Michael Bishop, who has died aged 78, wrote many stories that inhabit the borderlands between science fiction and mainstream, drawing on influences as diverse as Ray Bradbury and Jorge Luis Borges, Thomas M Disch and Philip K Dick, Dylan Thomas and Tolstoy, but also reaching back as far as the Greek historian Herodotus for inspiration. The common element in his work was a desire to explore the human spirit.

Early examples were set in vivid alien and alienating faraway worlds, such as his debut novel A Funeral for the Eyes of Fire (1975, revised as Eyes of Fire, 1980), set among the androgynous inhabitants of distant Trope. In Transfigurations (1979) a scientist tries to unravel a seemingly irrational alien culture.

Bishop introduced the Urban Nucleus of Atlanta, a domed city that represented an alternate, isolated US, and told its century-long history through A Little Knowledge (1977) and Catacomb Years (1979), the two books revised and combined in The City and the Cygnets (2019). Also known as the UrNu cycle, its scenes of racial tension and protesters beaten by authorities are still relevant.

As the Star Wars films, beginning in 1977, gave a juvenile form of science-fiction ascendancy, Bishop turned from off-world settings to paleoanthropological topics, telling Nick Gevers for the InfinityPlus website in 2000: “Rightly or wrongly, I wanted to reclaim [science fiction], at least in some of its literary manifestations, as a legitimate medium in which to examine age-old human concerns.”

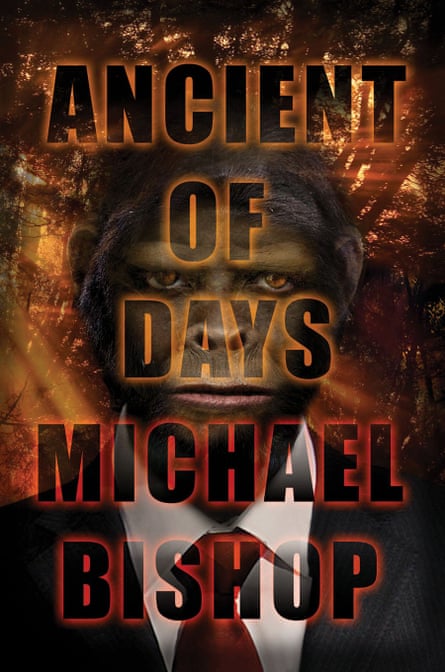

His novelette The Quickening (1981) won a Nebula award, and a second followed for the novel No Enemy But Time (1982), which threads together two narratives, one told by Joshua Kampa, an African American who travels back 2m years into the past, the other revealing Kampa’s journey from childhood, when he was named John Monegal by adoptive parents and haunted by vivid dreams of an ancient world, to becoming an amateur palaeontologist offered the use of a time machine. Ancient of Days (1985) reversed the direction of travel, with an early hominin surviving to the present.

His own favourite from among his novels was Brittle Innings (1994), a homage to both Mary Shelley and baseball in which a promising young player joins a Georgia team and meets their star, the statuesque and grotesque Jumbo Henry Clerval, an enigma revealed to be the immortal creation of Dr Frankenstein. The inventor’s creator herself starred in The Unexpected Visit of a Reanimated Englishwoman, Bishop’s “narrative introduction” to the collection The Mortal Immortal: The Complete Supernatural Short Fiction of Mary Shelley (1996).

Another homage was Philip K Dick Is Dead, Alas, originally published as The Secret Ascension (1987) but later reprinted under Bishop’s preferred title, in which Dick’s sci-fi novels are suppressed by President Nixon.

Ever the experimenter, Bishop also wrote the horror novel Who Made Stevie Crye? (1984); Unicorn Mountain (1988), which wove fantasy with Native American lore; the superhero satire Count Geiger’s Blues (1992); and a children’s book, Joel-Brock the Brave and the Valorous Smalls (2016). He collaborated with the British sci-fi writer Ian Watson on the novel Under Heaven’s Bridge (1981), and Paul Di Filippo for two crime novels, Would It Kill You to Smile? (1998) and Muskrat Courage (2000), under the name Philip Lawson. He also published two volumes of poetry, an essay collection and, away from sci-fi, two (mostly) contemporary story collections.

Born in Lincoln, Nebraska, Michael was the son of Lee (Leotis) Bishop, a farmer before enlisting in the US Air Force, and Mac (Maxine, nee Matison), a telephone operator.

The family moved around the US and the Pacific, including Korea and Japan, for Lee’s service. Michael spent a year at Yoyigi elementary school in Tokyo before his parents separated and he and Mac returned to the US. But Michael spent his summers wherever his father was posted.

His parents divorced in 1951, and, following a further marriage and divorce, Mac married Charles Willis, a former bomber pilot, who had two children of his own. In 1958 the family moved to Tulsa, where Michael attended Nathan Hale high school.

Willis was a fan of UFOs, pulp magazines, and sci-fi and horror movies; Michael favoured Classics Illustrated and the novels they were based on until a high school friend recommended Bradbury. While recovering from a footballing injury, Bishop began writing stories (“gritty urban fragments”) and poetry (“bad”), and outlined two novels about wolf-dogs inspired by Jack London’s White Fang.

He majored in English literature at the University of Georgia, took creative writing classes and met Jeri Whitaker, whom he married in 1969. On graduating with an MA in 1968, he applied to the Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps and taught English, first at the USAF Academy preparatory school in Colorado Springs, then, from 1972, at the University of Georgia.

Bishop sold his first story, Piñon Fall, to Galaxy in 1970, and sales to the Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, If and various anthologies followed.

In 1974 he moved his family to Pine Mountain, Georgia, to write full time. From 1996 to 2012 he held a post as writer-in-residence at LaGrange College.

His son, Jamie, who provided the artwork for five of Bishop’s books, was killed during the mass shooting at Virginia Tech in 2007. Bishop is survived by Jeri, his daughter, Stephanie, and two grandchildren.