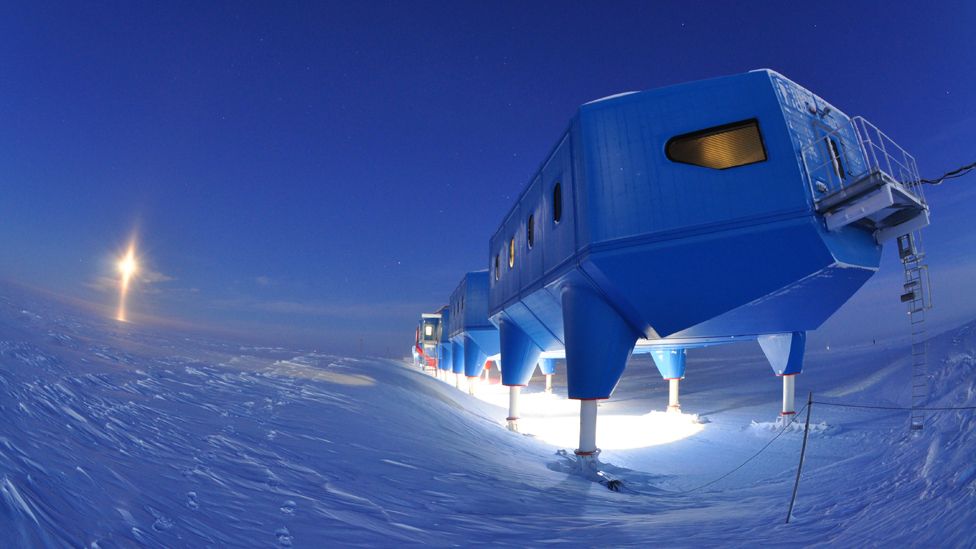

Scientists are closely watching the fast pace of a vast swathe of floating Antarctic ice that hosts a UK base.

The Halley station sits on the Brunt Ice Shelf, which has recorded an abrupt acceleration in recent months after calving giant icebergs.

There is no immediate concern the rest of the Brunt will break apart and doom the currently unoccupied base.

But British Antarctic Survey officials say greater stability must return before extended operations can resume.

‘Daily monitoring’

A decision to cease winter staffing was made seven years ago, with Halley now crewed during only the southern-hemisphere summer season, which begins in November. Forty people are due to visit the station, along with a ship carrying supplies.

Prof Dominic Hodgson said he was happy for this work to proceed.

“The shelf has given no suggestion that it’s about to fragment and pose an imminent danger to our infrastructure,” he told BBC News.

“And we’ll continue to do what we have done for the last few years, which is daily monitoring of the situation to see if any behaviour emerges that we hadn’t anticipated.”

- Thousands of penguins die in Antarctic ice breakup

- Polar seafloor exposed after 50 years of ice cover

- How a colossal block of ice became an obsession

Prof Hodgson, along with BAS colleague Dr Oliver Marsh and remote-sensing expert Prof Adrian Luckman, of Swansea University, have just submitted a report on the status of the Brunt Ice Shelf to online journal The Cryosphere.

The Brunt is an amalgam of ice, about 150-200m (500-650ft) thick, that has come off the Antarctic continent and pushed out into the Weddell Sea.

This buoyant mass has had an outward speed, historically, of 400-800m a year. But there has been a dramatic acceleration, from about 900m a year at the start of 2023 to 1,500m by August.

The data comes from precise GPS measurements around Halley and radar observations by the European Union’s Sentinel-1a satellite.

The acceleration follows the calving of two major icebergs from the leading edge of the Brunt – a 1,300-sq-km (500-sq-mile) behemoth called A74, in February 2021, and an equally mammoth slab called A81, in January this year.

A74’s impact was minimal but A81 appears to have released the shelf from a shallow section of seafloor that normally pins it in place and slows the seaward momentum.

What is more, these calvings – and there was another smaller one in June – have prompted new areas of stress in the ice shelf.

Prof Luckman said: “The Brunt has lost contact with this pinning point, known as the McDonald Ice Rumples, and, as a consequence, it has speeded up and is thinning. And you can actually now see cracks starting to open up at the grounding line (the zone where ice coming off the continent becomes buoyant), to the west and south of Halley.”

“How this will play out is anyone’s guess,” Prof Luckman added.

The latest data from Sentinel-1a indicates the shelf’s acceleration at the grounding line has faltered in recent days but continues to move at high speed, so rifts in the ice are probably still opening.

What does seem clear is the Brunt’s observed behaviour has nothing to do with climate change. There is no atmospheric or ocean data to suggest this is a factor.

‘Settle down’

The UK has had a base in various forms on the Brunt since the 1950s. Critical research has included the discovery of the ozone hole in the 1980s.

From time to time, Halley buildings have been demolished or abandoned when they have exceeded their maintenance lives or simply been buried in deep snow.

But the situation confronting the present, sixth iteration of the base is quite different and the possibility it might become stranded on a fragmented ice platform could not be totally ignored, Prof Hodgson said.

“The hope must be that a thicker section of the shelf eventually catches on the seafloor again to re-establish the old stability. And we can see from the geological record that these pinning points do get occupied and reoccupied. So it could all just settle down again,” he added.