C.S. Lewis’ lesson to his friends and fans—and to us—is that the cultivation of the imagination might require more than reading and writing, but it requires no less.

Readers likely know C.S. Lewis by the works of his imagination, first encountering him in the snowdrifts of the Narnian woods or on an omnibus bound for the vast green fields of The Great Divorce’s heavenly high country. Undoubtedly, Lewis is better known by the works of his imagination than by his advice on it, yet perhaps no other writer in the last century invested more in the imaginative capacities of others than did the author of works like The Magician’s Nephew, The Screwtape Letters, and Perelandra. Not only do we find in Lewis an imaginer, a creative who toiled a lifetime in the operations of the imagination, but also an imaginative adviser, a don effectively able to inspire imaginative exercise to others.

Readers likely know C.S. Lewis by the works of his imagination, first encountering him in the snowdrifts of the Narnian woods or on an omnibus bound for the vast green fields of The Great Divorce’s heavenly high country. Undoubtedly, Lewis is better known by the works of his imagination than by his advice on it, yet perhaps no other writer in the last century invested more in the imaginative capacities of others than did the author of works like The Magician’s Nephew, The Screwtape Letters, and Perelandra. Not only do we find in Lewis an imaginer, a creative who toiled a lifetime in the operations of the imagination, but also an imaginative adviser, a don effectively able to inspire imaginative exercise to others.

Now, the way to begin a conservation about Lewis and the imagination isn’t through an extraordinary wardrobe, but through rather ordinary books. Lewis’ imagination was born from reading. We can hardly find a work or letter by the writer without a reference to something he had read or was reading. The influence books had on Lewis began indelibly and early. In his spiritual autobiography, Surprised by Joy, Lewis offers an important bibliophilic picture that formed his early life —

I am a product of long corridors, empty sunlit rooms, upstairs indoor silences, attics explored in solitude, distant noises of gurgling cisterns and pipes, and the noise of wind under the tiles. Also, of endless books. My father bought all the books he read and never got rid of any of them. There were books in the study, books in the drawing room, books in the cloakroom, books (two deep) in the great bookcase on the landing, books in a bedroom, books piled as high as my shoulder in the cistern attic, books of all kinds reflecting every transient stage of my parents’ interest, books readable and unreadable, books suitable for a child and books most emphatically not. Nothing was forbidden me. In the seemingly endless rainy afternoons I took volume after volume from the shelves. I had always the same certainty of finding a book that was new to me as a man who walks into a field has of finding a new blade of grass.

Lewis spent his formative years roaming about a literary labyrinth. And the imagination by which so many readers would come to know Lewis remained well supplied by the thousands of images offered him in endless books. We would do well to see something prescriptive in Lewis’ description. Rather than merely recounting a literary-saturated childhood into which a writer might idyllically come of age, Lewis casts a vision for a dynamic imagination of which his life would serve as monument.

Long after Lewis had become famous as a creator of enduring imaginative worlds, decades removed from his boyhood bibliotheca, he received a letter from a seventh-grade school girl named Thomasine, who was given the assignment to write to her favorite author. She chose Lewis. Thomasine was to ask Lewis’s advice on becoming a writer. And in response, Lewis begins with, “It is very hard to give any general advice on writing,” but then goes on to share eight guidelines.

The second point of advice, right after “turn off the radio,” and the first active step in the imaginative process of writing, Lewis offered Thomasine was, “Read all the good books you can, and avoid nearly all magazines.” This, for Lewis, was the real business of the imagination. Reading stockpiled the imagination, carrying image after image from the page to the mind. The reader’s task was to be faithful in receiving what each book offered. As he wrote Australian poet Michael Thwaites, “Your first job is simply the reception of all this work with your imagination & emotions.”

Enduringly receptive, Lewis’ imagination remained the product of a voracious reading life. But the scholar, apologist, and fantasy writer didn’t just read widely; he read well. Because the imagination was formed by an act of reception, it conceived from what it received. What the imagination takes in, it gives out. As Lewis saw it, bad books make for poor imaginative fodder. Lewis lived by this principle. Both his published works and his personal correspondence testify that the long bookish corridors of Lewis’ mind stayed well-shelved with those works that bolstered his ability to make myth, convey meaning, and create beauty. And to those ends, it’s safe to say, he certainly avoided his share of popular magazines.

Lewis’ discriminate imaginative diet is evidenced by, “Who is Elizabeth Taylor?” That was his response when, in discussing the differences between “prettiness” and “beauty,” Lewis biographer and editor Walter Hooper suggested, “Miss Taylor was a great beauty.” Hooper further suggested to Lewis, “If you read the newspapers, you would know who she is,” to which Lewis responded, “Ah-h-h-h! But that is how I keep myself ‘unspotted from the world.” Lewis insisted that if Hooper had to read the newspapers he “have a frequent ‘mouthwash’ with The Lord of the Rings or some other great book.”

Lewis, once described as the “best-read man of his generation” and “one who read everything and remembered everything he read,” operated from the overflow of his intake of great books. And if what we know about his imagination’s cultivation teaches us anything, it’s that his reading life was a long inspirative inhale, and writing, creative exhale. Now, Lewis was a tireless writer—lest we think that he was given to mere bookishness—whose reading proved more than an end in itself. Reading is the start of a process of imagination reification, what Lewis describes as an incentive that becomes an itch: “The ‘incentive’ for my books has always been the usual one—an idea and then an itch or lust to write.”

Lewis elsewhere describes this journey from incentive to itch in terms of image and form. As Lewis puts it, the writer comes upon a mental image that grows within the imagination beyond the boundaries of mere contemplation. Something must be done. Something must be written. Lewis describes it as something clawing to escape:

In the author’s mind there bubbles up every now and then the material for a story. For me it invariably begins with mental pictures. This ferment leads to nothing unless it is accompanied with the longing for a form: verse or prose, short story, novel, play or what not. When these two things click you have the Author’s impulse complete. It is now a thing inside him pawing to get out. He longs to see this bubbling stuff pouring into that form as the housewife longs to see the new jam pouring into the clean jam jar. This nags him all day long and gets in the way of his work and his sleep and his meals. It’s like being in love.

To Lewis, the imagination moved along the lines of creative compulsion. Between image, engendered by reading, and form, expressed through writing, exists within the writer a dynamic generative energy. We don’t have to read long in Lewis to find him characterizing writing as an inner coercion, a force moving the writer’s will. To poet Martyn Skinner, Lewis said about writing’s addictive appeal: “The right mood for a new poem doesn’t come so often now as it used to. Ink is a deadly drug. One wants to write. I cannot shake off the addiction.” To his closest lifelong friend, Arthur Greeves, who was at the time Lewis wrote at work on a continuation of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, called “Alice for short,” Lewis charged, “I cannot urge you too strongly to go on and write something, anything, but at any rate WRITE.”

In another particularly poignant appeal to Greeves, Lewis further admonished, “I hope that you are either going on with ‘Alice’ or starting something else: you have plenty of imagination, and what you want is to practice, practice, practice.” In the same vein as the way Lewis built his fantastic imagination through feverishly reading all the books he could, he advised others to cultivate their imaginations by faithfully writing all they could. To Greeves, he continued, “It doesn’t matter what we write (at least this is my view) at our age, so long as we write continually as well as we can. I feel that every time I write a page either of prose or of verse, with real effort, even if it’s thrown into the fire next minute, I am so much further on.”

To Lewis, it wasn’t often the lack of mental images or banal thinking that caused imaginative atrophy. Rather, an underdeveloped imagination could simply result from a negligence of the practice of writing, of creative laziness. Hence, Lewis’s tendency to push for further craftwork in his letters: “You MUST go on with this exquisite tale: you have it in you, and only laziness—yes, Sir, laziness—can keep you from doing something good, really good.” It isn’t a refusal to think on the whimsical or a failure to ponder the fanciful that Lewis warns against. It’s a lack of creative enterprise. It’s an unwillingness to do the work required a creator that quenches the spirit that would make an imaginer.

So in advising on the operations of the imagination, Lewis gets to what he thought was the heart of the matter: unfaithfulness to the work of writing. In a letter written in the year before his death, Lewis encouraged a child named Jonathan, an avid fan of Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia, to take up writing his own stories: “Why don’t you try writing some Narnian tales? I began to write when I was about your age, and it was the greatest fun. Do try!” And to another child, named Sydney, Lewis exhorted, “I’m afraid I’ve said all I had to say about Narnia, and there will be no more of these stories. But why don’t you try to write one yourself? I was writing stories before I was your age, and if you try, I’m sure you would find it great fun. Do!”

For these two fans of Lewis’ fantasy, asking if they would ever read a new Narnian tale, Lewis’ replies likely came as surprise. Rather than delve deeper into his imagination, they ought to do the work of building theirs. After reading, writing would be their straightest path into the imaginative. If they were to go further up and further in the space of the imaginative, they must go about it positively nagged by image and form, taken up with book and pen. Indeed, Lewis’ lesson to them—and to us—is that the cultivation of the imagination might require more than reading and writing, but it requires no less.

This essay was first published here in August 2017.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

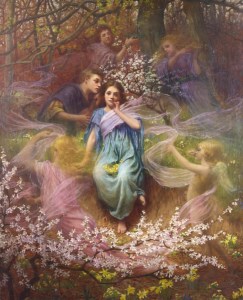

The featured image is “Phantasy” (1896) by William Savage Cooper and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.