The introduction of the Draft Broadcasting Services Regulation Bill, 2023 (Draft Bill), marks a significant shift in the regulatory approach taken by India towards over-the-top (OTT) streaming and digital news platforms available on the internet. The Draft Bill proposes extending traditional broadcasting regulations to digital publishing services, with requirements of mandatory registration, the establishment of content evaluation committees and adherence to common programme and advertising codes put in place for platforms across broadcasting mediums.

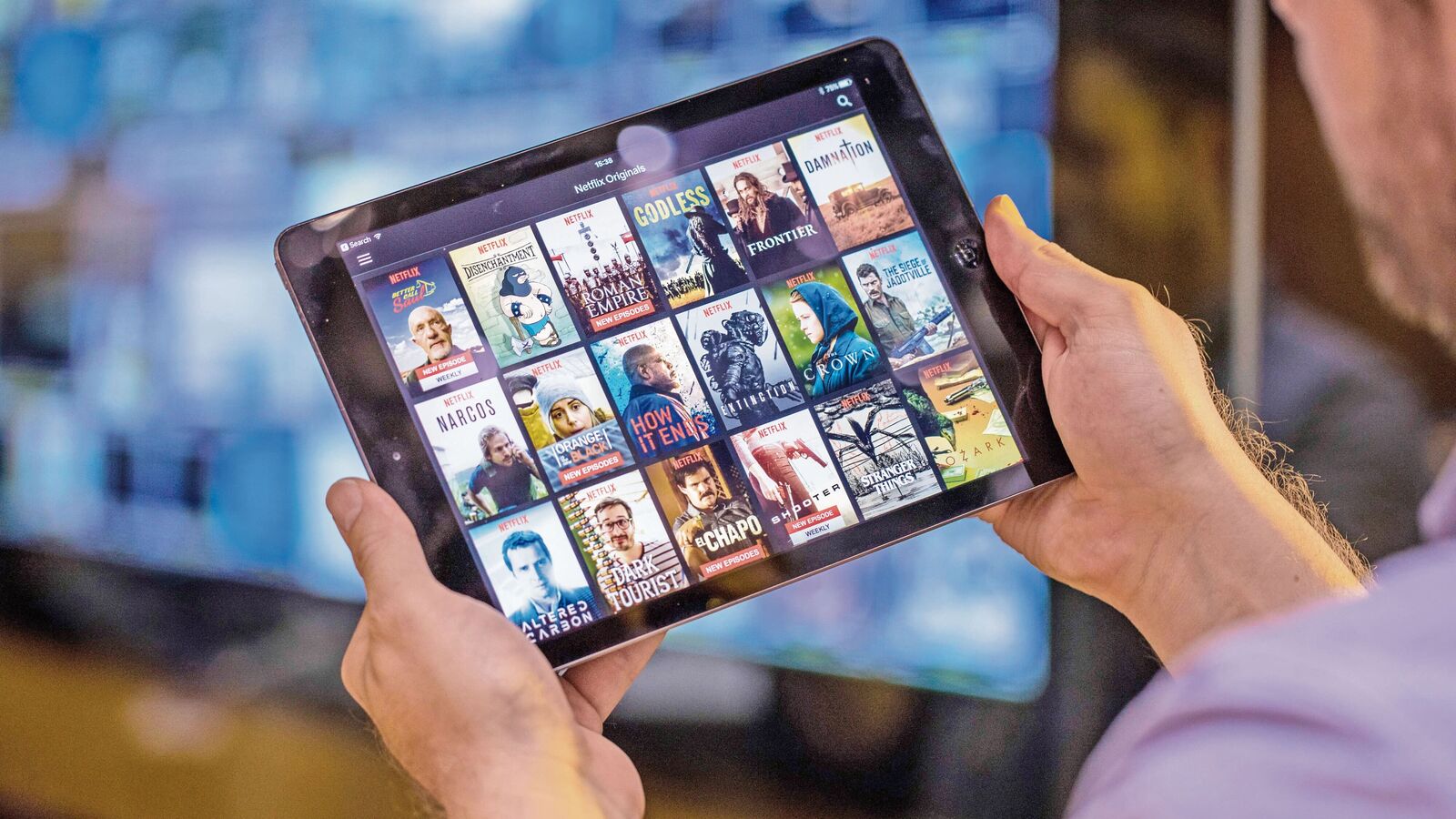

Imagine a world where every show you stream, every news clip you watch online and every podcast you listen to is regulated under the same stringent guidelines that govern your traditional TV channels. Will such a framework align with the doctrine of reasonable classification, considering that the underlying business models and content delivery mechanisms of OTT and digital news platforms differ substantially from TV and traditional films? How will this approach impact the dynamism of digital content creation? And most importantly, is it practically possible for one law to balance the drastically varied contours of digital publishing and traditional broadcasting?

The nub of the issue is this: Should OTT platforms be regulated the same way as traditional TV channels in India?

Across ecosystems, there’s a noticeable push to unify regulations for internet-based services and other technology mediums, exemplified by the Telecommunication Bill, 2022. Now, a parallel approach is being undertaken for traditional cable and film broadcasting versus OTT and digital news platforms. These convergence efforts pose critical questions about the feasibility and effectiveness of imposing a single regulatory framework on fundamentally distinct technologies and business models.

Let’s take a closer look. Traditional TV and cinema businesses operate on a ‘push’ model, which delivers content to bulk audiences at pre-determined times. In contrast, OTT platforms, which use tech advancements including an ability to ‘stream’ content from internet storage onto individual devices, are designed to ‘pull’ viewers in with choice, giving the users of their apps the autonomy to select what and when they want to watch from a wide range of content. This model has revolutionized content consumption, providing a platform for niche genres and unconventional narratives that may not find space in traditional TV, which must serve the needs of bulk audiences.

Regulating OTT platforms under a single broadcasting regulatory framework risks diluting the OTT model’s uniqueness, which is the ability to offer diverse, unorthodox and tailored content experiences. It may compel content creators to opt for safer, universally acceptable themes, which could limit creative freedom and diminish the rich tapestry of content available online to viewers.

What is the need for a whole new regulatory framework when India already has information technology rules in place that cover digital platforms? This is unclear, as most of the measures proposed in the Draft Bill are already covered under the IT Rules of 2021.

The proposed programme and advertisement codes appear to be a replication of the code of ethics that exist under the IT Rules, 2021. Existing research shows that these codes generally tend to be vague, leading to concerns about the chilling effect they could have on free speech. Our study showed that the vagueness in terms like “half-baked truth,” “indecency” and “obscenity” under the IT Rules’s Code of Ethics has revitalized portions of Section 66-A of the IT Act, which was struck down by the Indian judiciary in the Shreya Singhal judgement for vagueness.

The Draft Bill also proposes the establishment of content evaluation committees by all broadcasters to self certify their content. Digital publishers already undertake content rating exercises under the IT Rules, 2021. Research by The Dialogue based on industry feedback suggests that the current content rating process is working quite well. Further, extending the established norms further by mandating more onerous content evaluation procedures can be impractical on account of the unique nature of the ever-expanding internet. The web’s continuous influx of material, including news and other content on current affairs, is so voluminous that it is virtually impossible for any panel to effectively review and certify everything. Moreover, ensuring objectivity and similar standards of certification across all publishers can be a significant challenge.

Another significant aspect of the law that will come to bear if the Draft Bill is enacted in its current form is a three-tier system of grievance redressal, comprising a grievance officer at the broadcaster level, a self-regulatory organization at the industry level, and a government-led broadcast advisory council for oversight. This three-tier mechanism mirrors the self-regulatory system that currently exists under the IT Rules, 2021. And a primary impact assessment of the OTT ecosystem shows that, apart from a few concerns of principle, the three-tier regulatory mechanism under the IT Rules is functioning effectively.

Moves to re-invent the wheel should only emerge from actual needs and anticipated benefits—evaluated through thorough analysis and evidence-based research.