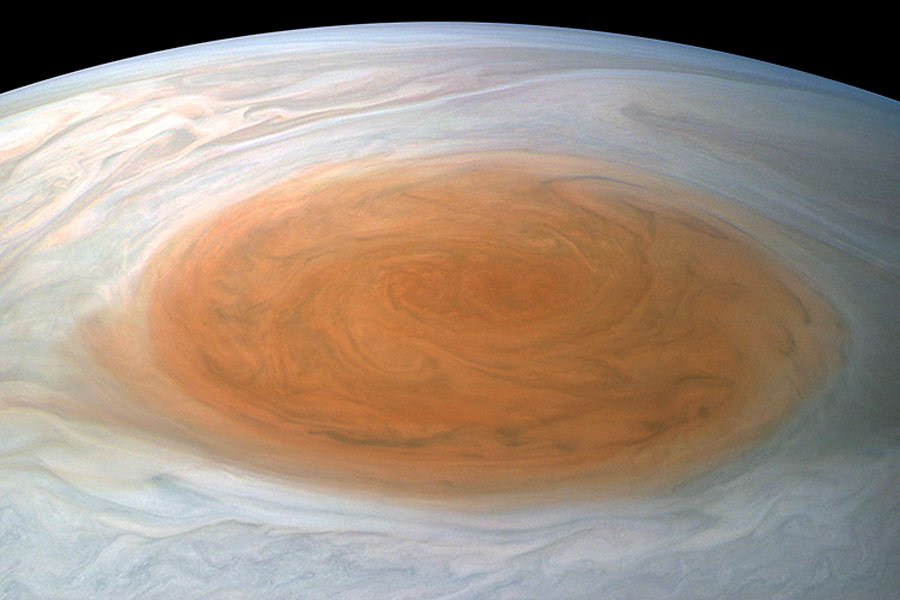

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Björn Jónsson

Observers have been tracking Jupiter’s Great Red Spot (GRS) for more than 150 years and perhaps as long as 358 years if Giovanni Cassini’s observations of a remarkably similar feature in 1665 are taken into account. Although the Spot’s discovery is sometimes credited to an observation made by English polymath Robert Hooke in May 1664, Marco Forlani makes an excellent case for Cassini’s primacy in a 1987 paper in the Journal of the British Astronomical Association. Either way, it’s a remarkably long time for a storm to stick around.

The apple of every Jupiter observer’s eye, the GRS is a persistent, high-pressure (anticyclonic) storm in the planet’s southern hemisphere caught between two opposing jet streams that work in tandem to keep it spinning much like a ball of Play-Doh rolled one direction between the palms of your hand. Data from NASA’s Galileo probe, which orbited the planet between 1995 and 2003, found that rising eddies of warm air from thunderstorms beneath the upper cloud deck provided the energy source to feed and maintain the monster spot. But a study published in 2021 based on Juno observations pointed to a source below the cloud base, revealing that the Great Red Spot’s roots reach no more than 500 kilometers (300 miles) deep.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Björn Jónsson

Like an earthly hurricane the storm’s center is relatively calm, but farther out winds blast between 430 and 680 kilometers per hour (270 to 420 mph). Like the Cookie Monster from the children’s TV show Sesame Street the GRS gobbles up smaller passing storms, which help to pump up its rotational energy while at the same time temporarily shrinking its diameter. Another key to its longevity is the fluid medium in which it resides. Unlike an earthly hurricane which quickly loses strength when passing over land, Jupiter is all atmosphere without the frictional barrier that land imposes.

NASA / ESA

Despite so many factors working to keep it “alive” the Spot may be in need of life support. It’s been shrinking for decades. In 2012 the rate of shrinkage abruptly accelerated, something many amateur observers have commented on since that time. Several years later, while still shrinking in diameter, it expanded in latitude becoming more circular. Now it’s narrowed again and continues to diminish in both axes. This observing season I’ve been struck by the Spot’s unusually small size. That, along with its pale pink color and turbulent environment, have made it less obvious than ever.

Christopher Go

Earlier this year the GRS spanned 14,750 kilometers (9,165 miles) in longitude (long axis) and 10,500 kilometers (6,525 miles) in latitude according to Amy Simon, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. She plans to remeasure its dimensions again later this year. In the meantime, avid planetary observer and astrophotographer Damian Peach has been photographing the Spot’s ever-diminishing girth.

Christopher Go

Using the WinJUPOS program and one of his recent high-resolution images, Peach measured the Great Red Spot’s diameter on November 6, 2023, at 12,500 kilometers or about 7,770 miles across. If confirmed it would make this season’s GRS not only smaller than the Earth (12,756 kilometers or 7,926 miles across) but the smallest size in observational history. A British Astronomical Association Jupiter section bulletin on October 30th described it as “the smallest it has ever been.” That’s a far cry from the late 1800s when the Spot ballooned to 41,000 kilometers (25,500 miles) — big enough to swallow three Earths with room to spare. Now it can barely contain one!

Thomas G. Elger (left), Damian Peach

As mentioned earlier, size is just one factor affecting the Spot’s visibility. The local environment can make a big difference. There’s not only a lot of turbulence in the clouds immediately following the GRS, but the Red Spot Hollow (RSH), a pale, pod-like region surrounding the GRS, is fairly dark and well-defined. Also, a short section of the South Temperate Belt (STB) lies close to the RSH’s border. All these features distract from the Spot’s pink fragility. Were they more subdued the GRS would appear that much more obvious.

In Simon and her team’s 2018 paper Historical and Contemporary Trends in the Size, Drift, and Color of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, she notes that the GRS continues to shrink at the rate of 0.194° per year in longitude (width) and 0.048° in latitude. Why its waistline continues to narrow is unclear. Simon found that the speed of its western drift in longitude has been increasing in recent years. Could that possibly shift the Spot to a location with less favorable winds or compromise its energy pipeline?

Whatever lies in its future — whether it will oscillate in size or continue to diminish and eventually resemble the planet’s other temporary red ovals — it’s a privilege to witness the metamorphosis of so large a structure in so short a time. Proof again what makes Jupiter a joy to observe. And there’s no better time than right now while the planet is still near its November 3rd opposition date.

To plan your GRS foray, be sure to use Sky & Telescope’s calculator showing when the feature transits the planet’s central meridian (you’ll also find that information in the current November issue of the magazine on page 50). I want to encourage you to email your Jupiter observations and photos to the Association of Lunar & Planetary Observers (ALPO) at [email protected] using their submission guidelines.

Find more information on Jupiter’s Great Red Spot and other phenomena in the November 2023 issue of Sky & Telescope magazine.