Writers and Company54:20Looking back at A.S. Byatt, the celebrated English novelist and imaginative intellectual

Featured VideoIn honour of novelist and critic A.S. Byatt, who died on November 16, Writers & Company revisits her 2009 interview with Eleanor Wachtel, recorded live at the Blue Metropolis International Literary Festival in Montreal. Byatt was there to launch her novel, The Children’s Book, and to receive the festival’s $10,000 Grand Prix. *Please note this interview includes reference to suicide. It originally aired on May 24, 2009.

WARNING: This audio contains discussion of suicide.

This fall, as Writers & Company wraps up after a remarkable 33 year run, we’re revisiting episodes selected from the show’s archive. This conversation originally aired on May 24, 2009.

From the time-jumping mystery romance Possession to the decade-spanning story of intertwining families The Children’s Book, A.S. Byatt’s fiction has delighted, challenged and transported readers for decades.

The British author died on Nov. 16, 2023 at age 87 after a remarkable 60-year career as a novelist.

As a tribute to her and her contribution to literature, this week’s Writers & Company episode revisits her 2009 interview with Eleanor Wachtel at the Blue Metropolis International Festival in Montreal.

Byatt was born in 1936 to John and Marie Drabble. John was a King’s Counsel and judge and Marie was a teacher and homemaker. The oldest of four children, notably fiction writer Margaret Drabble, Byatt grew up in a Quaker household where bookish practices, such as quoting poetry on car rides, she told Wachtel, prevailed.

Fiction as escapism

A fervent reader from a young age, Byatt explored literary worlds, often with a torch under the covers after bedtime, searching for escape and excitement.

“The real world was intensely boring,” she said. “I don’t think anybody, even my children’s generation, has experienced boredom the way we did.”

“There is a sense I have now that everybody needs, as it were, an unreal world to complete the real world that they have to inhabit.”

There is a sense I have now that everybody needs, as it were, an unreal world to complete the real world that they have to inhabit.– A.S. Byatt

Byatt studied English at Cambridge University, then continued on to postgraduate studies at Bryn Mawr College and University of Oxford, determined to work after observing her mother’s dissatisfaction at being a homemaker.

Her mother told her that she had sacrificed her work to look after her family, Byatt said, and only seemed truly happy when she was teaching at a boy’s grammar school during the war — the one time when married women were allowed to take up those positions.

“It taught me that women must work. That if you wanted to work, you must work,” she said.

“If you’re aware of somebody having sacrificed their work for you, it makes you unhappy. And then everyone’s unhappy.”

In 1959, she married Ian Byatt and moved to Durham, which caused her to lose her academic grant, she told the Paris Review in 2001. However, she was secretly pleased because she could then focus on writing fiction, she said.

At the time, she had already written drafts of her first two novels, The Shadow of the Sun and The Game, published by Chatto & Windus in 1964 and 1967 respectively.

She had a son and a daughter before divorcing Ian Byatt in 1969. She then married Peter Duffy, with whom she had two daughters.

In 1972, her 11-year-old son Charles was hit by a car and died, which had a profound effect on her and her creativity. This was shortly after she had taken a teaching post at University College London to pay for his schooling, where she continued working for 11 years before leaving to write full time.

It wasn’t until 1978 when she published again, this time writing the first in a series of four novels, The Virgin in the Garden. The second in the sequence, Still Life, came out in 1985.

Intellectually ambitious literature

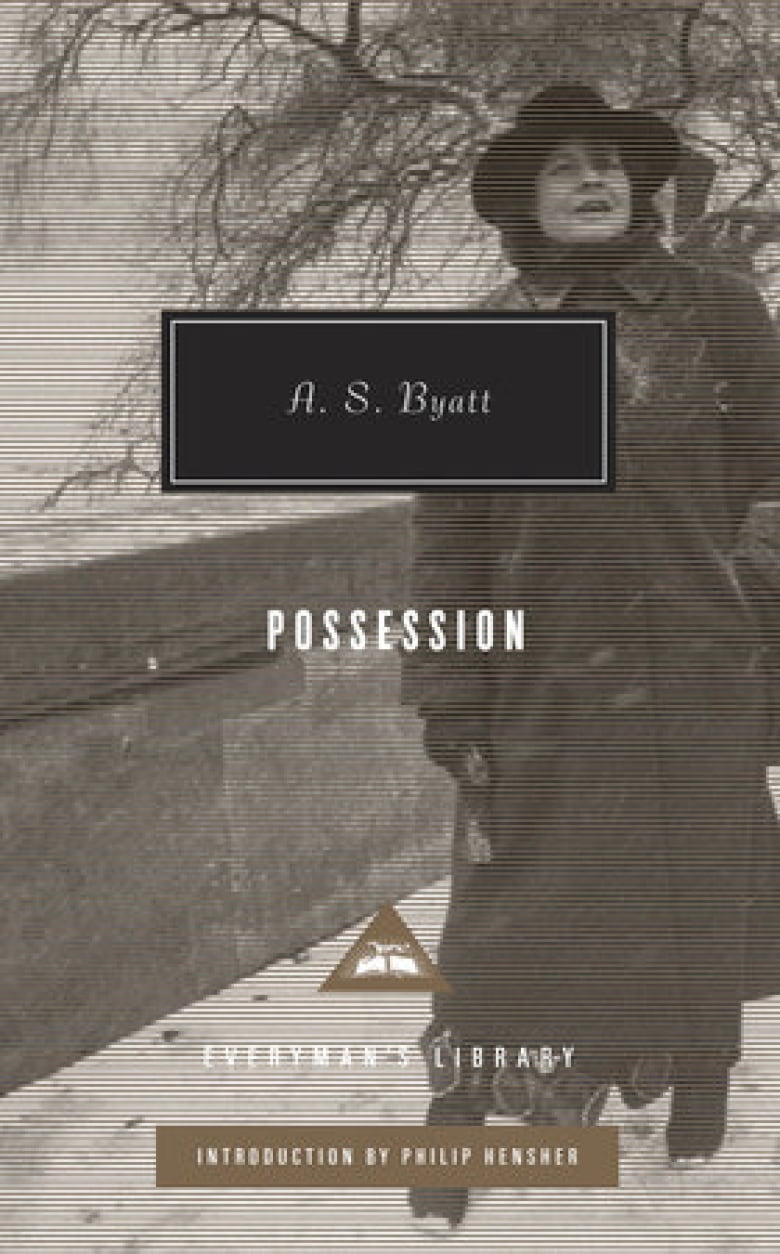

But what propelled Byatt into literary stardom was her 1990 novel, Possession: A Romance, which won the Booker Prize for Fiction and the Irish Times International Fiction Prize. Told through love letters, lines of original poetry and dense, detailed prose, Possession follows academics Roland Mitchell and Maud Bailey as they uncover a secret romance between Victorian poets — and find a love of their own while they’re at it.

The inspiration for the novel came from the title itself, the word “possession,” Byatt told Wachtel in a 1990 interview on the first season of Writers & Company.

“It slowly began to develop all sorts of other resonances,” she said.

“I started thinking about how obsessed the Victorians were with seances and spiritualism and the voices of the dead speaking through the voices of the living medium in that sort of way. And then I thought of the poet Robert Browning, who is one of the people I most admire and love and how he wrote poems about many, many periods and many, many voices, all of which he felt were somehow speaking through him.

“And I thought that you could sort of compare the spiritualist silence with Browning’s poems as a way of the voice of the dead speaking through the living.”

The sexual connotation of the word “possession” was also key in the plot’s development.

“I thought, if I had not one poet but two poets, male and female, in love with each other, then there would be that sense too, in which they came to possess each other,” she said. “And after that, I got the idea of having two scholars, male and female, who came to possess both the poets and finally each other.”

A literary legacy

After the success of Possession, a bestseller that was eventually adapted for the screen, Byatt was hit with a flurry of creativity, writing novels, short stories and novellas, demonstrating her prowess for writing compelling fiction at all lengths.

She completed her tetralogy with Babel Tower and A Whistling Woman and was shortlisted for yet another Booker Prize for her 2009 novel The Children’s Book, which won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize. Some of her other celebrated works include novellas Angels and Insects, novel The Biographer’s Tale and short story collection The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye, which inspired the feature film Three Thousand Years of Longing starring Idris Elba and Tilda Swinton.

Byatt’s most recent book was a 2021 collection of short stories titled Medusa’s Ankles: Selected Stories.

In addition to book prizes, she also received awards and titles for her literary contributions as a whole; she was appointed to the Order of the British Empire in 1990 and was made a dame in 1999. In 2016, she was awarded the Erasmus Prize for her exceptional contribution to literature and in 2018, she accepted the Hans Christian Andersen Literature Award.

Regardless of her many accolades, it’s Byatt’s true love of writing and storytelling that shines through in her pages and will see her remembered by history.

In her 2009 interview with Writers & Company, she explained that she saw no point in writing stories if they don’t give pleasure.

“Somebody who writes fiction is making a world with which people can understand the world,” she said. “Then if they want to go and change the world, they can, but it’s not the same as setting out with a mission.”

“I’ve never had a mission. I wouldn’t know where to find one,” she said, inciting a roar of laughter from the Montreal crowd.

But by mission or not, Byatt has left behind an astounding literary legacy.

With files from Writers & Company and Melissa Gismondi

If you or someone you know is struggling, here’s where to get help:

This guide from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health outlines how to talk about suicide with someone you’re worried about.