Further South in Mexico, however, an effort is underway to make this knowledge-sharing model work. In 2022, two Wixárika communities in Mexico agreed to an ambitious project to document their rich knowledge of plants, traditional farming practices, and the language they use to describe them. This knowledge is at risk as people increasingly leave the area to pursue wage economy jobs and opt to speak Spanish instead, especially because the country’s education systems, medical systems, and legal services are conducted in Spanish. “Wixárika people, like many local and Indigenous groups, heavily manage wild plants by transplanting them, pruning them, encouraging them, protecting them,” said Alex McAlvay, an ethnobotanist of the New York Botanical Gardens. The words for those practices, he said, “are also quick to disappear as well as the knowledge they encode.”

McAlvay is part of a collaboration of linguists and botanists that is also helping to record the Wixárika names for places, which often reflect gods, animals, or plants associated with them. The word paixarita, for instance, describes the riverine, rocky home of a plant with grape-like acidic fruit, explained Wixárika linguist Gabriel Pacheco of the University of Guadalajara and linguist Stefanie Bierge of the New York Botanical Gardens. Though the plant is seldom found in these areas anymore, the place’s name documents its historical presence, providing insights into how the landscape has changed due to forces like climate change.

Not all of the Wixárika knowledge will be made available to researchers. A select, community-approved subset will be shared in the form of audio and video recordings through a database of endangered languages. Instead, the bulk of the project will focus on creating resources for the community: an online database, a botanical handbook, educational materials on botanical knowledge, audio and video recordings of Indigenous speakers, and herbaria collections of dried plants. For the Wixárika people involved in the project, the goal is to preserve and revitalize their knowledge and encourage younger generations to learn about traditional practices. “Even if we’re probably not using the knowledge on an everyday basis,” Bierge said, translating a statement spoken in Spanish by Pacheco, “this kind of work is vital to preserve the knowledge.”

In Australia, some documentation efforts are even further along. A few years ago, the Atlas of Living Australia, which catalogs the country’s species, launched a project to incorporate Aboriginal ecological knowledge alongside the Western scientific data it contains. One focus, for instance, has been documenting the ancestral knowledge of elders from Noongar communities of the southwestern corner of the country, much of which has been lost to government assimilation policies. For the Noongar clan Wudjari, “two that I work with are the last speakers of the traditional language,” said Denise Smith-Ali, a Noongar linguist at the Noongar Boodjar Language Center in Perth who participated in the documentation efforts.

Only the knowledge that elders wish to share beyond their families is shown on the Atlas—which oftentimes, they do. As a result, Smith-Ali said, “we now have an opportunity to teach [Western scientists] what we do know.”

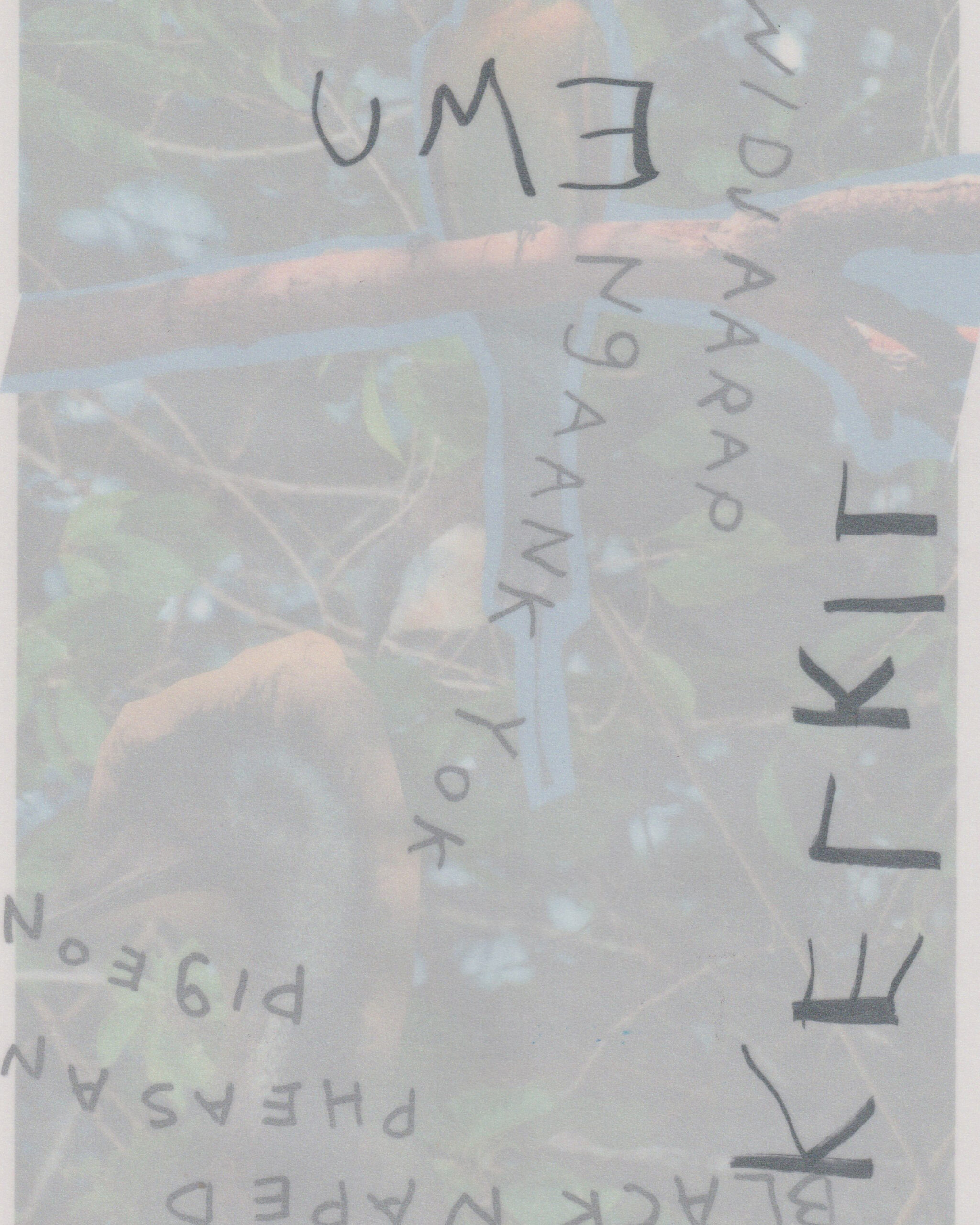

The Atlas’s page for “emu,” for instance, now includes roughly two dozen Indigenous names for the species and connects to more Aboriginal knowledge—such as a Noongar encyclopedia entry that details the uses of feathers for art and ceremonies, what its meat smells like, and that the protective males won’t leave the nest, even during a bushfire. Compared to Western science, Indigenous science considers species more holistically, how they link to the land and to people, said Nat Raisbeck-Brown, a spatial scientist at Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization who leads this project. For example, one subdialect of Noongar describes a eucalyptus species as “Widjaarap Ngaank Yok,” which includes the mountain where it grows, the shape of the nut and flower, and the term for “woman.”