In the spring of 2020, I was beating my head against the fourth draft of a novel that wasn’t working. Provisionally titled The Change, the story juxtaposed the acutely existential crisis of postmenopausal life against the backdrop of the chronically existential crisis of climate breakdown. My protagonist and first-person narrator, Rachel Calloway, was a 53-year-old journalist, childless and single, sober- and single-minded. Like all my protagonists, she was, in some ways, my fictional avatar, a person I might have been in another life. But the problem with the novel was that it kept running out of steam halfway through, and I couldn’t figure out how to fix it.

In my earlier first-person novels, I typically relied on a simple process wherein the architecture of the narrative emerged organically from the main character’s choices. Structure and character were inextricably linked in my mind, symbiotic even. This strategy created a lot of comic energy, since the narrators of these novels tended to be antiheroes full of mischief, constantly shooting themselves in the foot and making questionable, sometimes self-destructive but all-too-human decisions that ran counter to their self-interests.

The affectless detachment of the novella’s antihero, Meursault, offered me the philosophical equivalent of the Gallic shrug.

But Rachel wasn’t like them. She was a grown-up, a self-aware adult woman whose sole, stubborn interest was in the truth and nothing but. No matter what alterations I made in each subsequent revision, or what I threw at her, she kept pragmatically, stoically solving her existential crises, all of them: her complicated grief for her dead mother, her professional obsolescence, her clear-eyed despair about the environmental breakdown. She kept figuring out her shit and moving on with her life too soon, draining all the energy out of the plot. I couldn’t find the heart to force her to suffer to the end through all the terrible things I’d unleashed on her.

Maybe this was because I was struggling with many of the same things she was, and I wished I had some solutions. So I gave them to Rachel instead. Like her, I found myself at the tail end of a process that used to be called, euphemistically, The Change. Menopause was like going through puberty in reverse. When I finally got off the hormonal and emotional rollercoaster ride at 53, I felt as if I’d been returned to my preadolescent, undrugged brain. But I also feared professional dwindling and was now facing my own mortality in a whole new way.

Maybe because of this newfound clarity, I was unable to soften the hard surfaces of the inside of my own head, dim the lights a little, ease the despair. In the grip of that increasingly pervasive mental malady known as “climate grief,” I lay awake at night, my brain exploding over and over with the untenable knowledge that life on earth as we humans knew it was fucked forever; there was nothing to be done to stop what was coming, only to mitigate the very worst of it, and only if we were proactive and lucky. I felt as if we were all collectively staggering across shifting, disintegrating terrain, getting nowhere because there was nowhere left to go

And so, on a beautiful spring day in 2020, a bleak time at odds with the blossoms and snowmelt, many of us in the northern states in lockdown during the fourth year of Trump’s dark presidency, I found myself pulling an old paperback copy of Albert Camus’ The Stranger off the bookshelf. Given the state of things, I had a sense that it might be the literary touchstone I needed, the solution to my own novel’s irksome problems.

I hadn’t read Camus since college, back when I was a Francophile and inhaled L’étranger in French. All through the decades that followed, I retained the linguistic impression of a deeply unsettling absurdism so palpable it was as if the pages emanated a strong, slightly acrid smell. In those days, we were in the grip of a different kind of existential fear—the Reagan era’s nuclear nightmare of the Cold War. The affectless detachment of the novella’s antihero, Meursault, offered me the philosophical equivalent of the Gallic shrug—tant pis, this is the way things are, suck it up and get on with it. I found this perversely bracing at the time.

Now, thirty-five years later, my French rusty, I reread The Stranger in English. I was startled to recognize the parallels between it and my own novel. Like Meursault’s, Rachel’s mother has just died when the book opens, and she’s also forced to go back to the place she left a long time ago, a place where nothing good happens. Rachel’s stoic outlook on life echoes Meursault’s own resigned shrug: “After a while you could get used to anything.” For Rachel, a working-class Mainer who’s toiled long and hard to escape the poverty and neglect and addiction of her upbringing, existential despair acts as a kick in the ass.

Then I came to the end, where Meursault stares down execution, saying, “It was as if that great rush of anger had washed me clean, emptied me of hope, and, gazing up at the dark sky spangled with its signs and stars, for the first time, the first, I laid my heart open to the benign indifference of the universe.” Eureka! That was the answer to my novel’s structural problems.

It was just the old stages of grief repeating themselves, like a five-course prix-fixe menu that never changes, from anger to acceptance. Meursault wasn’t postmenopausal, and Rachel’s own impending execution—the inevitable death we all face at some point—was of a totally different kind, but it didn’t matter, Rachel could have said this as easily as Meursault: “I had lived my life one way and I could just as well have lived it another. I had done this and I hadn’t done that. I hadn’t done this thing but I had done another. And so?”

Yes, I thought, and so? Since it didn’t matter what Rachel did or didn’t do, and death was inevitable, why not cold-bloodedly ramp up her suffering instead of easing it, accelerate the calamities, make her life increasingly dire and hopeless? I was suddenly interested to see what she would do in response. I wrote a whole new draft, forcing myself to stay true to my own current, brutal vision of the world.

Of course, no one ever makes it out alive. That’s just the way things are.

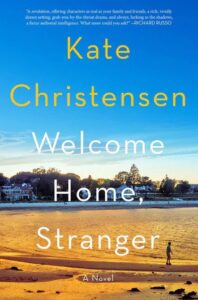

And in her darkest hour, my fictional avatar surprised me. As I wrote the last section of the new draft of the novel—now called Welcome Home, Stranger in a nod to Camus—I felt an unexpected uplift, and not only because the narrative arc was finally structurally sound. I had also somehow written both Rachel and myself through our shared dark fears of post-reproductive obsolescence and hopelessness in the face of impending global catastrophe.

I’d been trying to avoid facing it all head-on. That was why the novel hadn’t been working. That had been the problem all along. But of course, the only way to the other side was straight through, like sending Rachel through a nightmare car wash with abrasive brushes, scalding water, and caustic lye.

For me, this is a wholly new way of constructing a first-person narrative. Instead of setting loose upon my fictional world a mordant misanthrope or floundering but determined romantic, whose internal reality, at odds with the world, generates the impetus of the story, all the trouble and conflict was now externalized, coming from the world itself.

In other words, shit flies at the narrator too fast for her to keep up with it and threatens to bury her, and her reactions and responses are the driving engine of the book. This feels truer to this particular time in history, an era I call “the Terrible Twenties.” From a dramatic standpoint, it’s also more interesting; I’m too old to screw around with fuckups anymore.

At the end of The Stranger, Meursault pays with his life for the crime he commits, but Rachel, innocent of any crime, doesn’t get off so easily; there’s no escape into death for her. Like me, she still has work to do. We female elders, with our residue of estrogen—the empathy drug—and our hard-earned perspective and experience, are a valuable human resource, even if we can’t give birth, or maybe especially because we can’t. Our purpose might be to teach others how to weather the coming storms, having weathered so many of them ourselves, to help the young persist and adapt and survive—whether we want the gig or not.

Of course, no one ever makes it out alive. That’s just the way things are: tant pis. So we might as well suck it up and get on with it.

__________________________________

Welcome Home, Stranger by Kate Christensen is available from Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.