Ron Dungan

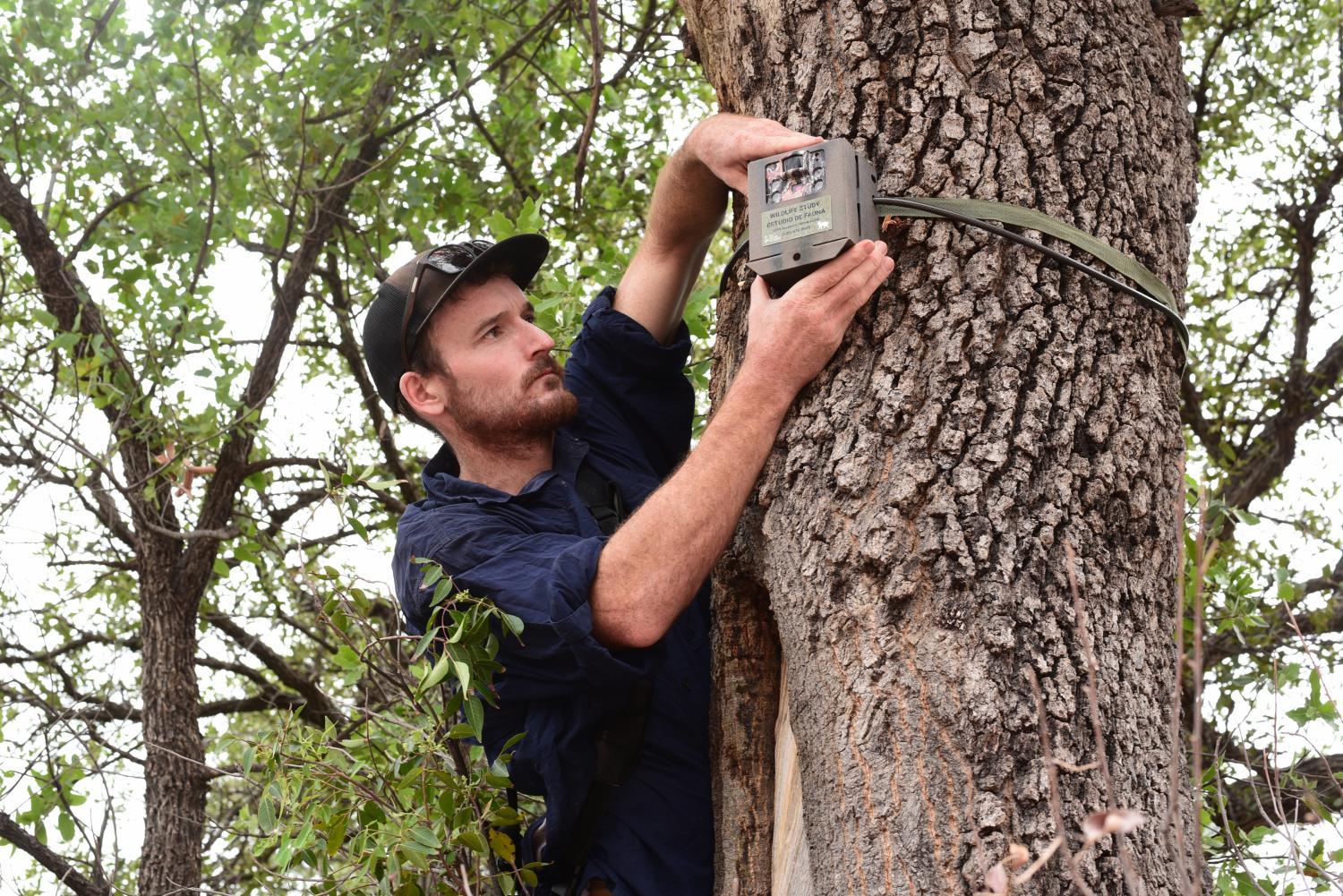

Eamon Harrity checks a wildlife camera near the border in southern Arizona.

Eamon Harrity drives a beat up Toyota pickup in southern Arizona. It’s late summer, and a storm swept through the region the night before. As we pass through the desert grasslands, clouds break over the Huachuca Mountains to the north, and over Mexico to the south. The mountains are what make this region unique. They’re called “sky islands.”

“They’re these high mountains that sprout from desert lowland seas if you will,” Harrity said. “So they’re higher elevation habitats surrounded by hot, arid, Sonoran Desert environments.”

Harrity works for the Sky Island Alliance, a nonprofit that focuses on these southern Arizona ecosystems, which are home to deer, coyotes, bobcats and other species. Parts of sky island country brush up against the border, where the government started building a wall during the Trump administration. Nearly two decades ago, Congress gave the Department of Homeland the authority to waive environmental laws to build barriers and roads near the border.

The Alliance has installed cameras to see how the changes might affect wildlife migration.

They take tens of thousands of photos every month. As he replaces batteries and memory cards, he flips through the camera’s monitor.

“Yeah, so here’s a whitetail deer. Yeah, these cameras are looking at wildlife movement in the region, specifically, how do animals navigate the infrastructure on the border?”

He’ll review the images on his computer later, but for now he makes a quick pass through them and spots raccoons, javelina and other animals.

“Oh, that’s cool. We have a black bear, crossing from Mexico, coming up, kind of ambling up across the road, looking east and west as he gets to the north side of the road and he disappears right up this wash.”

The cameras capture anything that moves: floods, butterflies, windblown leaves. They have thousands of pictures of cattle.

“Oh, here’s crazy rainstorm. It’s such a fun adventure to roll through the cameras because you never know what you’re going to get. It feels a little bit like a scavenger hunt as you’re flipping through the photos, keeping an eye out for what fun creature might be there.”

What they don’t see a lot of is people.

When people meet wilderness

Ron Dungan

A Normany barrier along the U.S.-Mexico border southern Arizona. The barriers stop vehicles from crossing in remote areas.

“Over the last three years in the San Rafael Valley, it’s just been over 1,000 detections of people,” said Emily Burns, program director for the Alliance. “Seventy-five percent of that have been Border Patrol. So actual law enforcement or construction crews that are working on the border infrastructure itself.”

They also spot hunters, or cowboys on horseback.

“But it’s very rare that we see people that have likely crossed, walked over the border,” Burns said.

The Border Patrol has the legal authority to waive environmental laws to build infrastructure. But it can conduct its own environmental reviews, and does so frequently.

“So we make sure to consult with biologists with the federal land agencies, to see how to best mitigate a lot of the impacts that we know our infrastructure is going to have,” said Pete Bidegain, of the Border Patrol.

He works with the Sky Island Alliance and other nonprofits, as well as federal agencies that manage lands near the border.

“When they had proposed to us to place these cameras along the border to monitor these small wildlife passages, we consulted with the federal land management agencies in those areas to ensure that Sky Island Alliance had the proper permits in place,” Bidegain said.

Gathering photos, gathering data

Ron Dungan

Eamon Harrity takes a moment while storm clouds pass over the Huachuca Mountains in sky island country.

After talking with conservationists, the agency created small openings in the bollard style wall that went up during the Trump administration. They’re about the size of a piece of paper, and can allow small animals to pass through.

“For me personally, I grew up in southern Arizona. I think it’s really important to protect what we have and so any time that I’m seeing some sort of cool animal, captured on camera, you know doing well and thriving here in Arizona, I can appreciate that,” Bidegain said.

Burns, the program director, says that’s exactly the kind of thing she hopes to accomplish with this project.

“While we hope that the data will be hard hitting and convince policy makers to change border policy, more than anything we hope that people see the images of the wildlife living at the border and fall in love with the wildlife, like we have,” she said.

The animals live in remote stretches of wild ground, a detail that can get lost in the daily news cycle, which at times can give the impression that the Arizona border is being overrun. Although some places do have high concentrations of traffic, most of the state’s southern deserts are empty stretches of wilderness. You can walk for hours near some stretches of the border in southern Arizona and never see another soul.

“It’s very rugged landscape,” Burns said. “And you’re dozens of miles from the first major highway.”

When the government started to waive environmental laws to expedite construction, the Alliance started to document animal behavior in the region.

“At that time, it was happening so quickly, there hadn’t been environmental studies to document which species are living and moving across the border in this area that was threatened by border wall construction,” Burns said.

They’ve photographed thousands of animals. Ken Madsen, of the Ohio State University, studies migration issues. He says that rhetoric about border crossing can get overblown.

“It is relatively quiet,” Madsen said.

When the cameras do pick up people, it’s usually Border Patrol, or construction crews working on the wall. But people do cross, even in remote, difficult areas.

“Clearly, some people and some drugs pass through the region, you know, obviously,” Madsen said.

A less-rugged landscape

Sky Island Alliance

A white-tailed deer photo captured by Sky Island Alliance cameras.

Years ago, policy makers thought the rugged terrain would serve as a wall of sorts. And it did, up to a point. The government built what’s known as Normandy barriers to keep people from driving across. During the Trump administration, the government started work on a bollard-style wall, with metal posts every four inches. Analysts say the project led to more roads along the border. In other words, the landscape became less rugged.

“The irony is that all those improved roads are being used by traffickers and migrants as well as Border Patrol. Essentially you have provided access where access didn’t exist before,” Madsen said.

Conservationists say the bollards stop animals, but not people. They’re also concerned about stadium lights that have gone up along the border, in places such as Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. That could affect the behavior of nocturnal animals. Bidegain says the agency works with conservation groups on a regular basis.

“Protecting the environment is one of our key responsibilities when it comes to CBP and working together with our federal land managers,” Bidegain said.

He says there are no plans to turn on the stadium lights in remote areas at this time. Some of them haven’t been wired.

“As for lighting along the border in the Tucson Sector, outside of the urban areas, there’s not a plan to turn on the lights,” he said.

Border wall construction may restart

Ron Dungan

Eamon Harrity checks a wildlife camera near the U.S.-Mexico border.

Over the years, the government has found that building a wall is a learning process. They’ve learned to build gates in creeks and drainages, which stay open during the rainy season and closed later.

“To help facilitate that in a lot of these riparian areas that are really precious to southern Arizona, we have flood gates in place that we open up in flood season, to allow water to go through and not cause damage to CBP border infrastructure,” Bidegain said.

Conservationists say it’s important to see how animal traffic changes over time. The information could become even more important in the face of climate change.

“This video shows a deer walking up to the barbed wire fence, and apparently it ducks under the vehicle barrier but decides it can’t get under the barbed wire fence and turns around,” Harrity said.

Animals may need to migrate more as the warming planet creates changes to water sources and habitat.

“Animals need, you know, resources, food and water and shelter, essentially, habitat, to exist. And they need mating opportunities, and they need to be able to move freely to access those things,” Harrity said.

Border wall construction stopped after President Joe Biden took office. But Congress has kept funding for it in place, and the administration recently resumed building in Texas. Conservationists in Arizona hope that it doesn’t resume here.

More stories from KJZZ

Ron Dungan

Eamon Harrity checks a wildlife camera by a Normandy barrier on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Ron Dungan

A Normandy barrier and barbed wire fence on the U.S. Mexico border.

Sky Island Alliance

A black bear photo captured by Sky Island Alliance cameras.

Sky Island Alliance

An American kestrel photo captured by Sky Island Alliance cameras.

Sky Island Alliance

A coyote photo captured by Sky Island Alliance cameras.

Sky Island Alliance

A javelina photo captured by Sky Island Alliance cameras.

Sky Island Alliance

A mountain lion photo captured by Sky Island Alliance cameras.

Sky Island Alliance

A pronghorn photo captured by Sky Island Alliance cameras.

Sky Island Alliance

A roadrunner photo captured by Sky Island Alliance cameras.

Sky Island Alliance

Sky Island Alliance photo of border wall construction.