If you live in a long but narrow part of the world, you have an opportunity next month to contribute to a global project exploring one of the most famous and enigmatic stars. That’s because on December 12, on a path running almost half the way around the planet, the asteroid 319 Leona will pass in front of Betelgeuse, briefly blocking its light. That could be a fun thing to witness, something that will be possible without a telescope, but the details on how it happens could prove very scientifically revealing.

Betelgeuse is no ordinary star. As well as being the 10th brightest in our sky on average, it has the second largest angular diameter if you don’t count the Sun. As a very evolved star, it’s probably our best chance to get a front-row seat at a supernova, although debate continues as to whether that’s decades or almost 100,000 years away.

Uncertainty like that makes any information we can learn about Betelgeuse uniquely valuable. Nevertheless, when we can’t see it seems like an odd time to get the best information. It’s not as though anyone tries to study Betelgeuse during the day or on cloudy nights.

Nevertheless, many astronomers consider the timing excellent. Known as an occultation, the passage will mean that an observer in the right place will see about 94 percent of Betelgeuse’s light blocked, briefly reducing it to the status of a very ordinary star.

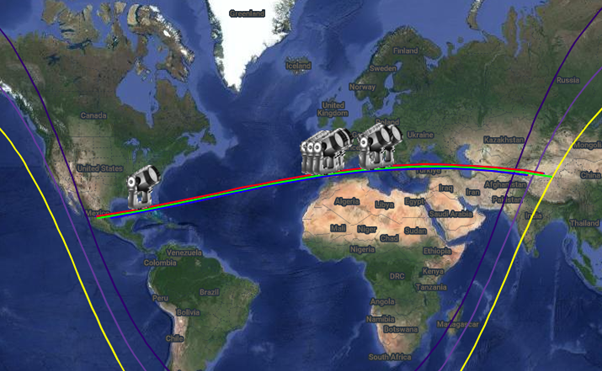

The current estimate of the occultation path (subject to slight revisions in red and green, with night areas inside the purple and yellow lines.

Image Credit: Occultwatcher.net. Last update SteveP

The reason this could be useful is that Betelgeuse is so unevenly bright across its surface. This isn’t a consequence of starspots, but its enormous convection cells, which also contribute to its overall variable brightness. However, it can be hard to map the distribution of these cells, because glare from the brighter parts interferes.

By comparing the way Betelgeuse dims from different locations along its path we may be able to map the cells’ distribution better than we have ever been able to do before. However, most of the path from which the occultation will be visible is over the Atlantic Ocean or the Mediterranean, and the odds are some of the land will be clouded over. That makes it crucial that observations are taken from as many places as possible, and professional astronomers would like amateurs’ help.

Even a simple DSLR camera with no telescope can provide useful data if correctly located. However, at the recent European Symposium for Occultation Projects, astrophotographer Bernd Gährken stressed it is essential that we know the exact timing and location of any observations. There are apps for Android and iPhone to help anyone who may be able to participate.

The event is of such significance that dozens of astronomers studied an occultation by 319 Leona on September 13 this year of a nameless star that requires a small telescope to see.

“In the overwhelming majority of the stellar occultations the diameters of the stars are tiny compared to the angular size of the solar system body that passes in front of them so the occultations are not gradual, but in this case, the huge angular diameter of Betelgeuse will give rise to a different phenomenon of ‘partial eclipse’ and ‘total eclipse’ (provided that Leona’s angular diameter is large enough compared with that of Betelgeuse.)” The authors point out.

Observing the September event helped refine Leona’s orbit and shape. improving predictions of where the December event will be visible.

Prior to the realization of where its path was taken, 319 Leona was not considered a particularly interesting asteroid. It’s 70 kilometers (40 miles) across – bigger than most we know, but hardly a giant – and orbits towards the outer part of the main asteroid belt. Leona is dark and reddish in color and is considered a P-type asteroid that rotates slowly, taking around 18 days to turn around.

That means that in the 17 minutes the occultation will be visible somewhere, Leona’s rotation won’t be much of a factor.

Curiously, preparations are hindered by the fact that we know Betelgeuse’s position in the sky less precisely than most stars. This counter-intuitive fact is a result of the Gaia space telescope being too dazzled by the brightest stars to place them. Other methods are less accurate than Gaia. Astronomers are struggling to resolve conflicting estimates of Betelgeuse’s exact location prior to the event, as it will affect exactly where they need to be to see the occultation happen.

The study of Leona’s September occultation has been accepted for Astronomy and Astrophysics Letters. A preprint is available on ArXiv.org