It could take him days to write a sentence. From July to November 1853, he labored over a single scene. He suffered, as if from a physical ailment, from “scribbling whole pages” without producing any satisfactory lines. During the first 18 months of the most consequential love affair of his life, he wrote his paramour around 100 letters but condescended to see her in person only six times. He had the audacity to inform her outright in a tactlessly honest missive, “I worry more about a line of verse than about any man.”

He worried — and worried, and worried — about practically nothing else, even when he was on the verge of flunking out of law school, or when he was diagnosed with epilepsy, or when fights broke out in the streets of Paris in 1848. All the while, he was entombed in the provinces, anxiously recording the rate of his writing: “25 pages in six weeks,” one page in five days, 112 pages in 10 months.

This was, after all, the unit in which he measured the progress of his life, and he could be histrionic about his skirmishes with the page. Once, when he was struggling with a nascent novel, he exclaimed, “I’m like a toad squashed by a paving-stone … like a clot of snot under a policeman’s boot.” There was no metaphor too visceral, too vicious, for the violence of composition: “I suffer from stylistic abscesses,” he complained, “and sentences keep itching without coming to a head.” But for him there was no conceivable alternative. When a friend urged him to hurry up and publish something already — he was, by this time, into his 30s — he replied, “May I die like a dog rather than hurry by a single second a sentence that isn’t ripe!”

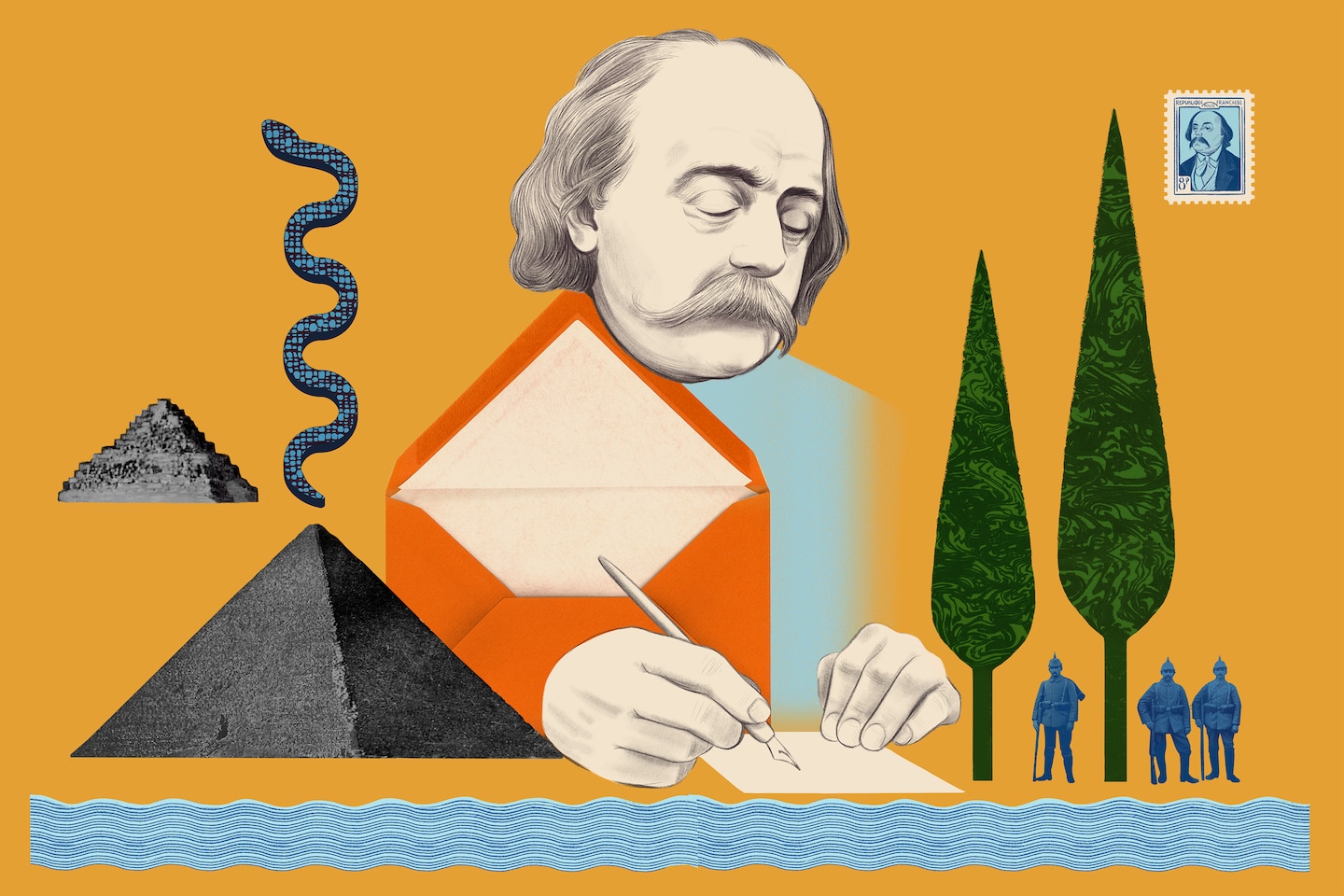

He was, of course, the French immortal Gustave Flaubert, and he was rewarded for his fanaticism with one pristinely perfect novel (“Madame Bovary”); one very good novel (“A Sentimental Education”); one first-rate novella (“A Simple Heart”); two fascinating but decidedly overwrought failures (the operatic novel “Salammbô” and the hysterical play-cum-phantasmagoria “The Temptation of Saint Anthony”); a handful of forgettable stories; a few works of predictably indulgent but occasionally effervescent juvenilia; a promising but unfinished final effort; and perhaps the loveliest, liveliest correspondence in the history of literature.

His letters, recently reissued and collected in a single volume for the first time, are every bit as hilarious and humane as his best fiction. Scholar, translator and devotee Francis Steegmuller (1906-1994) provides helpful and occasionally wry interjections and explanatory essayettes that are a delight in their own right. When Flaubert notes that he does not want to write like several of his contemporaries, Steegmuller clarifies with mordant relish in a footnote: “The present obscurity of these names speaks for itself.” Steegmuller’s sparkling commentary is substantive enough that “The Letters” doubles as a critical biography. And this is the only sort of biography it is possible to write of Flaubert: A biography of the man is really a biography of the style.

If Flaubert has one sin, it is sacrificing substance to form. The critic Walter Pater described him as a “martyr of literary style,” and there is no question that style was his foremost obsession. The word appears more than 70 times in the letters. “Style is achieved only by dint of atrocious labor,” he wrote in 1846. Five years later, he was still laboring, still atrociously: “I foresee difficulties of style, and they terrify me.” Six years after that, he reported, “The chimera of style … consumes me body and soul.” He once fantasized about writing “a book about nothing,” a book sustained by beauty alone. The author’s mother reproached her son for his empty formalism. “Your mania for sentences,” she scolded, “has dried up your heart.”

Flaubert’s letters demonstrate that he colluded in constructing the myth of his inhuman austerity. He is famous for the doctrine of “impersonality,” according to which the author must ruthlessly remove traces of himself from his work. “The greatest, the rare true masters, are microcosms of mankind: not concerned with themselves or their own passions, discarding their own personality, they are, instead, absorbed in that of others,” he wrote in 1846 to his lover, poor Louise Colet, designated by Steegmuller as a “very minor poet” and now remembered chiefly as the novelist’s correspondent. Shakespeare, Flaubert wrote of his most monumental idol, “is a terrifying colossus: one can scarcely believe he was a man.”

This philosophy of rigid detachment prevailed not only in Flaubert’s writing, but also in his life, or so he was fond of boasting. Though he allowed himself a bout of uncharacteristic patriotism during the Franco-Prussian War, he was for the most part proudly apolitical and defiantly indifferent to fads and fashions. He hated newspapers (a “paltry way of publishing one’s thoughts”), disdained reviewers (criticism “serves no purpose except to annoy authors and blunt the sensibility of the public”) and made much of his allergy to all things contemporary (he jokingly chose as his patron Saint Polycarp, who is purported to have wailed, “Oh God, oh God, in what a century hast Thou made me live!”). His ignorance of the news was almost a matter of faith: He regarded discussions of current events as “an indecency among intellectuals,” and he often cautioned his friends against the temptations of “the world.” Some of them were not amused by his quixotic naiveté. His good friend George Sand, a lesser novelist but a superior political theorist, excoriated his approach as a “hibernation in ice.” Flaubert was undeterred, and he continued to present himself as a demiurge, at once tyrannically sovereign and sublimely unconcerned.

Flaubert’s fiction alone is sufficient to belie this pretense. He is credited with inventing (or at least perfecting) an aloof brand of realism, but his more bombastic efforts make it difficult to see him as a champion of restraint. “Salammbô,” a historical effulgence set in Carthage, glitters with palaces “encrusted with gold, mother of pearl, and glass,” and in “The Temptation of Saint Anthony,” the titular hermit finds himself tempted by “black hashes, jellies the color of gold, ragouts in which mushrooms float like nenuphars upon ponds, dishes of whipt cream light as clouds.” Even when he begs God to strengthen his resolve for asceticism, he cannot resist extremity. “Accept my penance, O my God,” he cries. “Render it sharp, prolonged, excessive.” These are the books about nothing that Flaubert dreamed about writing. Their only event, their only real character, is the sickeningly sumptuous style itself.

But the letters provide an even better refutation of Flaubert’s self-conception. Beginning when he is only 9 and ending when he dies of a cerebral hemorrhage at age 58, they are rife with autobiographical disclosures of the sort he sought to expunge from his fiction — and better yet, they reveal the extent to which all of his prose is permeated with his personality. “If style is the man, greatness of style is greatness of person,” the art critic and philosopher Arthur Danto wrote. It is hard to think of a statement Flaubert would have rejected more strenuously, but all the hallmarks of his fiction — the lightly mocking tone, the exacting eye for detail, the delight in incongruous juxtapositions of high and low — are present in the letters from the very first line.

Born in 1821 in the small city of Rouen, Flaubert was strikingly precocious. From a remarkably young age, he had the same single-minded fixation. “Let us continue to devote ourselves to what is greater than peoples, crowns and kings: to the god of Art,” he wrote to a friend when he was 13. He would continue to voice versions of this sentiment, sometimes even more emphatically, for the rest of his life. At 17, he mused: “If I ever do take an active part in the world it will be as a thinker and de-moralizer. I will simply tell the truth: but that truth will be horrible, cruel, naked.” This prognosis proved prophetic.

Thankfully, a second prediction in the same letter turned out to be less prescient. “My life, in my dreams so beautiful, so poetic, so vast, so filled with love, will be like everyone else’s — monotonous, sensible, stupid,” he wrote. “I’ll attend Law School, be admitted to the bar, and end up as a respectable assistant district attorney in a small provincial town.” This is precisely what would have happened to one of his characters, but it is not what happened to him. Flaubert’s oppressively sensible father succeeded in corralling him into law school in Paris, but that was as far as the attempted bourgeoisification went. In the end, he was saved from the prospect of a legal career by some combination of a mental breakdown and the onset of his epilepsy, which his parents interpreted as a nervous ailment. He affirmed this convenient assessment, writing to a friend, “My nerves quiver like violin strings.”

He returned home in 1844, and two years later, his father died of complications from a surgical procedure; two months after that, his sister gave birth, contracted an infection and followed suit. Flaubert and his devastated mother went to the family’s country house in Croisset, a picturesque village on the outskirts of Rouen. There the author remained, save for two trips to the Middle East and many brief visits to Paris, for the rest of his life.

Yet his days were not uneventful. For one thing, there were the perennial entertainments of his voice, his point of view. And as he wrote indignantly to a friend who entreated him to move to Paris, “humanity exists everywhere,” even in the provinces. Indeed, there were innumerable dramas in idyllic Croisset. Some were personal: Flaubert weathered a turbulent affair with Colet, who demanded more devotion than he could ever muster, and cultivated passionate literary friendships with a number of other writers, with whom he fought and reconciled. Some were sexual. On Flaubert’s first trip to the Middle East, he visited many prostitutes and ended up fretting about his genital chancres.

Then there were the explosive dramas of publication: the obscenity trial to which “Madame Bovary” was subjected in 1857, the splenetic letters Flaubert exchanged with critics who savaged “Salammbô” in 1862 and the constant fights with editors who dared to offer suggestions (“I will not make a correction, not a cut; I will not suppress a comma,” he huffed). There were also the adventures (and consolations) of intellectual life — he read and reread Shakespeare, adjudged Balzac’s prose lacking but admired his books all the same, and struggled to master Greek. And above all, there was the constant crisis of writing itself.

None of these romantic, institutional or artistic entanglements prevented Flaubert from posing as a literary recluse. One of the great themes of his fiction is the tragicomedy of aggrandizing delusion, but his novels somehow did not equip him to recognize how mistaken he was about himself. He insisted in a letter to Colet that he had decided “to put on one side my soul, which I reserved for Art, and on the other my body.” In truth, he was not capable of separating art and physicality because he wrote with his body, with the whole rush of his blood. Literature was as arduous as war, as kinetic as sex, and the letters seep with secretions. When Flaubert is working well, “something deep and ultra-voluptuous gushes out of me, like an ejaculation of the soul” ; when “Salammbô” began to pick up momentum, Flaubert declared: “I’m beginning to have an erection.” “I’m sweating blood,” he told a friend when he was in the thick of a battle scene.

Flaubert’s formalism was not cold, but carnal. He acknowledged as much when he reflected that a book consists of its language to the same extent that a person consists of her entrails: “Just as you cannot remove from a physical body the qualities that constitute it — color, extension, solidity — without reducing it to a hollow abstraction, without destroying it, so you cannot remove the form from the Idea, because the Idea exists only by virtue of its form.” There is no spirit independent of its surface.

In other words, Flaubert’s style is so succulent that it constitutes its own substance. “I derive almost voluptuous sensations from the mere act of seeing,” he wrote in a letter in 1845, and his writing has the quiet quality of Dutch still lifes, which dignify prosaic things by practicing patient and painstaking observation. The shores of a river, glimpsed from the deck of a boat in “A Sentimental Education,” “slipped away like two wide ribbons being unspooled”; gunshots during a political uprising sound like “the tearing of a huge piece of silk”; Emma Bovary carries a “parasol, of dove-gray iridescent silk, with the sun shining through it,” which “cast moving glimmers of light over the white skin of her face.” This writing is not the least bit impersonal, the least bit objective. The lovingly selected details for which Flaubert is celebrated are not a pane but a patina.

Nor had the mania for sentences dried up Flaubert’s heart. On the contrary, style is “an absolute manner of seeing things,” as he wrote in a letter to Colet, and it is also a manner of cherishing them. The philosopher Simone Weil once enigmatically proposed that “attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity,” and reading Flaubert’s letters alongside his fiction, I think I understand what she meant.

In “Madame Bovary,” the jilted husband adores his wife’s most commonplace gestures. He gapes at “her hand touching the bands of her hair, the sight of her straw hat hanging from the hasp of a window”; he is entranced by her habit of “forming pellets of soft bread on her thumb.” He cuts a ridiculous figure, and yet there is something admirable about his obstinately careful appreciation. Flaubert is not unlike a lover who marvels over trivialities and thereby hallows them. He lavishes attention on neglected and forlorn minutiae. And what is a style so laboriously perceptive if not a form of love?

Becca Rothfeld is the nonfiction book critic for The Washington Post.

The Letters of Gustave Flaubert

Edited and translated from the French by Francis Steegmuller

NYRB. 716 pp. $24.95, paperback