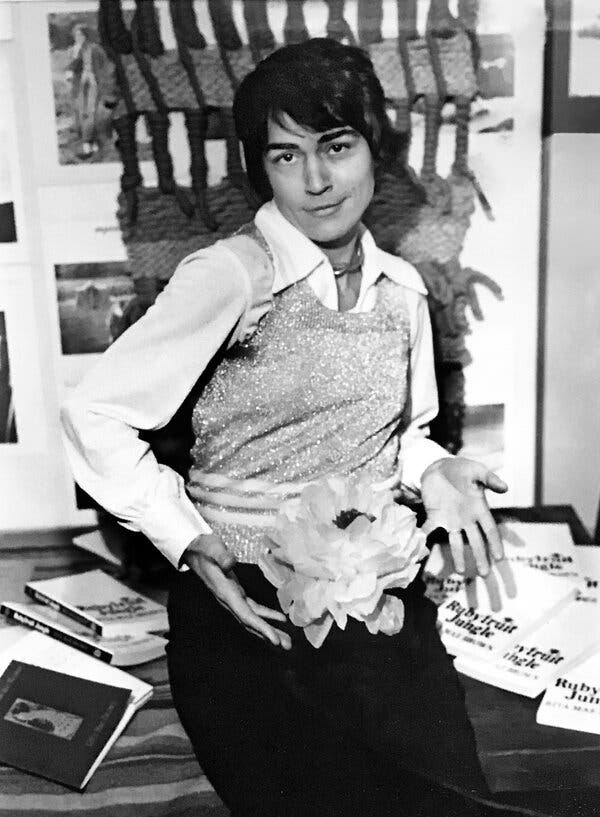

Molly Bolt may not be as renowned as Holden Caulfield, but to those who know her name, she is as much (if not more) of a literary hero. The precocious and fearless protagonist of Rita Mae Brown’s 1973 novel “Rubyfruit Jungle” has served as a model of possibility for generations of young women, lesbians and outsiders of all kinds.

Published by a small feminist press 50 years ago, the book became a crossover best seller when Bantam Books reissued it four years later, despite (and because of) its blatant sexual politics and embrace of queerness. With its erotic title and suggestive cover, the book became a secret for some readers to indulge privately, an experience which has shifted in the half-century it has been in print. Both of its time and ahead of it, “Rubyfruit Jungle” has inspired countless lives, works of art and Sapphic-themed spaces. Its author, meanwhile, has gone on to write scores more books, many of them popular mysteries.

Here, 12 writers and musicians, not to mention the owner of a bar named after the novel, reflect on the significance of Brown’s book and its uncompromising heroine.

Melissa Febos

Writer, “Body Work,” “Girlhood”

Oh, Molly Bolt. Was she my first crush? Maybe just the first one toward whom I was evenly split between wanting and wanting to be — a category that only grew over time, and included heartthrobs of all genders. I read “Rubyfruit” over and over, starting around 11 or 12, still a couple of years out from my first kiss with a girl. I, too, felt misfit for the place I was from. I, too, wanted to hitch to New York where the other artists were, where the other queers lived. Would I have gotten there as soon without Molly? Would I have been so willing to indulge the fetishes of strangers for a living if I hadn’t read about her indelible episode with the grapefruit guy? Probably not. Either way, her story felt like destiny. Molly was my Huck, my Holden, my Pip, my doorway to seeing hardship as adventure, my entreaty to blast forth into a future in which my desires could be realized.

Paula Vogel

Playwright, “How I Learned To Drive,” “Indecent”

I was struggling through my last year at Catholic University. I was as inspired by the phenomenon of the courageous Rita Mae Brown as by the book itself.As I passed the cowls, albs and habits, “Rubyfruit” gave me a secret reason to smile.

k.d. lang

Singer

From the opening scene …

And escorted by patsy cline.

I had found my planet.

Elizabeth McCracken

Novelist, “The Hero of this Book”

I was 15, and it was 1981, and I had recently acquired a $3-an-hour job shelving fiction at the public library. I got to the Bs pretty quickly and remember the sensation of reading “Rubyfruit Jungle” on the job. When my boss came near, I filed the book in my armpit. Then I fell back into the world and voice of Molly Bolt. My parents wouldn’t have minded — my mother might have read the book herself — but it mattered that I had found it myself and read it on the taxpayer’s dime. I had never read anything so serious and so hilarious. I still haven’t.

Myriam Gurba

Writer, “Creep: Accusations and Confessions,” “Mean”

I was dating a self-identified butch dyke, the kind who wore leather chaps, smoked cigars and rode a motorcycle. She had decided that I was her soul mate, that we were going to live together forever, and because we were star-crossed lovers, she needed to move all her possessions into the room I was renting in Berkeley, California ASAP. We borrowed a van, and my casa became our casa. I found “Rubyfruit Jungle” in a box of books that I helped her to unpack. “That’s one of my favorite books,” said my girlfriend. I’d already begun paging through it. “Let me know when you get to the part where the main character gets paid to beat up a guy with fruit.” That was my incentive to speed read. I loved the novel’s adventurousness. I also loved that it offered a template for how to be a lesbian in ways that weren’t depressing or dour.

Meshell Ndegeocello

Singer/songwriter

I had a short-lived job at the Oscar Wilde Bookshop, after giving birth in my twenties and failed attempts to conform to my mother’s hopes and dreams. I was brand-new to New York, new to myself. I felt a kinship to the location and the experiences of childhood in the book, especially the crushing burden of morality and shame viewed through the lens of Christianity. Some of the ideas are problematic and dated, like my own work I realize at times, but I am so blessed to be in one of the greatest cities in the world, free to love and to educate myself.

Jonathan D. Katz

Art historian, University of Pennsylvania

Amid the tortured coming out novels, the earnest LGBT political allegories and the semi-erotic, semi-closeted bildungsroman of my youth, “Rubyfruit Jungle” was much more than a breath of fresh air — it was an eminently queer tornado of a book. Ribald, joyous, and bawdy, the protagonist Molly didn’t wrestle with her sexuality, never apologized, and gleefully rejected anything that didn’t please her. Her story, for all the struggles it contained, was about something we hadn’t yet even named: queer joy. No wonder it shepherded so many coming out; it made queerness heroic — and I, like so many others, in the face of my Y chromosomes, wanted to be just like Molly.

Jill Sobule

Composer, lyricist, star, “F*ck7thGrade”

One day, my mom found the book under my bed, and called my dad up to tell him she was worried that their daughter was gay. My dad, wanting to be the cooler divorced parent, called me right back and said, “Honey, keep your things away from your mom.” He asked me to loan him the book when I was done. (He said he liked it.)

Kristen Arnett

Novelist, “With Teeth,” “Mostly Dead Things”

As a closeted teenager growing up in a conservative Southern Baptist Floridian family, I didn’t yet have a name for the thing I saw looking back at me in the mirror. My copy was beat up, pages pulpy-soft, stolen from a shelf in my English classroom. Curled up on my bedroom floor, I found a new God. Here I was!

Jenny Fran Davis

Novelist, “Dykette”

I got a library copy in college, maybe 2016, probably subconsciously needing to know that it was possible for gay writers to be both sexy and funny. Let’s just say there’s nothing repressed about “Rubyfruit Jungle,” the most delightfully perverted book I’ve read. Welcome to the second wave! The drama! The capital-M Metaphors! But honestly, the book is so sad, too — it’s about profound loneliness, and the impossibility of reality and fantasy ever really touching. I think it helped me be more brave about exploring the moral degeneracy and mundane wickedness in my own characters — what they want, and not what they should want.

Anne Hull

Writer, “Through the Groves”

I was 22 in the early ’80s when I read my first lesbian book, Radclyffe Hall’s “The Well of Loneliness,” about a Victorian-age “invert” who wore men’s britches and mourned her depraved state on the road to suicide. What a bag of downers, and not exactly encouraging. That was the beauty of “Rubyfruit Jungle” — it provided another way forward, one that involved sex with the captain of the cheerleading team. The market was broader than I’d imagined! Molly Bolt had no shortage of action; she was a heartbreaker, a total stud, and could care less what people thought of her. Meanwhile, I read “Rubyfruit” at the beach with a towel concealing the cover, envious of Molly Bolt’s courage.

Rich Juzwiak

Sex columnist, Slate

Coming to “Rubyfruit Jungle” as an adult (as I did recently), it’s a bit of a shock to feel humbled by a character who is self-actualized in adolescence. Molly is free of the internal struggles that typically dog queer characters and people both. “I can’t like anybody if I don’t like myself. Period,” she says at one point, using words that would be echoed decades later by RuPaul at the end of every episode of “Drag Race.” If Molly was ahead of her time it’s hardly surprising. All blueprints are, by design.

Emily Bielagus

Co-owner, The Ruby Fruit, Los Angeles

I came out when I was 25 years old. I felt like I had a lot of catching up to do. I immediately read every Lesbian Novel I could get my hands on. I also did a deep dive back into all the movies that seemed gay when I watched them as a child, just to confirm that they are, in fact, gay. (You cannot tell me Rosie O’Donnell and Madonna aren’t lovers in “A League of Their Own”). When it came time to name our wine bar, Mara and I wanted to evoke lesbian culture. Since we opened, I’ve noticed many friends, lovers, bar regulars and people within the larger lesbian community rediscovering “Rubyfruit Jungle,” or reading it for the first time. It’s as if we’re all reaching back into the pages of this novel to find clues about ourselves and our collective history.