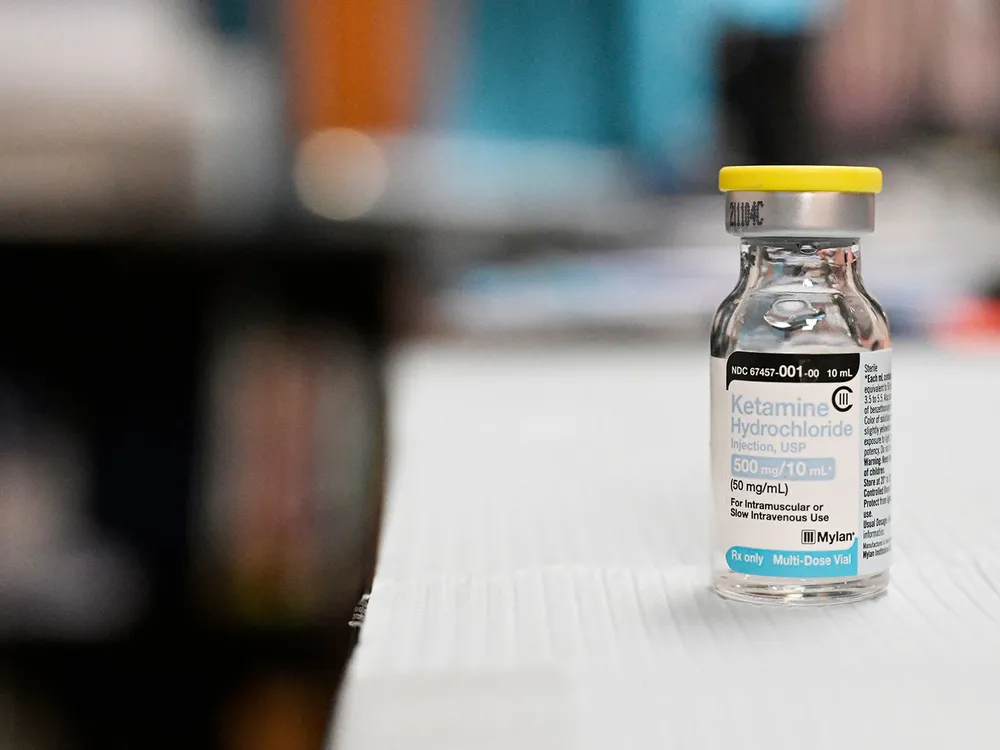

Ketamine and esketamine are the only psychedelics currently being used clinically with eating disorder patients.

RJ Sangosti / MediaNews Group / The Denver Post via Getty Images

Sarah Kelley was 14 years old when she first started to feel an intractable need to control her body and how it looked. She restricted her eating and ran for miles every day. “I would have times where it was pretty bad and impacted my ability to compete in cross country and soccer and to even function,” she says.

Only after her freshman year of college did Kelley first receive treatment for anorexia. She spent seven months in an inpatient program. Over the next decade, there were times when she could keep everything in check and days that were a struggle. In 2019, she had a more serious relapse: She found herself waking up around 4 a.m. so she could squeeze in two-hour-long runs before work, eating next to nothing, and then lacing up her sneakers again when she got home. “It became obsessive,” Kelley says. Her heart started to feel the strain, and she developed a murmur.

That’s when her therapist told her about a study on ketamine-assisted psychotherapy for individuals with eating disorders. One of Kelley’s former doctors was leading the case study, which was looking at how patients with diagnosed eating disorders and co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders responded to four weeks of ketamine injections.

“I got to a point where I had done talk therapy, been to treatment. I didn’t know what else to do,” says the now-34-year-old about why she decided to participate. “I wanted to heal and get better, but I was so terrified.”

A brief history of psychedelics

Hallucinogens have been used for centuries, primarily as part of religious rituals, by communities around the globe, from Indigenous peoples of the Americas to the ancient Greeks. The potential for psychedelics to address mental health issues was first realized around the 1950s—the same decade when the word “psychedelic” was coined by psychiatrist Humphry Osmond. By the 1970s, the drugs were labeled controlled substances in the United States, and conducting research with them became next to impossible.

But as mental health concerns and opioid misuse have grown in recent years, scientists have taken a renewed interest in the drugs. In 2000, researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine became the first to receive regulatory approval to restart psychedelics research in the U.S., and they’ve since found that psilocybin can help longtime smokers quit, reduce cancer-related anxiety and ease major depression.

Psychedelic-assisted therapy for eating disorders is an even newer frontier—and one begging for solutions. Eating disorders have the second-highest mortality rate among all mental health disorders, and one in five anorexia deaths is a result of suicide, according to the National Eating Disorders Association.

“It’s a very dangerous illness,” says Anne Marie O’Melia, chief medical officer and chief clinical officer at the Eating Recovery Center, an international treatment provider headquartered in Denver. “The prevalence of eating disorders definitely has increased with the pandemic,” she adds. Growing isolation and time on social media combined with decreased doctor’s visits and access to guidance counselors and other positive social influences have likely spurred the rise.

Because eating disorders often occur simultaneously with other health issues like anxiety, trauma and depression, the conditions are particularly complicated to treat. “There are no FDA-approved medications for anorexia, and only one for bulimia and one for binge-eating,” says Reid Robison, a board-certified psychiatrist and chief clinical officer of Numinus, a mental health care provider that uses psychedelic therapies in clinics in the U.S. and Canada. “There’s a big unmet need.”

Enter psychedelic treatments

Psychedelics have been shown to improve cognitive flexibility, stimulate neurogenesis (or build new pathways in the brain) and break through the rigidity and control that are touchstones of eating disorders—potentially accelerating the healing process. A 2015 study in the Journal of Psychopharmacology noted that use of the substances significantly lowered recent psychological distress and suicidal thinking, planning and attempts. “The client enters this, what we call a non-ordinary state of consciousness, where they can see things from a new perspective, perhaps have some insights about the path forward, have an experience,” Robison says. “And then what follows we call a state of neuroplasticity, or more openness to therapy, more ability to shape one’s patterns.”

“I think that this has potential to be one of the biggest innovations in eating disorder treatment in many years,” he adds.

Ketamine is the most thoroughly studied psychedelic medicine, though research is still in its infancy. “There’s a large body of evidence to suggest it is helpful with people with treatment-refractory depression, people with suicidality,” O’Melia says. “During the actual active period of the influence of ketamine, the patients describe to us they get some distance away from their thoughts.” The drug allows them to separate themselves, albeit briefly, from their eating disorders, she explains, and perhaps recognize that they have an identity beyond the rigid, controlled voices of their illnesses.

Other drugs are also showing promising results, at least in research settings: Psilocybin is being studied for the treatment of anorexia, and MDMA is being looked at for both anorexia and binge-eating.

But ketamine and esketamine—a modified version of the drug that has been approved for medical use as a nasal spray—are the only psychedelics currently being used clinically with eating disorder patients.

Patients like Kelley

Though she’d benefited from various treatments over the years, Kelley says her eating disorder was so severe that she couldn’t fully embrace them. Research is showing that psychedelic-assisted therapy may be most beneficial to individuals whose eating disorders have been resistant to traditional and intensive treatments. As another patient, who asked to remain anonymous, put it: “What intrigued me most was this idea that the ketamine would not cure me but would open up pathways so that I could heal myself. … That’s kind of what I was looking for—a way to think differently, to do things differently.”

As part of Robison’s study, Kelley received three courses of ketamine injections, with psychotherapy integration sessions taking place the day after each treatment.

Before entering the therapy room, Kelley and her therapist would set an intention—a word or mantra to guide the experience. Kelley chose “surrender” for her first session; it served as a word she could come back to throughout the session to remind herself to, as she puts it, “allow it to be whatever it needed to be.” The drug was administered in two intervals as Kelley relaxed into a recliner. About ten minutes later, she began to notice changes. “You just kind of feel funny—dissociative in a way, leaving your body or floaty,” she explains. “For me that was very terrifying. At first, I was pretty panicky.”

Her eating disorder developed out of a need to control her body. Now the ketamine was forcing her to relinquish that dominance. The foreign sensation scared Kelley. The clinician sitting with her encouraged Kelley to breathe. She surrendered to the feeling and began to see brown and black shapes; she interpreted them as her fear and panic and, as she watched them rise, recognized that she could move beyond them. “Even though I was in it, it didn’t last forever, and there was relief,” she says.

Subsequent sessions were even more impactful. In one, she saw a ball of light, moved toward it and recognized it as her younger self. “It was probably one of the most powerful experiences of my life and my healing journey,” Kelley says. For the first time in years, she felt she could reconnect with her body, rather than be at war with it.

Both Kelley and the anonymous patient found that the ketamine made them more willing to try new recovery behaviors or ones they’d resisted in the past, like following their meal plans or skipping a run. “I don’t think the ketamine was the cure,” says the 29-year-old who asked to withhold her name. “I think it just boosted my ability to interact with all the types of treatment that I was getting.”

That included talk therapy, where much of the actual work happened as patients processed their experiences post-ketamine treatment. That’s key, Robison says: “Psychedelics work best for mental health conditions when paired with therapy.” The integration sessions help individuals learn how to apply the insights they gained into their day-to-day lives.

Ketamine is not appropriate for all eating disorder patients, however. Because some psychedelic medicines can increase blood pressure and heart rates, for instance, patients are carefully evaluated for cardiac risks or a history of high blood pressure. Similarly, those with a history of psychosis would be at higher risk of entering a psychotic episode with the addition of psychedelics.

Besides feeling a little nauseous and woozy post-ketamine treatment, Kelley didn’t experience any side effects. No significant issues beyond nausea, low appetite, dizziness and hypertension have been recorded by researchers, either, though data is limited regarding long-term use. “We have not had any adverse outcomes,” says O’Melia when asked if there are any downsides. “But sometimes it doesn’t work.”

The future

The use of psychedelic-assisted therapies will likely continue to grow. In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration bestowed breakthrough status—essentially, speeding up the drug development and review process—on psilocybin therapy for major depressive disorder and treatment-resistant depression. In 2019, Spravato (an esketamine nasal spray) was approved for the treatment of treatment-resistant depression and, later, suicidality. And in June, the federal agency published a draft guidance to help researchers studying the potential for psychedelics such as psilocybin, LSD and MDMA to help treat substance use disorder, PTSD and other psychiatric disorders.

Robison, who works in Utah, has seen an uptick in clinics offering psychedelic treatments over the past couple of years but says they can still be hard to access for many patients, since ketamine is the only psychedelic-type medicine that can legally be used, and regulatory approvals for others can take years, even when fast-tracked.

And quite a few questions remain to be answered. Clinicians and researchers are still trying to home in on the right dosages, how many courses of ketamine therapy are needed and how long the benefits can last. Robison also emphasizes that psychedelics are not intended to be an indefinite treatment.

Kelley, for instance, has needed subsequent booster sessions. She returned to inpatient treatment in 2021, but she credits ketamine with sustaining the trajectory of her recovery. She’s used the psychedelic medically a handful of times since 2020 and still attends weekly therapy sessions and dietary meetings. “It’s not easy, and I don’t know how long it’ll take to get ‘recovered’ or fully there,” she says, “but this gave me an opportunity to have more hope and maybe see the light, I guess.”

A former teacher, Kelley is now in graduate school studying to become a clinical mental health counselor.

Recommended Videos