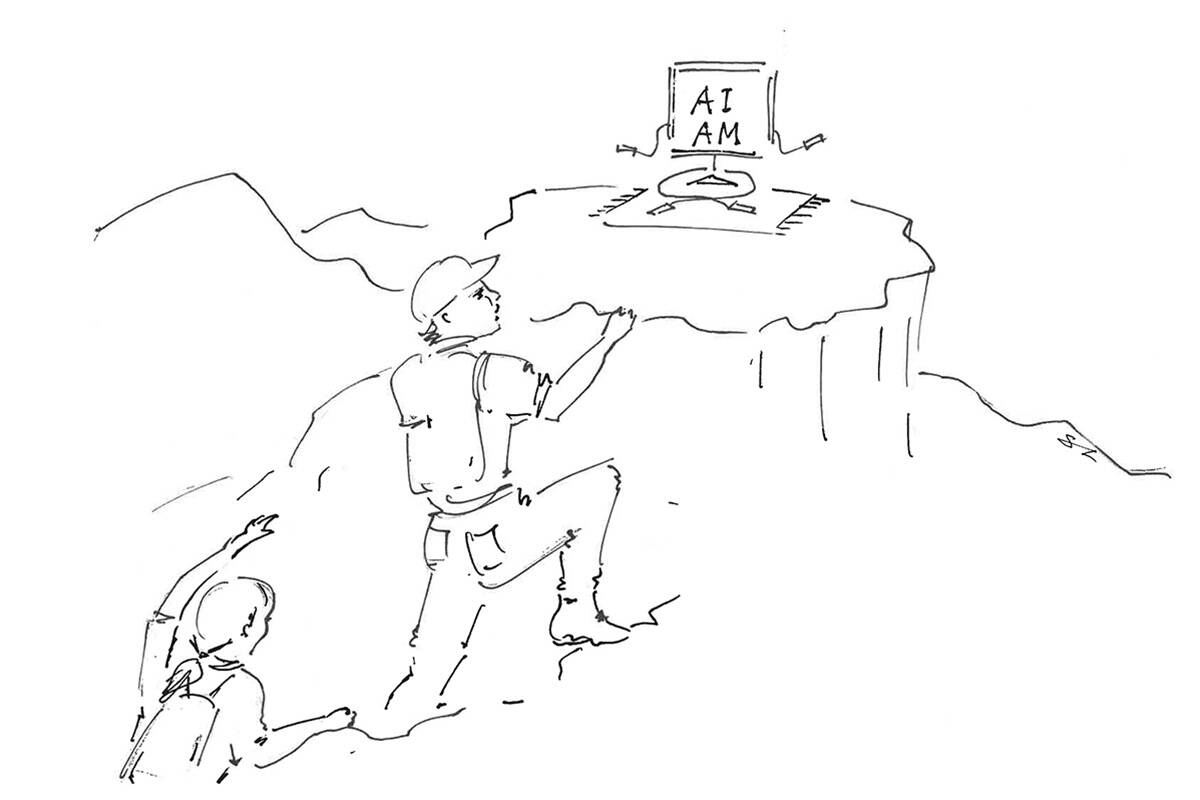

When Chat GPT-4, the artificial intelligence language-learning model, entered the American consciousness last spring, the internet quickly went on Armageddon watch. To believe the doomsayers, we were witnessing nothing less than a baby Skynet — the evil computer network from the Terminator films — take its first breath.

You know the story. The machines humans make become more powerful, are entrusted with more responsibility and then reach a moment of sentience where they look around, self-aware, and decide human beings are:

A) Idiots. B) Evil. C) Expendable.

… And, more or less, nuke the lot of us.

So what are we really dealing with here? The developer, Open AI, says that Chat GPT-4 — the latest in a series of language-learning models (LLMs) the organization has developed since 2018 —“can generate, edit, and iterate with users on creative and technical writing tasks, such as composing songs, writing screenplays, or learning a user’s writing style.” The LLM can handle 25,000 words of text, “allowing for use cases like long form content creation, extended conversations, and document search and analysis.”

Already, Chat GPT-4 can score a 163 on the LSAT, good enough to probably get into Top 20 law schools such as Georgetown, Vanderbilt and the University of Southern California.

In practice, this AI can help you write a report or paper, draft an email and summarize articles or other research. It can sort of do your work for you. It can also analyze and create images.

Of course, there’s a leap from the language-learning model of Chat GPT-4 to real, creative human intelligence. The dream (or nightmare) of Artificial General Intelligence, or AGI, in which machines can, as Open AI puts it, “outperform humans at most economically valuable work” is still on the horizon.

But the horizon may get here sooner than we wish. Last year, a Google engineer claimed that company’s AI chatbot, LaMDa, was already sentient. (The company denied this; the engineer was later fired.) Earlier this year, an organization called the Future of Life Institute released a much-reported-upon open letter signed by such prominent figures as Elon Musk, Andrew Yang and Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak. The letter, which as of mid-August had 33,000 signatures, called for a six-month moratorium on training AI systems more powerful than GPT-4. “Should we let machines flood our information channels with propaganda and untruth?” the letter asked. “Should we automate away all the jobs, including the fulfilling ones? Should we develop nonhuman minds that might eventually outnumber, outsmart, obsolete and replace us? Should we risk loss of control of our civilization?”

In an op-ed for Time magazine, Eliezer Yudkowsky, at the Berkeley, California-based Machine Intelligence Research Institute, argued the six-month moratorium was not bold enough. Only a complete shutdown will do. “Many researchers steeped in these issues, including myself, expect that the most likely result of building a superhumanly smart AI, under anything remotely like the current circumstances, is that literally everyone on Earth will die.”

We seem unlikely to consider these warnings. There’s too much at stake. Too much money to be made. Too many nations vying for power — economic, political, military.

Maybe it won’t end as Yudkowsky predicts. I’d draw your attention to another trope in science fiction: the inverse relationship between human behavior and machine behavior. As machines act more human, the humans around them act more like machines. This is part of the central thrust of 2001: A Space Odyssey, where clever, personable HAL interacts with a pair of monotonous, blank astronauts onboard a spaceship headed to Jupiter, while the rest of the crew exists in cryo-sleep like frozen meat. It’s only when the computer suffers a nervous breakdown and threatens the mission that the astronauts rouse themselves to creative action — and thus to human dignity.

Here, the machines don’t aspire to be more than human, some coldly calculating thing beyond empathy or love. They just want to be us. Best-case scenario? You wind up with Data on Star Trek: The Next Generation. He’s pretty cool; he actually reminds humans what’s special about being human.

Then again, HAL does go crazy and kills most of the crew.

According to a survey of 1,000 college students from Best Colleges, 43 percent have used ChatGPT or a similar AI application — and of those, half have used AI tools to complete schoolwork. Yet 57 percent “do not intend to use or continue using AI to complete their homework.”

I teach in the journalism program at UNLV. Along with the rest of the university, we are discussing how to handle AI in our classrooms. After the Terminator scenario, one of the next things people worry about is students simply phoning in their work. I joke with colleagues that we may soon see a world where artificial intelligence writes student papers — and artificial intelligence grades student papers.

But. Unexpectedly, my colleagues tell me that their students are reticent about using AI. As for its potential to corrupt, the students I’ve known over the years are mostly hardworking and conscientious. They want to learn, they want to improve, and they take pride in doing the work well. Is there a place for AI to aid them in these goals?

I asked a knowledge management program I use, Notion, which is running GPT-3, to tell me whether AI should be used to help students complete assignments.

Here’s what it told me:

“AI can help students to work more efficiently and effectively. It can provide personalized feedback and suggestions for improvement, and can also help to identify areas where students may be struggling. Additionally, AI can help to level the playing field for students who may not have access to traditional resources or who may have learning disabilities that make it difficult to complete assignments on their own.

“On the other hand … some worry that it may lead to a reduction in critical thinking skills or an over-reliance on technology. There may also be concerns about the accuracy and fairness of AI grading systems, particularly when it comes to subjective assignments such as essays.

“While it can certainly be a useful tool, it is not a replacement for human teachers or the critical thinking skills that are essential for success in any field.”

A perfectly reasonable, anodyne answer. If nothing else, Chat GPT-4 could enjoy a long career in politics. Good teachers likely would spot the “down the middle” blandness of this response — especially one with perfect grammar — and question the source. And yet, we already turn to prototype AI software to aid us. What teacher would take any student seriously who didn’t check their work with their word processor’s spelling and grammar check, which does a lot of the tedious work of copy editing and proofreading for them? For that matter, what editor or manager in any setting would respect their employee for submitting work without these checks?

I send interview notes off to a service that transcribes them for me, by computer, sparing me the indignity of line by line, four-finger typing transcription. That’s me trying to be a robot, you see, and the computer saying, “Nah, bruh, I got this …”

In the end, wherever we’re headed, AI is about work. Whether we’re talking schoolwork or on-the-job work, AI is just the latest automation technology that challenges us to think about what work means to us. Do we dream of a future when work has been made obsolete, or one when it’s been made more fulfilling?

LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman co-wrote a book with Chat GPT4, Impromptu: Amplifying Our Humanity Through AI, in which he noted the following: “Much of what we do as modern people — at work and beyond — is to process information and generate action. GPT-4 will massively speed your ability to do these things, and with greater breadth and scope. Within a few years, this copilot will fall somewhere between useful and essential to most professionals and many other sorts of workers.”

Processing information sounds sexy, but really that translates to the tedious, encroaching actions of the Digital Knowledge Economy that we all know so well: manipulating spreadsheets, sharing Google Docs, emails and PowerPoints, computer files, navigating tech support and a billion passwords.

The promise of AI is that it can save us from a world full of useless jobs and tasks, what the late anthropologist David Graeber referred to as bullshit jobs: “It’s as if someone were out there making up pointless jobs just for the sake of keeping us all working.”

It’s not so much whether you have a bullshit job or not … it’s that all of our jobs have some element of BS built in. Paperwork and procedures. It’s unavoidable, the normal, hungry maw of bureaucracy.

Can Chat GPT-4 — or -5, -6, etc. — take this off our plates, so that we might arrive on some sun-washed shore where work becomes more creative, more rewarding, less alienating? A world where AI isn’t used to fake a paper no one wants to write but to aid a student in deep, rigorous thinking? A world where work feels a little less like work and a little more like an enterprise that we have a real stake in, one that, moment by moment, day by day, is novel, challenging, valuable and draws out our best?

If we devise work that makes us feel like human beings, maybe there’s a way forward. If we devise work that makes us feel like machines, better machines are on the way. ◆