Israel has borrowed billions of dollars in recent weeks through privately negotiated deals to help fund its war against Hamas but is having to pay unusually high borrowing costs to get the deals over the line.

Since Hamas’s attack on October 7, Israel has raised more than $6bn from international debt investors. This has included $5.1bn across three new bond issues and six top-ups of existing dollar and euro-denominated bonds, and more than $1bn of fundraising through a US entity.

Investors said recent bonds had been issued in so-called private placements, a process through which the securities are not offered to the public market but instead sold to select investors.

The final pricing of the deals was not disclosed. However, bankers said they had priced in line with what they would expect from a public deal. Of two dollar bonds issued in November, Israel is paying coupons of 6.25 per cent and 6.5 per cent on bonds maturing in four and eight years’ time.

That is much higher than benchmark US Treasury yields, which ranged between 4.5 and 4.7 per cent when the bonds were issued. The deals were arranged by Goldman Sachs and Bank of America respectively.

In contrast, Israel issued a 2033 dollar bond in January with a coupon of 4.5 per cent, a much smaller spread — or gap — above Treasury yields, which were 3.6 per cent at the time.

Israel’s bond issuances to help fund the war are viewed as controversial in some parts of the debt market. While some investors, for instance in the US, have been keen to lend to the country following the October 7 attacks, others view the fundraising as anathema, given the humanitarian cost of Israel’s invasion of Gaza.

Investors and analysts noted that the bumper issuance was done through private placements rather than via open syndications and roadshows, which are usually carried out when new bonds are launched.

The reason for this, they said, could be to raise funds for the war effort quickly or without attracting unwanted attention, and could be a sign of how nervous some investors had grown about buying Israel’s debt.

“The reality is that, for a lot of investors, Israel at the moment carries too much ESG [environmental, social and governance] risk, especially for some emerging market investors where Israel is off benchmark,” said Thys Louw, emerging market debt portfolio manager at fund manager Ninety One.

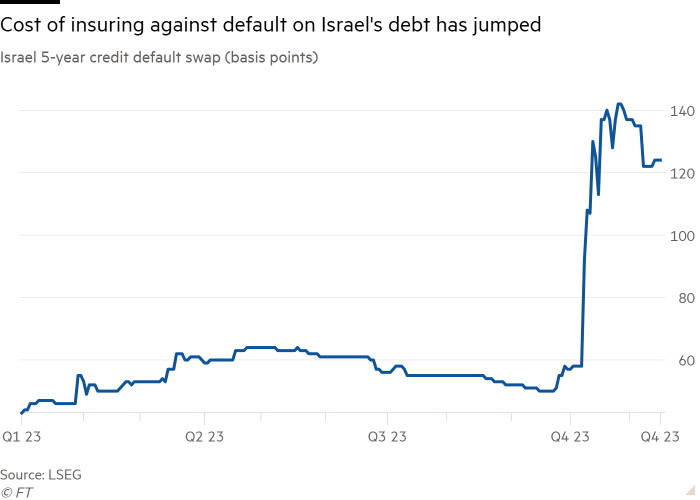

Caution about Israel’s debt is reflected in the surge in the cost of insuring against default on its bonds. The spread on five-year credit default swaps has widened from under 60 basis points in early October to about 125 basis points on Friday.

That compares with a spread of about 55 basis points for five-year CDS in Saudi Arabia, which has a lower credit rating from S&P.

“The market is still pricing a very high premium on Israel’s international debt, given that the war is ongoing,” said a strategist at one of the world’s biggest investment banks who asked not to be named given the sensitive nature of the topic. “In particular, the market is worried about how the war is going to impact Israel’s growth and public debt levels, and subsequent sovereign ratings.”

Israel’s finance ministry did not respond to a request for comment.

Israel has rarely struggled to find buyers for its debt in the past, owing to its strong public finances and interest from investors specialising both in emerging and developed markets.

But its economic outlook is deteriorating. JPMorgan said this week it expected Israel to run a budget deficit of 4.5 per cent next year, up from a previous forecast of 2.9 per cent. That could bring the government’s debt-to-gross domestic product ratio to about 63 per cent by the end of next year compared with 57.4 per cent before the war, the bank said.

The Bank of Israel has already downgraded its growth forecasts for the economy this year from 3 per cent to 2.3 per cent, and the cost of the war remains highly uncertain.

It is not the first time that Israel has privately placed bonds, as it did over the Covid-19 pandemic, to raise money urgently.

Investors note that Israel’s debt, which has a double A minus credit rating from S&P, is trading at a chunky discount to countries with similar credit ratings such as South Korea, which has a dollar bond maturing in five years with a current yield of 4.8 per cent.

“Israel’s bonds look extremely cheap,” said Paul McNamara, lead manager on emerging market debt strategies at GAM.

Brazil, which has a triple B minus credit rating from S&P, six rungs lower than Israel, issued a seven-year dollar paper this week in its first-ever foreign currency sustainable bond with a yield of 6.5 per cent.

Israel has also turned to individuals and municipalities to raise debt. Israel Bonds, which is registered in the US but affiliated to Israel’s finance ministry, has sold more than $1bn of bonds since October 7, almost doubling the amount it had raised for the year.

Dani Naveh, chief executive of Israel Bonds, told the Financial Times that most of the investment had come from the US and Europe, roughly evenly split between private investors and institutions, mainly represented by local governments.

Israel Bonds at present offer a 5-year term with a rate of 5.44 per cent and a 10-year term with a rate of 5.6 per cent. More than 15 US states have invested in Israel Bonds since the war broke out including Florida, New York, Texas, Alabama, Arizona and Ohio.

“We have never faced such huge support, in terms of the numbers or the scope of investments, by so many people,” said Naveh. “It allows the ministry of finance in Israel to raise billions of dollars of additional debt to fulfil all its special missions following the war.”