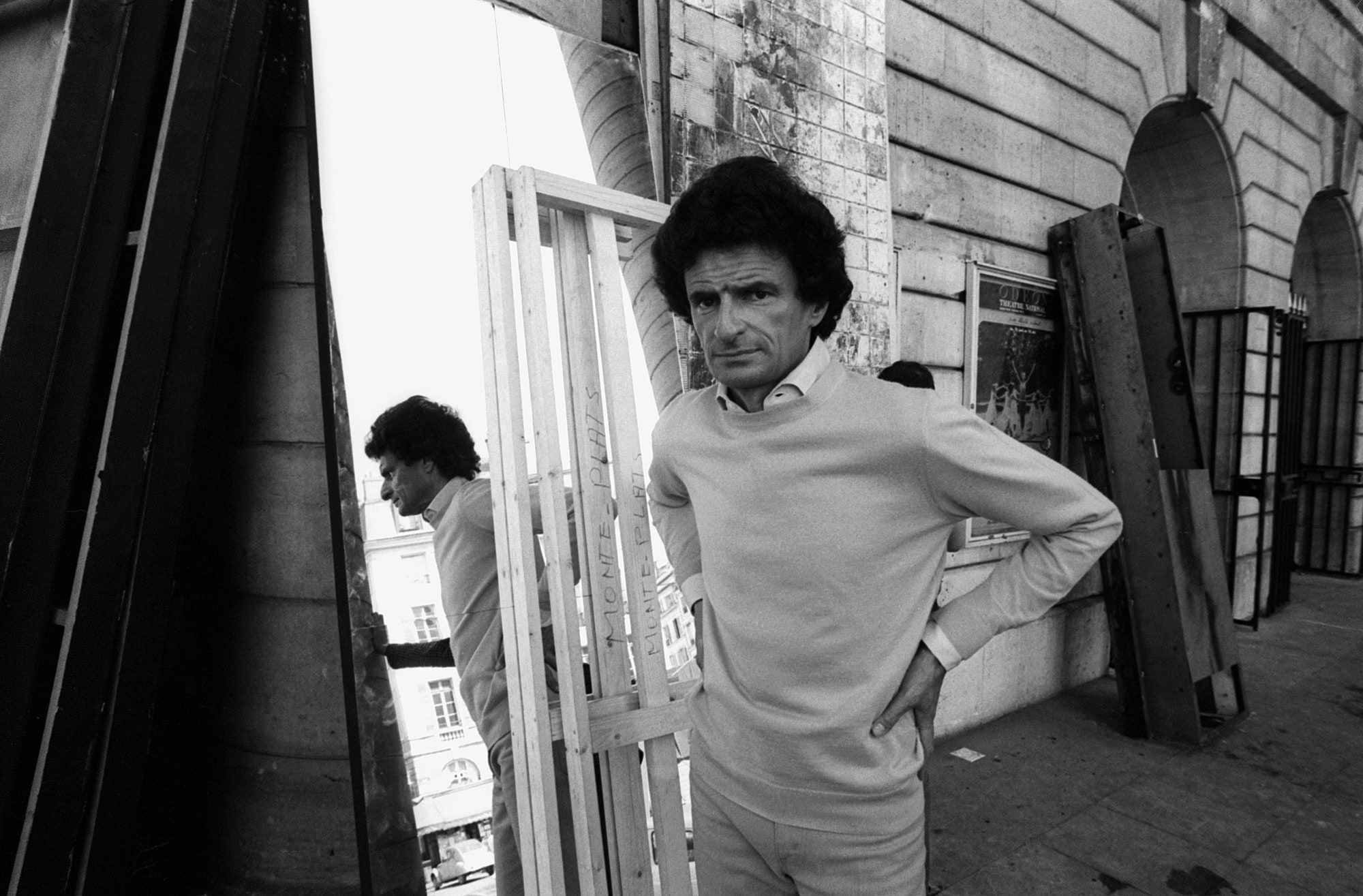

A tall, auburn-haired woman answered the door and introduced herself as Kiki von Fraunhofer. “Come in, come in!” called Kosinski from the room behind her. Thin and wiry, with piercing eyes, a nose like an eagle’s beak, and a mass of black curls, he had star quality. He was standing in front of a large window beside a table with a stack of galleys on it.

After hurried introductions, he said, “You’ll sit here if that’s okay. Kiki works there,” he continued, pointing to a table with a typewriter on it in the kitchen area. “I work back there,” he added, gesturing in the opposite direction. “Kiki will get you anything you need.”

I was struck by the modesty of the place: one large room furnished with two brown tufted leather couches, a coffee table between them, and a couple of straight-backed chairs; to one side a small kitchen, to the other a bedroom alcove and a bathroom.

The galleys were anything but final, sprinkled with the sort of errors made by writers whose first language is not English. I assumed—correctly—that Kosinski had read the previous galleys and introduced mistakes. I could also tell, however, that he was highly intelligent and totally original, and his spoken English was smooth and fluent.

After two hours von Fraunhofer took my marked galleys to Kosinski. Minutes later, he swept in, beaming. He said my changes were just what he had hoped for, and would I please, please come back and finish the job. The novel was called The Devil Tree.

Kosinski wore pajamas when he worked. At 11:30 a.m. we ordered sandwiches and salads from Wolf’s Delicatessen across the street, and he joined von Fraunhofer and me for lunch at my table. He was a wonderful, witty raconteur.

I soon learned his astounding history—at least his version of it. Born Józef Lewinkopf to well-off Jewish parents in Łódź, Poland, in 1933, he would almost certainly not have survived the Holocaust if his father had not changed the family’s name and farmed out his six-year-old son to peasants in the countryside for safekeeping. In their care, the boy was cruelly mistreated, once so traumatically that he lost the power of speech for six years. Reunited with his family after the war, he earned two MA degrees from the University of Łódź and taught at the Polish Academy of Sciences. He also studied in the Soviet Union—he spoke Russian and German—and served in the Polish Army Reserve.

In 1957 he managed to immigrate to America, where he taught himself English, worked on a PhD at Columbia University, and received grants from the Guggenheim Fellowship and the Ford Foundation. He then taught popular courses at Wesleyan, Princeton, and Yale. Under the pseudonym Joseph Novak, he published two very critical books about life under Communism, The Future Is Ours, Comrade (1960), and No Third Path (1962).

In 1962 he married Mary Weir, the widow of a Pittsburgh steel tycoon, who was older than he and who, as long as she lived, had the benefit of her late husband’s fortune. With her, Kosinski enjoyed great luxury—a yacht, expensive cars, grand tours, multiple residences. He also became an American citizen and published his first novel, The Painted Bird, a fictionalized account of his tortured childhood, which won him international praise except in Poland, where his books were banned. Weir died in 1968, by which time Kosinski had begun his relationship with Katherina “Kiki” von Fraunhofer, who came from an aristocratic Bavarian family. During their time together, he had produced six more novels, most of them dedicated to her.

The first of these, Steps (1968), won the National Book Award. Kosinski’s screenplay for the second, Being There (1971), won the top award from the Writers Guild of America and the British Academy of Film and Television Arts. The film won a best-supporting-actor Oscar for Melvyn Douglas in 1980, and Kosinski was a presenter at the Oscars in 1982. The original The Devil Tree (1973) was followed by three less successful works, all containing people and incidents drawn from Kosinski’s life and more and more heavily laced with explicit sex scenes: Cockpit (1975), Blind Date (1977), and Passion Play (1979). By then world sales of his books were in the millions, and from 1973 to 1975 he was president of the American branch of PEN, the international writers’ association.

He came along at a propitious moment in time, when a crop of colorful New York writers started to be treated as celebrities in the media. Elaine’s, a restaurant on the Upper East Side owned and managed by Elaine Kaufman, became the favorite gathering place of these writers, who sat shoulder to shoulder at their special tables—Norman Mailer, Mario Puzo, Kurt Vonnegut, Gay Talese, and Tom Wolfe, to name a few. Even alongside those stars, Kosinski seemed special. He was a frequent guest on TV of Johnny Carson and Dick Cavett and the life of the party with such exalted friends as Henry Kissinger, Zbigniew Brzezinski, Oscar de la Renta, Diana Vreeland, Mike Wallace, Tony Bennett, and Ahmet Ertegun. Known for his playful stunts, he was apt to arrive at social events disguised with a wig or a false mustache, and he liked to find a hiding place and disappear for hours.

He and I connected nicely—we were almost the same age—and I enjoyed working with him, always knowing that he would have the last word. Once, I got him to add a paragraph to the text, suggesting that he might spell out more clearly the moment his rich young hero decides to cast off his powerful advisers. That night Kosinski phoned me to say he was taking my advice. He had written a connecting paragraph, which he read to me. It appears late in the book and begins “Soon after that Whalen was sure that the time had come for him to forge his own covenant.”

When we finished the edit, he said he would be starting the next novel soon and hoped I would be available.

II.

The new novel, Pinball, has two heroes: the country’s top rock star, who conceals his identity, and an older musician, who sets out to unmask him. We worked from nine to five, Monday through Friday. Kosinski composed in the bedroom and von Fraunhofer retyped a few pages at a time; I edited the text, and she returned it to Kosinski, who kept what he wanted. Each page came back to me at least two or three times.

One day Kosinski pointed to a sentence I had altered and said, “You don’t want to change this. It’s a wordplay.” Turning words around on themselves was his Achilles’ heel. I told him wordplay has to make sense or it doesn’t work, but showing off his English had obviously become a feature of his social discourse; I could just hear Kissinger or Vreeland complimenting him on how deft he was at it. In this case he accepted my edit, but I could never stop him from trying to overstretch the language. (An example from Passion Play: A character says of illegal Haitian immigrants, “Remember, only a week ago they were starving in Port-au-Prince.” A second character then says to the hero, “Now you could be the prince of their port.”)

We finished on October 17, five months after we started—a record for him. At some point he began presenting me with his novels, all playfully inscribed, until I had the entire set. As I was leaving one evening, von Fraunhofer told me Kosinski would like to hire me on a permanent basis. They planned to spend several coming months in Europe, she said, and I would of course travel with them.

By then, however, I had had several interviews for a job at The New York Times Book Review. When Kosinski heard that, he told me, “Abe Rosenthal [the executive editor of the paper] and Arthur Gelb [then the deputy managing editor] are great friends of mine. Do you mind if I call them and recommend you?”

III.

When I started at the Book Review, on October 19, 1981, I had no inkling that Kosinski was under ongoing attacks in the Polish press, with claims that his books in English had been written in Polish and translated by others without credit and that he had stolen the plots of The Painted Bird and Being There from Polish writers.

On my second or third day, Arthur Gelb phoned me. He said his wife was writing a cover story on Kosinski for the Times magazine. Could she call me? Minutes later I was on the phone with Barbara Gelb, who basically wanted to be assured of just one thing: that Kosinski did not need any serious help with his writing. I had to disabuse her by saying that he required the kind of help most second-language writers require.

Her lengthy article, “Being Jerzy Kosinski,” with a cover photo by Annie Leibovitz of the novelist in polo jodhpurs, stripped to the waist, appeared on February 21, 1982. It was a pure puff piece, pegged to the publication date of Pinball. Gelb briefly describes Kosinski’s writing process: “He knows precisely how to use his time: so many weeks allotted…to the writing, the typing, the editing, the correction of galley proofs, the promotion tour.” She leaves the rest to von Fraunhofer: “And the woman who mothers him also acts as his business manager, his secretary-typist, proofreader, housekeeper, traveling companion (he is always on the go and claims he can write anywhere), fellow polo player and skier.” No mention of hired help.

Gelb touched lightly on Kosinski’s critics:

If that was Kosinski’s treatment at the Times magazine, however, there was an entirely different one in store at the Times book review. Each week the editors met to determine which books should be reviewed. At one early meeting I attended, Harvey Shapiro, the editor in chief of the book review, called on Robert Asahina, one of the young editors: What books did he want to bring up? Asahina said he had looked at Kosinski’s new novel and would strongly suggest that we pass on it. Shapiro turned to me: “Isn’t that the one you worked on? What do you think?” I said I had a personal stake in it; nevertheless, I thought it would be a mistake not to review a Kosinski novel. Professors all over the country taught his books, and he had an enormous international audience.

On February 25, the daily paper ran a review by Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, which began:

I had no recollection of limpid in the manuscript, but if the critic had only known to look, he would have found it correctly used on page 197 of Passion Play, Kosinski’s previous novel: “a privileged intimacy as limpid and inevitable as a forest brook.”

Lehmann-Haupt drove on: “Lacking a sense of the language, and thus lacking any style of his own, the author gropes for any passable cliché.” Kosinski and I had not stayed in touch after I stopped working for him, but I could imagine how this review must have stung, coming from the same paper in which, in 1968, the critic Hugh Kenner had written about Steps, “Céline and Kafka stand behind this accomplished art.”

IV.

Richard Locke, the deputy editor of the Times book review, interviewed me for my job, but before I started, he had gone to Condé Nast to edit the soon-to-be-relaunched Vanity Fair. Seven months later he invited me to join his staff. No sooner had I moved to the Madison Avenue office than I had a request from two reporters at The Village Voice to be interviewed about Kosinski. After my experience with Barbara Gelb, I declined. But Locke, urged on by several of his senior editors, told me I really must speak to these men—this was serious stuff.

So I spoke to one of them by phone, and it was crystal clear that all he wanted from me was the assurance that I played a big role in creating Kosinski’s fiction. I told him what I had told Gelb, with the same result: I was not mentioned in the lengthy article by Geoffrey Stokes and Eliot Fremont-Smith that appeared on June 22, 1982, titled “Jerzy Kosinski’s Tainted Words.” If Gelb had produced the consummate puff piece, these men came up with the ultimate hatchet job, charging: “For almost 10 years now, Jerzy Kosinski has been treating his art as though it were just another commodity, a widgit [sic] to be assembled by anonymous hired hands.”

Gelb had unwittingly provided the Voice writers with a second target: The New York Times itself, generally considered to be the temple of thorough, unbiased journalism, the last word. These downtown reporters were able to refer sneeringly to Gelb’s article as “the adulatory profile in the Times magazine,” and they showed up her gushing appraisal of Kosinski with relish.

They had interviewed, besides me, a number of Kosinski hires, who provided them with some eye-popping quotes. In the story, Richard Hayes, a former professor of drama at NYU and Berkeley who had worked on Passion Play, recalled: “I would say instead that I combed, fileted, elevated or amplified his language—that I invested it with a certain Latinate style which was sometimes more Hayes than Kosinski.” Here is an example of that style, on page 35 of the hardcover:

John Hackett, a professor at the University of Texas, took offense at the suggestion that he was hired to proofread Cockpit: “I was at that time an assistant professor of English and Master of East College at Wesleyan. I was not the sort of person you would hire as a proofreader.”

Barbara Mackay, an assistant director at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts who had met Kosinski when she was a graduate student at Yale and worked on four books with him—Being There, the original edition of The Devil Tree, Cockpit, and Blind Date—explained:

The Voice writers had two other crimes to charge Kosinski with: He probably wrote The Painted Bird in Polish, not English, and his nonfiction books might have been sponsored by the CIA. They interviewed a woman who said she had been asked by Kosinski to translate the novel. Their account was vague at best: “Early in 1973, one Halina Bastianello, a translator, wrote a letter to a New York Times reporter, claiming that some years earlier she had answered an ad for a Polish to English translator placed by Kosinski in the Saturday Review, and that he had wanted to hire her as the translator for The Painted Bird.” The writers couldn’t pin the story down, however. The Times had never followed up on it, Kosinski’s recollections in his interviews with them seemed to conflict with Bastianello’s account, and the Saturday Review’s records of the period were not sufficient to settle the issue.

Neither could they prove that Kosinski’s two early nonfiction books had been fostered by the CIA, given that organization’s well-known lack of transparency. Nevertheless, they ended the article on a tone that is both minatory and condescending:

One wonders how sorry these two really felt for someone who had survived the Holocaust, won a National Book Award, written the Oscar-nominated screenplay for an award-winning movie, played a major role in another award-winning film, and taught at Wesleyan, Princeton, and Yale. In the end, it didn’t matter. They had managed to get an angry quote out of their subject that would do him in. They put it in italics at the head of the article:

V.

Stokes and Fremont-Smith indicated that they planned to report further on the Kosinski matter, but they never did, presumably because they didn’t have the goods to pursue their arguments to a reliable conclusion. But their loud cannon shot caused irreparable damage. Papers and magazines all over the globe felt obliged to join in the Kosinski debate, and that kept the accusations alive for years.

The Voice reporters were roundly attacked by Kosinski’s publishers, his fans, and his powerful friends. Even the Kosinski hires they had quoted, with one exception—Richard Hayes—complained that they had been misquoted or misinterpreted.

It took four and a half months for The New York Times to enter the battle, but when it did, on November 7, 1982, it was with a 6,400-word article on the front page of the Arts and Leisure section—the longest ever to run there. Originally assigned to Michiko Kakutani, a rising star at the paper who soon declined the job, it appeared under the byline John Corry. Friends at the Times told me the piece was edited by Abe Rosenthal personally, and Arthur Gelb provided the title: “17 Years of Ideological Attack on a Cultural Target.”

Corry set out to dismiss the Voice reporters as mere perpetrators of old rumors about Kosinski planted in Poland after he published his two anti-Communist books. The principal spokesman for those rumors was Wieslaw Gornicki, who in the 1960s had been a correspondent at the United Nations for the Polish Press Agency and who then was a government adviser in Warsaw. In 1969 he wrote, “Jerzy Kosinski is the biggest literary fraud in the last several years. You cannot separate the writing of this man from his gigolo extravaganzas, his blackmails and his cheats.” He claimed that “every émigré child knows that it is not Mr. Kosinski who writes so well in English, but a man called Peter Skinner—an authentic Englishman with an Oxford education, who has been hired as a ghost writer.”

The Voice reporters hadn’t found, or didn’t quote, Skinner, but the Times trumped them by doing both:

Corry let Kosinski himself respond to the Voice’s charge that the CIA “apparently played a clandestine role” in the publication of his first two books:

Corry managed to catch the Voice writers in a stupid mistake, which by coincidence arose out of their effort to discredit Barbara Gelb, who had written:

Jumping on that, the Voice responded:

Corry calmly asserted:

The Times called the very originality of the Voice article into question. Corry reported that Kosinski phoned Victor Navasky, the editor of The Nation, after he heard that magazine was preparing a story on him. It was not true, Navasky told Corry, but Kosinski’s call aroused suspicion, so Navasky assigned a writer to investigate. When word of that got around, Navasky added, The Nation got many calls. “Among the callers, Mr. Navasky says, was Eliot Fremont-Smith…who wanted to know what The Nation had heard.” Corry continued: “The Nation’s story was dropped, Mr. Navasky says, when the writer assigned to do it lost interest.”

It would seem that Corry had settled the matter for good, but the length and tone of the Times article smacked of obvious overkill. The mud the Voice had flung—verified or not—stuck. Kosinski ceased to be a superstar. He was now a writer permanently under suspicion.

He spent nearly a decade out of the limelight, no longer even the bad boy who flaunted his familiarity with the city’s sex clubs, because they had been closed by the AIDS epidemic. He and von Fraunhofer spent more and more time abroad. They were rarely mentioned in the gossip columns, until February 15, 1987, when they were married in the apartment of the socialite Marian Javits, with only 28 friends in attendance, including the Rosenthals, the Gelbs, the Brzezinskis, and the Erteguns.

Kosinski labored five years on his next book, which was postponed again and again. He also reportedly had a string of affairs with younger women. I was at a party one night when his name came up. “I see that writer Jerzy Kosinski in my building every day,” a young woman volunteered, adding, “His girlfriend has the apartment below mine.”

VI.

One day in 1985, Kosinski came to Vanity Fair to pitch an idea to the director of photography, Elizabeth Biondi, who asked me to sit in on their meeting. Kosinski had always identified himself as a photographer as well as a writer. In 1976, he said, his friend Jacques Monod, the French Nobelist biochemist, learning that he had only a short time to live, had invited him to document his dying. Kosinski was proposing a photo essay of Monod’s final stages.

The Voice and Times articles were still much talked about in the publishing world, but since there was a third person with us that day, Kosinski and I avoided any mention of them. He was not the man I knew, however; the flair was gone, along with his biting sense of humor. That was the last time I saw him.

Tina Brown, then Vanity Fair’s editor, declined the photo essay, which was published in Esquire in March 1986. In 1988, Brown assigned Stephen Schiff to write a Kosinski profile for the June issue, pegged to the publication of his long-delayed novel, The Hermit of 69th Street. I remember lending Schiff my copy of The Painted Bird, but I recused myself from taking part in the article, which was called “The Kosinski Conundrum.”

Kosinski gave Schiff a generous amount of time, but it seems as if in return Schiff gave the novelist an easy ride. He repeated without question Kosinski’s accounts of his awful childhood and his marriage to Mary Weir. When he asked Kosinski to explain how he got out of Communist Poland to come to America, Kosinski snapped, “I’m not going to tell you my life. No. I write fiction. I don’t write biography.” He brought that line of questioning to an end by saying, “Look, I came to America in such a fashion that the only way to secure the future of those who helped me was to maintain that sort of a fiction.”

Schiff devoted paragraphs to Hayes and the Latinate flourish he brought to Passion Play, only to conclude, “The result was [Kosinski’s] worst book ever—a two-headed monster, born babbling infelicities.”

The story Navasky told Corry regarding The Nation’s part in the Kosinski war was filled out by Schiff:

Pochoda left The Nation to be one of Locke’s senior editors at Vanity Fair.

VII.

The Hermit of 69th street: The Working Papers of Norbert Kosky is not for readers unfamiliar with Kosinski’s life and work, because virtually every sentence is self-referential. The book is an encyclopedic document devoted to vindication and revenge. Kosinski is determined to prove to his enemies that he can produce a novel as original and erudite as Ulysses, in an English to match Joseph Conrad’s. Even for readers who are familiar with his work, Hermit is therefore a fatiguing slog rather than the dazzling work of art he hoped it would be.

The hero, Norbert Kosky, whose found papers have been entrusted by his estate to the writer Jerzy Kosinski, is also a Polish Jew, a survivor of the Holocaust, 55 years of age, with eight novels and a screenplay behind him. He is hounded by two evil writers trying to prove that he is a fraud who gets an unconscionable amount of editorial help with his writing. The 529-page text is peppered with thousands of boldface quotes by famous individuals, beginning on the first page with one by Albert Einstein and concluding with one by Thomas Wolfe, one of many authors Kosinski cites as being charged with excessive assistance in their writing, among them Balzac, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and James Fenimore Cooper. The book is further weighed down by more than 650 footnotes, ranging from the smart-alecky to the painfully pretentious. Much of the endless wordplay in the novel springs from a totemic use of the initials SS (or two words together starting with s) and the number 69.

A few samples:

Here, note Kosinski’s pinpointing of the word limpid:

Here, he obliquely attacks those who use his creative license against him:

The novel ends with Kosky’s death at the hands of four nameless men who pursue him in the dark, beat him senseless, then swing him by the hands and feet, hammock-style, and throw him into New York’s East River—the same way enraged peasants throw the boy hero of The Painted Bird into a pit of human excrement.

Bantam, the publisher of Pinball, rejected the manuscript. It was published in 1988 by Seaver Books, a division of Henry Holt, to generally negative reviews. Years later I was at a small dinner party with the imprint’s founders, Richard and Jeannette Seaver, and I asked them what had gone wrong. Jeannette responded that everything would have been fine if she could have kept Kosinski from making changes on the final galleys.

In the early morning hours of May 3, 1991, Kosinski, who was 57, swallowed a lethal dose of pills, got into his bathtub, and tied a plastic bag over his head—a suicide recommended by the Hemlock Society and described by him in his final novel. Von Fraunhofer, who was asleep in the next room, found him hours later, along with a note he had left: “I am going to put myself to sleep now for a bit longer than usual. Call the time Eternity.”

The reason he took his own life was variously explained in the press, from his long-standing heart problems to—according to his Polish friend Czeslaw Czaplinski in an interview with Vanity Fair’s Anthony Haden-Guest—an increasing forgetfulness and thus a fear of Alzheimer’s. But many who knew him well, among them Abe Rosenthal, attributed it to his deep depression.

VIII.

In March 1996, Dutton published Jerzy Kosinski: A Biography by James Park Sloan, a novelist and professor of English at the University of Illinois in Chicago, who says he and his subject were friendly for 20 years. His acknowledgments reveal that he interviewed more than 100 people who knew Kosinski, in Poland and the US.

The book answers many questions its subject always dodged. For instance, Kosinski was never separated from his family during the war; they were all hidden in open view under their new name in rural villages by sympathetic Catholics. They attended Mass, and Jerzy received First Communion, but he had to stay close to their dwelling, because local boys threatened to undress him and expose his circumcised penis. He ultimately dealt with his fear by turning it into fiction, but he always declined to deny that he was the boy hero of The Painted Bird. The cover of the second edition shows a boy’s face over a collection of Brueghel-type creatures; we learn from a photo section in Sloan’s book that it is taken from a photo of Kosinski at age six. Sloan also makes clear that the two nonfiction volumes and The Painted Bird were all translated from Kosinski’s Polish.

Sloan says that Mary Weir’s young husband exaggerated her wealth by many millions even as he played down her age (she was 18 years older), their divorce after four years, and the fact that she was a hopeless alcoholic, in and out of clinics.

Sloan reveals that Kosinski’s relationship with Kiki von Fraunhofer, if it was ever passionate, did not remain so for long. A notorious kinky-sex addict, Kosinski admitted to friends that Kiki was not his type, that he had married her mainly to repay her for 25 years of limitless devotion. Sloan adds that Kosinski started discussing a divorce soon after they wed, and that he was planning to move to Florida with his latest love, the 47-year-old Polish singer Urszula “Ula” Dudziak, when he committed suicide.

Sloan relates how one night in December 1990, two journalists led Geoffrey Stokes from a bar in Greenwich Village to a nearby restaurant where Kosinski was eating. Stokes was very nervous, but Kosinski was quite contained as he said, “You ruined my career.” Stokes replied that Kosinski could have avoided the whole ordeal if only he had come clean with Fremont-Smith and him. Kosinski responded: “You don’t understand. All my life I’ve been hiding.”

The biographer contacted most of Kosinski’s hired editors; he even includes a new name, Maxine Bartow. He didn’t talk to me, perhaps because I was never mentioned by Kosinski’s friends or his foes. His final assessment of Kosinski’s work seems fair and correct:

The New York Times ran two reviews, by Christopher Lehmann-Haupt and Louis Begley.

Lehmann-Haupt, who 14 years earlier had laid such stress on the word limpid in his review of Pinball, ended his review of the biography with a strained concession:

Begley, while complaining that the biography is too gossipy, took the opportunity to eloquently sum up Kosinski’s predicament as a writer:

IX.

I know I’m Zelig in this story. But because I once worked with Kosinski so closely and liked him, I never cease to be moved by his tragic fall. With 40 years’ hindsight, I’m happy I was not quoted by Kosinski’s attackers in the Voice, who went off half-cocked and inflicted immeasurable pain, or by his buddies at the Times, who in their obvious attempts to turn him into an unblemished superman only cast more doubt on him.

As for the editors hired by Kosinski, in their various depictions of what they did, they seemed to forget what they were hired and paid to do—smooth out his prose without taking public credit for it. Maxwell Perkins would never have hoped to have his name on the cover of Look Homeward, Angel. Ezra Pound would have been appalled to be thought of as the cocreator of The Waste Land. The Painted Bird and Steps and Being There, as well as his later works, are Kosinski’s legacy and no one else’s.

Frightened always by the fear of discovery of the facts he concealed in his novels, Kosinski probably hired more helpers than he needed. One mentioned by Sloan, Maxine Bartow, I met in Nyack 15 years ago, when she was introduced to me by a mutual friend as someone who had also worked for Kosinski. I called her recently to say I was writing this article, and I asked her if she ever spoke to the writers at the Voice and the Times. “Michiko Kakutani called me,” she said. “She kept asking if Jerzy wrote his own books.”

Bartow and I spoke at length about working with Kosinski—how funny and generous he could be. She said he even paid for her parking in Manhattan when she drove in on weekends from Nyack.

“Did you work only weekends?” I asked.

“Yes.”

“What books did you work on?”

She mentioned The Devil Tree and Pinball.

“No, wait,” I said. “Those are the books I worked on. Are you sure?”

“Definitely,” she said. “I remember the Times review of Pinball mentioned a misuse of the word limpid. I realized right away it was my mistake.”

Then it hit both of us: On weekends, all those months, she was double-checking me, and all the next week I was double-checking her, both of us thinking we were indispensable to Kosinski. We now realized that our man was willing to go to any lengths to make sure his written English would pass the toughest inspection.