Hundreds of books, including a classic by Leo Tolstoy and a storybook by beloved children’s author Maurice Sendak, have been pulled from Florida school libraries this fall as administrators continue to scrutinize collections for works they fear violate new state laws.

Seminole County Public Schools has removed more than 80 books, including the National Book Award winner “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian,” this school year, and restricted access to 50 others by requiring parental permission or making them available only to high school students, according to Katherine Crnkovich, a district spokeswoman.

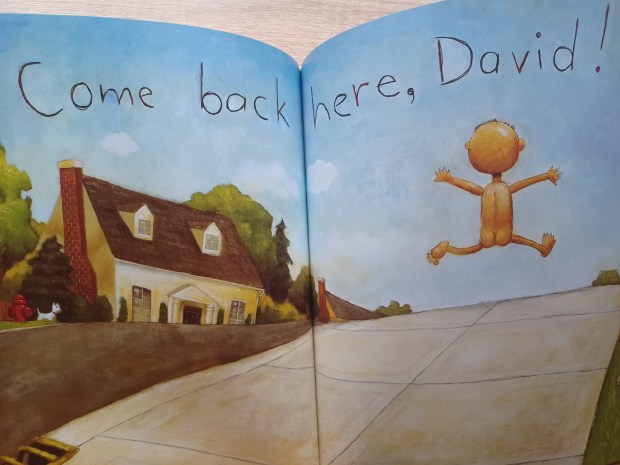

In Hernando County north of Tampa, six picture books were removed recently from school libraries, including Sendak’s “In the Night Kitchen” and David Shannon’s “No, David!” They all have illustrations that show kids’ naked bottoms, or, in one case, a goblin’s bare derriere.

A district spokesperson said in an email the storybooks violate a Florida law that bans books with “sexual conduct” from public school libraries. But Karen Jordan did not respond to follow-up questions asking how the funny illustrations of buttocks, or in the case of Sendak’s book, the small, cartoonish drawing of a little boy’s penis, amounted to “sexual conduct.”

In Collier County in southwest Florida, more than 300 novels have been taken from shelves, packed up and put in storage. They include works by Ernest Hemingway, Stephen King, Toni Morrison, Flannery O’Connor, Ayn Rand, Leo Tolstoy and Alice Walker.

The novels “Moll Flanders” (published in 1772), “Their Eyes Were Watching God” (published in 1937), “Slaughter-House Five” (published in 1969) and “The Kite Runner” (published in 2003) all met the same fate as did Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina” (published in 1878).

“They’re losing access to books — classic books, award-winning books and books written specifically for young adults,” said Amy Perwien, a Naples mother who said she was shocked to learn about Collier’s book removals and has urged her district to reconsider.

“We’re not protecting our students by denying them access to good literature, ” Perwien said. “The sheer number of books removed is really embarrassing for a district that prides itself on having excellent schools.”

Perwien, who has a son in a Collier high school, said her school district and others have overreacted to a new Florida law (HB 1069) that puts heightened scrutiny on library books, particularly those that “depict or describe sexual conduct.”

The Republican-dominated Legislature approved the bill in the spring, and Gov. Ron DeSantis signed it into law in May.

The law, an expansion of the 2022 law critics dubbed “don’t say gay,” aims to protect children from inappropriate material and pornography and also to prevent instruction in sexual orientation and gender identity in elementary and middle schools.

Neither of the law’s sponsors, Rep. Stan McClain, R-Ocala, or Sen. Clay Yarborough, R-Jacksonville, responded to emails or phone messages seeking comment on whether they intended the legislation to be so broadly interpreted that children’s picture books and classics often taught in high school English classes, such as Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World,” are removed from schools.

Conservative groups, particularly Moms for Liberty, have fueled book challenges across Florida, as members have shared lists of novels they want removed and sometimes read passages aloud at meetings. Their hope, as HB 1069 requires, is that if the school board stopped them from reading a book with sexual content, that book would be pulled immediately.

The group’s Seminole chapter celebrated the recent book bans on its Facebook page. “We’re at 97 books removed!!!” it posted earlier this month.

The count did not mesh with the district’s, but its enthusiasm for getting rid of books it considers obscene or too full of foul language was evident. “We have more books to challenge and we continue working on cleaning up the libraries,” another post read.

Critics and free speech groups like PEN America have decried the book removals. They say that some books are wrongly being labeled as pornographic, that descriptions of sexual conduct should not make library books automatically inappropriate for high school students and that too many of the banned books are about LGBTQ characters or racial or ethnic minorities.

They also note that most districts allow parents to restrict the books their own children can take out, which in their view makes the state’s actions heavy-handed and unnecessary.

Collier’s superintendent, Leslie Ricciardelli, said at her county’s school board meeting Tuesday that she knew Collier schools had taken a public “hit” for taking so many books from library shelves.

The actor and comedian Steve Martin on Instagram, for example, poked fun at the district for banning his book “Shopgirl,” published in 2002. “So proud to have my book Shopgirl banned in Collier County, Florida! Now people who want to read it will have to buy a copy!”

Books by popular authors including Judy Blume, Mary Higgins Clark, John Grisham and Jodi Picoult got packed away by Collier schools, too.

The state’s new laws and its training for school media specialists released in January gave her staff little choice, Ricciardelli said.

The state training told schools to “err on the side of caution” when selecting books and to be mindful that providing books with sexual content that is considered “harmful to minors” is a third-degree felony.

“I can’t apologize for the fact that we’re following the law,” Ricciardelli said.

Another law (HB 1467) passed last year is fueling book removals, too.

It required the Florida Department of Education to publish the list of all books objected to and removed in any Florida school district. The department encouraged districts to consult it.

The list of more than 380 titles removed last school year was published in August, and now some districts, including those in Seminole, Flagler, Sarasota and Volusia counties, are using it to review their own collections.

Seminole, which reported 31 books removed in early October, said it is now 85% through its examination of the state list, so more books could be pulled as educators complete the review.

“This is top-down censorship,” said Stephana Ferrell, a founder of the Florida Freedom to Read Project, formed to fight school book bans.

Orange County Public Schools hasn’t removed large numbers of books from the list, but it recently pulled four, including “The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author, according to an email sent to Ferrell on Oct. 31 and shared with the Orlando Sentinel.

“Y’all just quietly removed one of the most celebrated Black female authors of our time under a law that labels her work ‘pornographic,’” Ferrell wrote back to district leaders. “That should feel very heavy.”

Ferrell, who has two children in Orange public schools, said the state list is now trumping the expertise of school media specialists — certified teachers with additional library training — and the desires of local residents.

“The messaging from the state is that the state doesn’t ban books,” she said. “But the state’s list is influencing decisions.”

DeSantis has criticized what he called a “book ban hoax,” but PEN America said school book bans are on the rise nationally and in the 2022-23 school year Florida led the nation and was responsible for 40% of them.

The state’s list is dominated by books pulled in Clay County south of Jacksonville, where one father — who leads the Florida chapter of No Left Turn in Education — has filed hundreds of book objections and told the state he has plans to object to about 3,600.

On Tuesday, Gene Trent, a Brevard County School Board member backed by Moms for Liberty in his election last year, proposed removing all the books on that state’s list from Brevard’s school libraries, shocking some of his colleagues on the dais, who voted down his suggestion 3-2.

“These books have already been looked at, and that’s where I stand,” Trent said.

But others said Brevard should not automatically adopt what was done in other districts.

Board member Jennifer Jenkins, who voted against Trent’s suggestion, noted that one of the books on the state list was the “Little Rock Nine” by Marshall Poe.

The graphic novel is meant for children ages 8 to 12, according to its publisher Simon & Shuster, and is about school integration in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957.

“OK, sure, that must be like super offensive,” she said.

The book made the state’s list because the school district in Wakulla County, south of Tallahassee, decided in May to remove it from its elementary schools.

“If you really care about keeping our children safe,” Jenkins said, “you would worry about many other things than books.”