When Chief Roger Hill speaks about the clean energy project going up along the border of the Tonawanda Indian Reservation, he turns quickly to the past. Hill’s Seneca ancestors once controlled a large territory across the rolling, wooded hills in what is now western New York, but most of their lands were taken through a series of treaties that shrank the reservation to its current size.

The territory’s borders have remained unchanged for a century-and-half, but Hill says that a new hydrogen fuel plant being erected about 2,000 feet beyond them is now threatening his nation’s way of life.

“This is all we have, so this is why we’re so adamant in protecting the last piece of land,” said Hill, who sits on the council of chiefs for the Tonawanda Seneca Nation. “We want that there for our children, our grandchildren, their children, our great-grandchildren.”

With backing from state and local government, a company called Plug Power is building a project that will use zero-emissions electricity to produce hydrogen, a clean-burning fuel that could replace oil and gas in heavy-duty trucks and equipment.

The plant would produce 74 tons of hydrogen per day and could help New York meet ambitious targets to phase-out fossil fuels. The Biden administration has also set a goal to produce millions of tons of clean hydrogen annually by the end of the decade as part of its plan to slash the nation’s climate pollution.

The Plug Power site is part of a larger planned industrial development that local and state officials have been pushing for more than a decade, promising to bring high-tech, clean energy jobs to the area. Gov. Kathy Hochul and Charles Schumer, the Senate majority leader and New York Democrat, have lent sustained and prominent support, steering tens of millions in state and local tax incentives and subsidies to the development. The effort has struggled, however, with only two tenants for the industrial site secured so far. Plug Power also reported recently that it is facing a financial shortfall.

The Tonawanda Seneca Nation has opposed the development from the start, arguing that it would degrade the bordering woodlands in which its citizens hunt, fish and forage for medicine and food. The hydrogen project and another planned development have already brought high-voltage power lines and promise to bring increased truck traffic to a rural area adjacent to the nation’s territory.

While the development has undergone environmental reviews by state and federal agencies, Hill said his people have not been adequately consulted and that their appeals to block or alter the development to lessen its impacts have been ignored by officials.

Over the last decade, many Native Americans have fought to highlight the disproportionate impacts they have faced from fossil fuel development, with new pipelines crisscrossing their territories and traditional lands from North Dakota to Louisiana, threatening the land and water with spills and pollution. In response, the Biden administration and New York officials have made addressing environmental justice a cornerstone of their plans to launch a new clean energy industrial revolution.

In her state of the state speech this year, Hochul said she was committed to hitting New York’s climate targets “in a way that prioritizes affordability, protects those who are already struggling to get by, and corrects the environmental injustices of the past.”

Tonawanda Seneca leaders and their allies say Hochul and other officials are breaking those promises.

“It’s not random in my mind that the state decides to put it right at the edge of one of these nations today,” said Neil Patterson Jr., assistant director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment at the State University of New York and a citizen of the nearby Tuscarora Nation. “If I were New York State, I would be utterly embarrassed. The state that somehow talks about diversity, equity and inclusion, and what they say is a just transition given climate change impacts, but continuing to wage the Indian War.”

The Big Woods

Tucked into the northeastern corner of the 7,500-acre territory is an expanse of forest and swamps that the Tonawanda Seneca call the Big Woods. Much of the area has never been cut, the nation’s leaders say, giving it old-growth characteristics rare in the Northeast.

“There’s a different feel there,” said Scott Logan, a Bear Clan sub-chief of the nation. Hunters get turned around, he said, lost in its majesty. “There’s enormous hardwoods, hundred years-plus, where there’s no branches for 40 feet. It’s created a canopy almost like a rainforest.”

Medicinal plants seem to grow faster in the Big Woods, the nation’s citizens say, and in greater abundance. Its soaring canopy protects a relatively open understory, ideal for hunting and gathering plants. The nation commissioned a survey of the woods by the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment, which found a “remarkably low” incidence of invasive plants and robust populations of forest floor herbs.

“It is, I like to say, one of the most biodiverse areas remaining in upstate New York,” said Patterson Jr., who led the study.

The nation’s citizens make tea from the Big Woods’ slippery elms. Bear root and wild lettuce provide medicines for pain and other ailments.

“You can smell the woods, you can smell the medicine,” said Vance Wyder, a nation citizen who has been hunting and foraging in the woods since his grandfather first taught him to make baskets, rattles and shoes from slippery elms and turtle shells when he was a child. “You can literally talk to the trees, and you can listen to what’s going on in there, and you can ask them for help,” he added. “And they give it to you.”

In an affidavit for a since-dismissed lawsuit, Wyder spoke about a species of frog that eats a particular flower in the Big Woods, causing the amphibian to extrude a medicinal substance. Another citizen, who makes traditional lacrosse sticks using deer hide harvested in the woods, testified that about 100 people hunt there regularly, with the animals they kill providing the bulk of the protein in many of their diets.

Plug Power’s hydrogen project is less than a third-of-a-mile away from the Big Woods across an open field, and the nation’s citizens fear the noise and activity will scare away wildlife and degrade the ecosystem. Accidents, they fear, could lead to explosions or fires, or pollute the waters that flow through the woods.

While work at the hydrogen plant has proceeded, with two large spherical tanks standing in the middle of a cleared lot, Plug Power has been struggling financially. In a securities filing this month, the company said that it had yet to achieve profitability in any quarter since it began in 1999, and had accumulated a $3.8 billion deficit.

“We have incurred losses and anticipate continuing to incur losses,” the filing said, “and there is a substantial doubt that we will have sufficient funds to fund our operations through the next 12 months.”

Plug Power did not respond to repeated requests for comment for this story, but Andy Marsh, its chief executive, has projected confidence in recent interviews that his company will pull through, noting its lack of debt. In an interview with Yahoo Finance, he said that if the company can’t raise additional funds, it could slow work on the projects it is developing, “which would reduce our capital needs.”

On the same day that it reported its financial troubles this month, however, Plug Power also said the New York plant would be commissioned next year.

The company has promised nearby residents that the hydrogen plant would have minimal impacts, saying that noise from operations will be below the area’s natural, background levels and that the only waste it will produce is a non-hazardous salty material resulting from filtering water.

Those assurances, and the company’s financial troubles, have done little to assuage the Tonawanda Senecas’ fears.

“A lot of people from American society don’t understand our connection, our intergenerational connection, and how deep it runs within us to the land and the Earth,” Logan said.

Logan described a thanksgiving speech, or Ganö:nyök, that the Seneca recite to recognize the natural world around them.

“We start at the Earth and we go all the way up to the sky, to the creator, and it covers everything from the water, the plants, food, medicine, trees, birds, animals, everything in the natural environment,” Logan said. “If any one of those things goes away, eventually we will perish.”

A Lack of Consultation

By the time Hill and other Tonawanda Seneca leaders first learned the details about Plug Power’s hydrogen project, on Jan. 26, 2021, planning was well underway. The company had already submitted an environmental assessment form for the project about a month earlier, according to a lawsuit the nation filed later that year. The Tonawanda Seneca immediately requested a meeting with the Genesee County Economic Development Center, the local agency that is behind the broader industrial development that includes Plug Power’s proposal.

The parties held a Zoom meeting on Feb. 5, but according to the lawsuit, county agency officials failed to mention that they had enacted a resolution the previous day declaring that the project’s environmental impacts had been adequately addressed. The Nation did not learn about this resolution until two weeks later, when it received a letter from the agency’s counsel.

How could the potential impacts be adequately addressed, Hill and other leaders wondered, when the nation hadn’t even been consulted?

Throughout more than a decade of planning for the industrial site, Tonawanda Seneca leaders say that local, state and federal agencies have repeatedly cut the nation out of the process. There was the draft general environmental impact statement for the site, in April 2011, which referred to the nation erroneously as the “Seneca Nation of Indians.” (The Tonawanda Seneca split from the Seneca Nation in the 19th century.) The statement had little to no mention of the potential impacts of development on the nation’s territory, the lawsuit said.

In 2018, when the county economic development agency proposed rerouting power lines closer to the Tonawanda territory, the nation objected and asked for a pause, according to the lawsuit. The rerouting proceeded anyway. A year-and-a-half later, the county agency determined that a change in plans for the site’s wastewater treatment and disposal would not have adverse impacts, again without consulting the nation, the lawsuit said.

More recently, the nation has accused the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which had issued a permit to the county agency to drill a wastewater line underneath a federal wildlife refuge, of failing to properly consult with the nation. In May, after the nation protested, the service said it would temporarily suspend the permit and perform a new environmental review incorporating the nation’s concerns. But two weeks later, it informed the nation that in fact it did not have the authority to suspend the permit. In August, the service issued a new review, which the nation argued still lacked the promised consultation.

On Sept. 29, the wildlife service did order the county to halt work on the pipeline, but not because of the Tonawanda Seneca’s concerns. Three weeks earlier, as contractors plumbed beneath the refuge, 100 gallons of drilling fluid erupted onto the surface, covering one-third of an acre. Several sinkholes appeared elsewhere along the route, in one spot pulling the shoulder away from a stretch of asphalt road.

A spokesperson for the service said in a statement that, “while we have been consulting with the Nation for more than a year, we believe we can do more,” adding that it would “enhance our consultation with the Nation” over the industrial park development.

The Tonawanda Seneca have argued that, by failing to initiate an adequate dialogue with the nation, the county agency, state Department of Environmental Conservation, or DEC, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have all violated state and federal laws that require such consultation.

A DEC spokesperson said that the department was “participating in ongoing government-to-government consultation with the Tonawanda Seneca Nation, per DEC policy.” He added, “DEC is committed to holding permittees accountable for violations of State Environmental Conservation Law and other permit requirements in place that are protective of public health and the environment.”

The county agency has come under fire from environmentalists and others in the area, too. Local environmental groups have questioned the site’s location, nestled between the reservation and several state and federal wildlife refuges. They have told state agencies that industrial development could erode habitat for threatened species of birds, including the short-eared owl and northern harrier, and have aligned themselves with the nation’s concerns.

Orleans County, to the north, recently filed a lawsuit against the Genesee County agency, accusing it of evading state law by creating a “sham” sewer works company to acquire easements for its wastewater line through Orleans County.

The Genesee County Economic Development Center declined to comment for this article, citing the pending lawsuit filed by Orleans County.

While the county has performed preparatory work at the industrial site, such as routing high-voltage power lines to the area, the only tenant it has secured other than Plug Power is a company called Edwards that makes industrial vacuums used in semiconductor manufacturing.

Alex Page, the nation’s legal counsel, said the Tonawanda Seneca’s position that state and county agencies had violated environmental laws remains unchanged, but that an appeal of the dismissed lawsuit faced long odds.

But Logan, the Tonawanda Seneca sub-chief, brought up the nation’s history with the federal government, dating back to 1794, when asked why the nation didn’t pursue the legal case further.

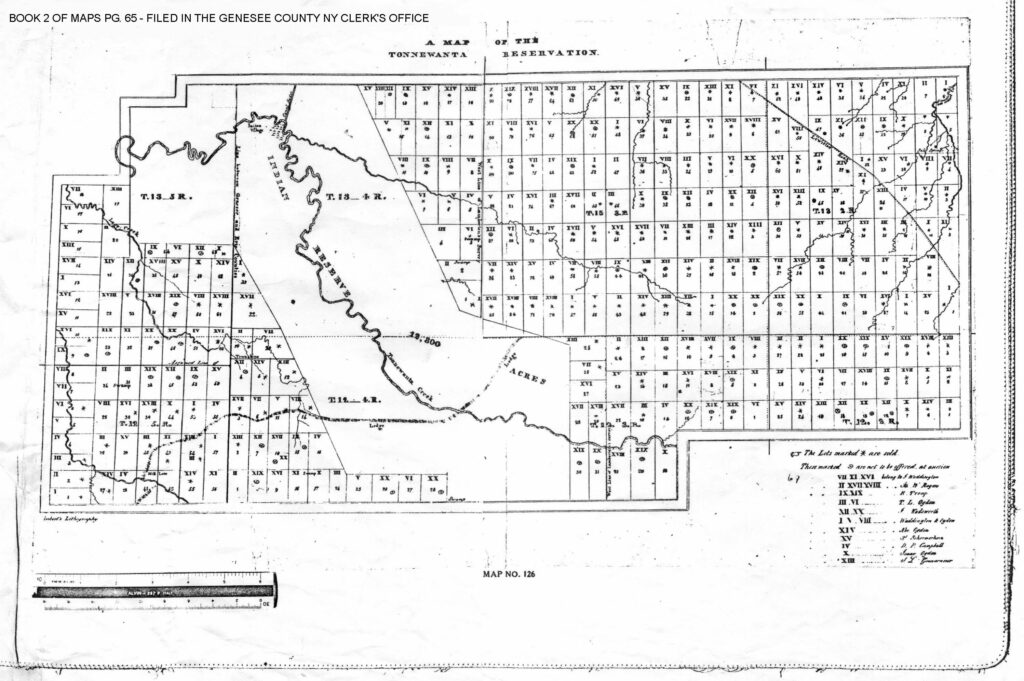

The Tonawanda Indian Reservation, one of 11 originally granted to the Seneca, once covered 70 square miles. But over the next several decades, a series of treaties shrank and eliminated some of the reservations, including Tonawanda, as the historian Laurence Hauptman recounts in The Tonawanda Senecas’ Heroic Battle Against Removal. A private company took control of the land instead.

Tonawanda leaders contested the treaties and eventually secured a favorable ruling from the Supreme Court, which led to the recognition of the Tonawanda Seneca as their own nation. But rather than simply granting the land back to the Tonawanda Seneca, the federal government gave them the “right” to buy back only a portion of their land, using funds that had been appropriated to remove the inhabitants from their New York reservation and relocate them to Kansas.

“That’s what winning looks like to us,” Logan said. “This is our history with the American government.”

Ancient Beliefs

Hydrogen has become one of the most hyped promises in a clean energy transition. The gas is highly flammable but releases no climate pollution when burned, meaning it could, theoretically, replace natural gas in industrial processes that require high heat, like steel manufacturing. It can also serve as a battery, effectively, in something called a fuel cell, potentially helping replace diesel or other fuels in trucks and ships, where conventional batteries might be impractical.

This hope has directed an enormous amount of public funding towards the fuel in recent years. The bipartisan infrastructure bill of 2021 allotted $8 billion to help build hydrogen “hubs” around the country (While New York was part of a regional application to receive some of that money, it was not among the winners announced in October). Last year’s Inflation Reduction Act created a new clean hydrogen tax credit that could be worth tens or hundreds of billions of dollars, depending on how successful companies are in producing the fuel.

But many scientists and environmentalists have warned that a new hydrogen economy could fail to deliver meaningful climate benefits without the proper guardrails, and could even hold back a shift away from fossil fuels. Plug Power says it will use emissions-free electricity from a state-run hydropower operation to pull hydrogen molecules out of water, with oxygen as the only byproduct. (Patterson Jr. pointed out that one of the hydropower project’s reservoirs flooded land that had been taken from the Tuscarora Nation in 1960).

But it is unclear whether the company can prove that those same electrons it is purchasing wouldn’t otherwise be used by another customer, a factory or farm, for example. Because the grid is interconnected, new demand for clean power can increase demand for fossil fuels unless it is matched with an equal, additional supply of renewable electricity.

This question of “additionality” is one of several that dog hydrogen production, even when it is powered with clean electricity.

The Treasury Department is currently writing the rules that will determine how stringent companies must be on questions including additionality in order to qualify for the federal tax credit. Plug Power is one of several companies that has lobbied for leniency.

Plug Power had already lined up about $270 million in potential state and local subsidies and incentives, including property tax abatements and a discounted electricity rate, according to a 2021 analysis by the Investigative Post, a nonprofit news organization. That worked out to about $4 million for each of the 68 jobs the project promised to create, though Plug Power has since announced an expansion at the site that would create an additional 19 jobs.

New York political leaders, including Hochul, the governor, and Schumer, the Senate majority leader, have long supported the Genesee County industrial development, arguing it would bring thousands of jobs to an economically-depressed part of the state and help with a transition to clean energy. Neither Hochul’s office nor Schumer’s responded to questions for this article.

“We all have this trauma-based paranoia of, ‘You just want my land. You don’t care about us. You just want something from us or want us gone,’” Logan said. “We haven’t been able to get rid of that in our own emotions, we haven’t been able to. So when something like this comes along, there are so many red flags that come up.”

Logan questioned the benefits that the hydrogen project will provide, saying it is part of a misguided attempt to address climate change with further industrial development. Their fight against the project is part of what the Tonawanda Seneca see as their duty to serve as stewards of the land, Logan said, and to preserve it for future generations, long past the life of Plug Power’s project.

“Our culture, our way of life, is old. It’s ancient beliefs and ancient ways of life and ways of thinking, and it doesn’t match today’s society, it doesn’t match technology today. But we want to preserve that,” Logan said. “We believe that’s what’s going to save us in the long run.”