Half a century on, Kohoutek may be due a little more respect. Though it disappointed the media and the public, it proved to be a bonanza for serious scientists.

Illustration by Meilan Solly / Images via Wikimedia Commons, Newspapers.com and New York Times

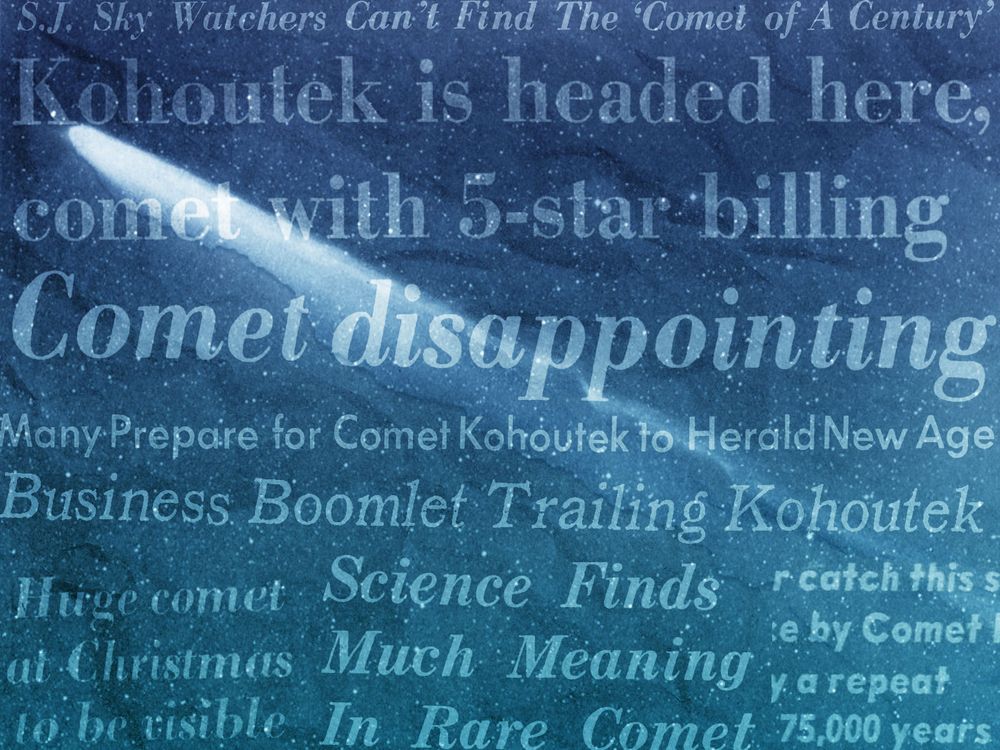

Fifty years ago, in late 1973, a recently discovered comet, hurtling toward Earth at nearly 200,000 miles an hour, became an international celebrity. Kohoutek, as it was named, wasn’t your everyday space rock, but rather a huge, unusually bright comet predicted to put on a dazzling display that would be visible to the naked eye around Christmastime. Its tail was expected to stretch for 100 million miles. One top NASA scientist called it “the most important comet in history.”

Kohoutek became the subject of almost daily news reports. It was featured on magazine covers and celebrated in song by artists from Burl Ives to Pink Floyd. Fans scheduled parties to watch the skies, amateur astronomers crowded onto the top of the Empire State Building, and department stores sold out of telescopes and binoculars. The ocean liner Queen Elizabeth 2 took to the seas for a better view, with a passenger list that included writer Isaac Asimov and Luboš Kohoutek, the Czech astronomer who discovered the comet.

Luboš Kohoutek briefs the press in January 1974, when the comet made its closest approach to Earth. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Fringe religious groups and assorted eccentrics adopted the comet as their own, some saying it was a giant spaceship come to scoop up the faithful before the world came to an end. A cult known as the Children of God demonstrated at the United Nations building in New York to warn about the comet its members called the “Christmas monster.” Snoopy expressed similar fears in a “Peanuts” cartoon and put a sack over his head just in case.

In the end, Kohoutek was a spectacular bust. It wasn’t nearly as bright as expected, and most people couldn’t see it at all due to cloudy skies, city lights and other issues. Aboard the QE2, Kohoutek (the man) thought he might have caught a faint glimpse of it, but even he wasn’t sure.

Once hyped to the skies, Kohoutek now became an international object of ridicule. One columnist called the comet the “Edsel of the firmament,” after a notoriously unsuccessful Ford automobile of the 1950s. Others have likened it to such memorable duds as New Coke, the 1962 New York Mets and presidential contenders who started strong but flamed out in the primaries.

But half a century on, Kohoutek may be due a little more respect. Though it disappointed the media and the public, it proved to be a bonanza for serious scientists.

A color photograph of Kohoutek, taken by staff at an Arizona observatory with a 35mm camera on January 11, 1974 Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

In the beginning …

Kohoutek, the astronomer who would soon lend the comet his name, discovered the celestial body while working at an observatory in Hamburg, Germany, in March 1973. As is often the case in science, he was looking for something else at the time: a long-lost comet that hadn’t been seen since the 19th century.

Just a “faint, fuzzy spot” in the photographs Kohoutek had taken through a 32-inch telescope, the new comet was unusually bright given its distance, some 400 million miles from the sun. This luminous glow suggested that as the icy object continued its journey, it could become one of the brightest comets ever visible from Earth.

The comet of the century

The general public first learned about the coming comet in April 1973, when a brief Associated Press article reported that “a newly discovered comet will be near the sun next Christmas and could be the most spectacular astrophysical event of the century, astronomers say.”

In the months that followed, media reports continued to foreshadow Kohoutek’s expected visit, even as it vanished from sight due to its orbit. It was only in late September that a Japanese astronomer again caught sight of the comet. Kohoutek mania was about to begin.

A December 1973 newspaper article accompanied by a photo of a woman with a Kohoutek T-shirt Newspapers.com

By early November, Newsweek was promising readers “the celestial extravaganza of the century.” Time, one of many magazines to feature the comet on its cover, called it “a reminder of great events—and even greater mysteries—far beyond Earth.”

NASA announced that it would be sending its next team of astronauts to the Skylab space station to give them a view of the comet unobstructed by Earth’s atmosphere. The trio blasted off on November 16 as part of the space agency’s Operation Kohoutek, which also involved uncrewed satellites, balloons, rockets and other aircraft, as well as ground-based observatories.

A bit closer to Earth, the Hayden Planetarium in New York City reportedly planned to charter a Boeing 747 for a special six-day “Flight of the Comet” but had to cancel the trip because of fuel shortages. Tickets would have cost the then-astronomical sum of $1,750 (around $12,000 today).

The Cunard Line announced that its QE2 would set sail from New York on December 9 for a three-day cruise off the coast of the United States, with tickets priced between $130 and $295 (roughly $900 to $2,050 today). Though the cruise line promised passengers the “greatest comet of the century, from the greatest ship in the world,” cloudy skies kept them from seeing much of anything. Still, that didn’t stop Cunard from scheduling another comet cruise for the following month, this time inviting astronomer Carl Sagan and astronaut Buzz Aldrin along for the ride.

Astronomer Luboš Kohoutek calls astronauts at the Skylab space station during the passage of the comet in January 1974. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, a 32-year-old Wisconsin man who maintained that the comet was actually an alien spaceship in disguise offered 1,000 tickets at $10 apiece for anyone who wanted to join him in boarding it when it arrived. He said that an angel had visited him some months earlier and told him he’d get to be the ship’s captain.

Entrepreneurs of all sorts, knowing an opportunity when they saw one, began churning out Kohoutek T-shirts and commemorative knickknacks. The New York Times reported that telescope sales in the Big Apple were up 300 percent, despite warnings from some astronomers that the combination of bright lights and air pollution might make Kohoutek impossible to see from metropolitan areas.

Astrologers now joined astronomers in sharing their insights. Newspaper psychic Irene Hughes predicted that, among other calamities, the comet would bring higher taxes and “shortages of everything.”

David Berg, leader of the Children of God religious cult, issued numerous apocalyptic warnings, urging people to flee the U.S. before January 1974, when “some kind of disaster, destruction or judgment of God is to fall because of America’s wickedness.”

Timothy Leary, a former Harvard University psychologist turned psychedelic drug guru, saw Kohoutek as a message from the extraterrestrial beings he believed “seeded” Earth with life billions of years ago. He even renamed it Starseed. “The Comet Starseed,” he wrote, “is a reminder that we are not earthlings, that we come from outer space, that we are members of the galactic family.” Leary was imprisoned in California at the time on an assortment of charges, and supporters held Kohoutek-themed benefits, called “comethons,” to raise money for his release.

Kohoutek, as seen from Skylab in December 1973 Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

In what may have been a disappointment to the doomsday prophets, Kohoutek never got any closer to the sun than 0.142 astronomical units, or 13.2 million miles, on December 28, 1973. Then it began to return from whence it came. In its wake, Kohoutek left behind a few memorable photos, some taken by the Skylab astronauts, and more than a few red faces back on Earth.

When the New York Times published a guide to Halley’s Comet ahead of its 1986 flyby, the writers began with a plea to the cosmic gods: “Please, whatever happens, don’t let it be another Kohoutek.” They continued, “Kohoutek—one hesitates to speak its name—was, of course, a fiasco.”

But was it really?

Why Kohoutek was unappreciated and underestimated

Kohoutek “received so much advance publicity and so little post publicity that few except those involved ever heard the end of the story,” wrote Fred L. Whipple, director of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory and an astronomer at Harvard University, in a 1975 paper.

But the scientific community had been toiling away. In June 1974, a few months after Kohoutek faded from the skies and the news, scientists presented 42 papers based on their findings at a workshop hosted by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. That was just the beginning. Today, a search on Google Scholar for journal articles relating to Comet Kohoutek yields more than 4,000 results.

Whipple may have been enthusiastic about Kohoutek for another reason. It helped confirm his famous theory, first advanced in 1950, that a comet was “fundamentally a ball of dirty ice activated by solar radiation.” His “icy conglomerate” model—or “dirty snowball” theory, as it is more commonly known—maintained that comets consist of frozen water sprinkled with rock rather than rocks or sand held together by gravity. When a comet approached the sun or another star, the ice would begin to vaporize, creating the trails of water and dust that make up the comet’s tail.

While astronomers could infer from their observations that comets contained water, Kohoutek marked the first time “water was directly detected in a comet,” says Geza Gyuk, director of astronomy at Chicago’s Adler Planetarium and a visiting scholar at the Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics at Northwestern University.

Illustration of Kohoutek on December 29, 1973, by Skylab 4’s Edward Gibson Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

This find wasn’t the only first associated with the comet. Kohoutek also marked the first direct detection of methyl cyanide, hydrogen cyanide and silicates in a comet. Confirming their presence “gave astronomers a much better understanding of what comets were made of,” Gyuk says. Because comets are thought to be relatively pristine, he adds, that “helps us understand the formation of the solar system and the processes that enrich the interstellar clouds that stars and planetary systems form from.”

These discoveries were made possible in part by the fact that Kohoutek was the right comet in the right place at the right time. It was a “new comet,” Gyuk points out, meaning its material had been undisturbed by solar radiation for billions of years. Additionally, it arrived at a time when astronomers had a raft of new tools at their disposal, in particular radio telescopes, which are far more sensitive than traditional optical telescopes.

Gyuk, who was 4 years old when Kohoutek swung by, compares the comet to another famous flop of the era: the Sony Betamax. Introduced in 1975, the cassette format competed with JVC’s VHS to become the standard for home video players. While many considered it superior technology, it lost the battle. “Sort of like the Betamax,” Gyuk says, “Kohoutek was very good, just not very popular.”

Earth may still have a chance to make amends with the unjustly derided comet. Kohoutek is due for a return visit in another 75,000 to 80,000 years.

Recommended Videos