Some believe it’s a mystery why Walasse Ting did not have a solo exhibition in the United States before now.

“He was so central to so many critical narratives,” said NSU Art Museum curator Ariella Wolens.

“He does pop up, and it’s not like he’s completely disappeared,” Mia Ting, his daughter, told ARTnews. “But he’s never the focus of the conversation at all.”

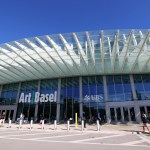

A colorful and wide-ranging retrospective of the Chinese American visual artist and poet might finally change that. The show, titled “Walasse Ting: Parrot Jungle,” opened on November 10 at the NSU Art Museum in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, a one-hour drive north from Miami, and sheds light on an artist who spent nearly five decades living and working in Europe and United States across several styles and movements, but whose impact and influence was often overlooked.

Walasse Ting, I Take Off My Pants Facing Sunset, 1969. Acrylic on canvas. 40.2 x 51.9 in / 102 x 132 cm. Courtesy of Private Collection, New York.

Jeffrey Sturges

Born in Shanghai in 1929, the self-taught Chinese American visual artist and poet moved to Paris in 1952 (with only $5 on hand) and then settled in New York in 1957. He would go on to make works that flirted with a number of different styles and genres: Abstract Expressionism, Pop art, nudes. He also produced poetry and painted with Chinese-style brushwork.

He crossed paths with artists ranging from Andy Warhol to Sam Francis to Joan Mitchell, and Tom Wesselman, Roy Lichtenstein, and Robert Rauschenberg were among those who contributed to 1¢ Life, Ting’s book of poetry and lithographs published in 1964, which is included in the NSU show. He racked up a number of accolades: he won a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1970, and his works have been acquired by institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art and the Centre Pompidou.

Walasse Ting, 1 ¢ Life, 1964. The Estate of Walasse Ting. Courtesy of NSU Art Museum.

But generally, Ting, who died in 2010 at 80, is not nearly as well-known as many of the artists who worked alongside him in postwar New York.

Perhaps for that reason, Ting’s daughter Mia described it as a total surprise that the NSU Art Museum wanted to organize a major retrospective of her father’s career. “I had never even heard of that museum,” she told ARTnews while helping to install an exhibition of her father’s work at Alisan Fine Arts‘s new location in New York. “Even the regional museums that have him in their collection, they’ve never expressed interest in doing anything.”

Nationally renowned museums have even held Ting’s work for a while. Looking for a Bee (1968), a splatter painting on loan from the Guggenheim Museum, is one of the many works in this exhibition that testifies to how Ting absorbed postwar styles and made them his own. With its splashes of green, the work recalls Pollock’s drip paintings. But Ting’s paint is even chunkier than Pollock’s, causing it to feel sculptural at times.

Walasse Ting, Miss World, 1975. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the NSU Art Museum.

Jeffrey Sturges

Critics praised other artists’ works that looked similar to Ting’s Looking for a Bee, but Mia said her father was not a self-promoter and didn’t get involved, which likely hurt his art career. “As exuberant and opinionated as my father was and his work, he was never the type of person to be like, ‘Look at me,’” she said. “He hoped his work would do that.”

Ariella Wolens, the NSU curator, noticed that Ting kept coming up in her research when she was organizing an exhibit on Pierre Alechinsky and Keith Haring. Referring to the former artist, she said, “They were incredibly close. And his impact was so overwhelming.”

According to Wolens, Ting taught Alechinsky about Chinese aesthetics, calligraphy, acrylic technique, working on paper, and a technique of adhering paper onto canvas called marouflage. Ting was close friends and collaborators with CoBrA cofounders Karel Appel and Asger Jorn, even after the group disbanded. The groundbreaking Martha Jackson Gallery, which also represented many other CoBrA artists, showed Ting’s work in solo exhibitions in 1959 and 1960.

“There hasn’t been this sort of ambassadorship with his work by anybody,” Wolens said, noting Ting’s subsequent lack of gallery representation since 1986. “So we’re sort of giving him an honorary space here, because it’s just one site that he had this close connection to among many.”

The title of the NSU Art Museum exhibition is a reference to Ting’s affinity for the Miami wildlife park Parrot Jungle. He documented the family’s trips there in hundreds of photographs and drawings. The excursions were part of annual journeys to West Palm Beach to visit Ting’s Jewish in-laws.

Walasse Ting, Untitled, early 1980s. Acrylic and Chinese ink on rice paper. 70 x 38 in / 177.8 x 96.5 cm. Private Collection, Hong Kong.

Courtesy of the NSU Art Museum

South Florida inspired many of the artist’s “neon-soaked visions” of naked women, colorful animals, and vivid flowers.

“He loved the hot weather,” Mia told ARTnews. “He loved all the fruit and the flowers and all this stuff. Could he have lived down there? No way. But going down a week out of the year, he loved it.”

Walasse Ting, Looking for a Bee, 1968. Acrylic on canvas. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

The exhibition also includes postcards, personal photographs, exhibition booklets, news clippings, poems, and other letters.

Wolens and Mia Ting both hope the exhibition at NSU Art Museum significantly raises awareness of the Chinese American artist and his legacy. They’re already seeing how Ting’s images of butterflies, cats, flamingos in bright colors have a noticeable impact on attendees. “I’ve rarely seen this happen with an exhibition, but people actually walk out of it happy,” Wolens said.