On View

Weserburg Museum For Modern Art

NOW AND THEN

November 18, 2023–March 31, 2024

Bremen, Germany

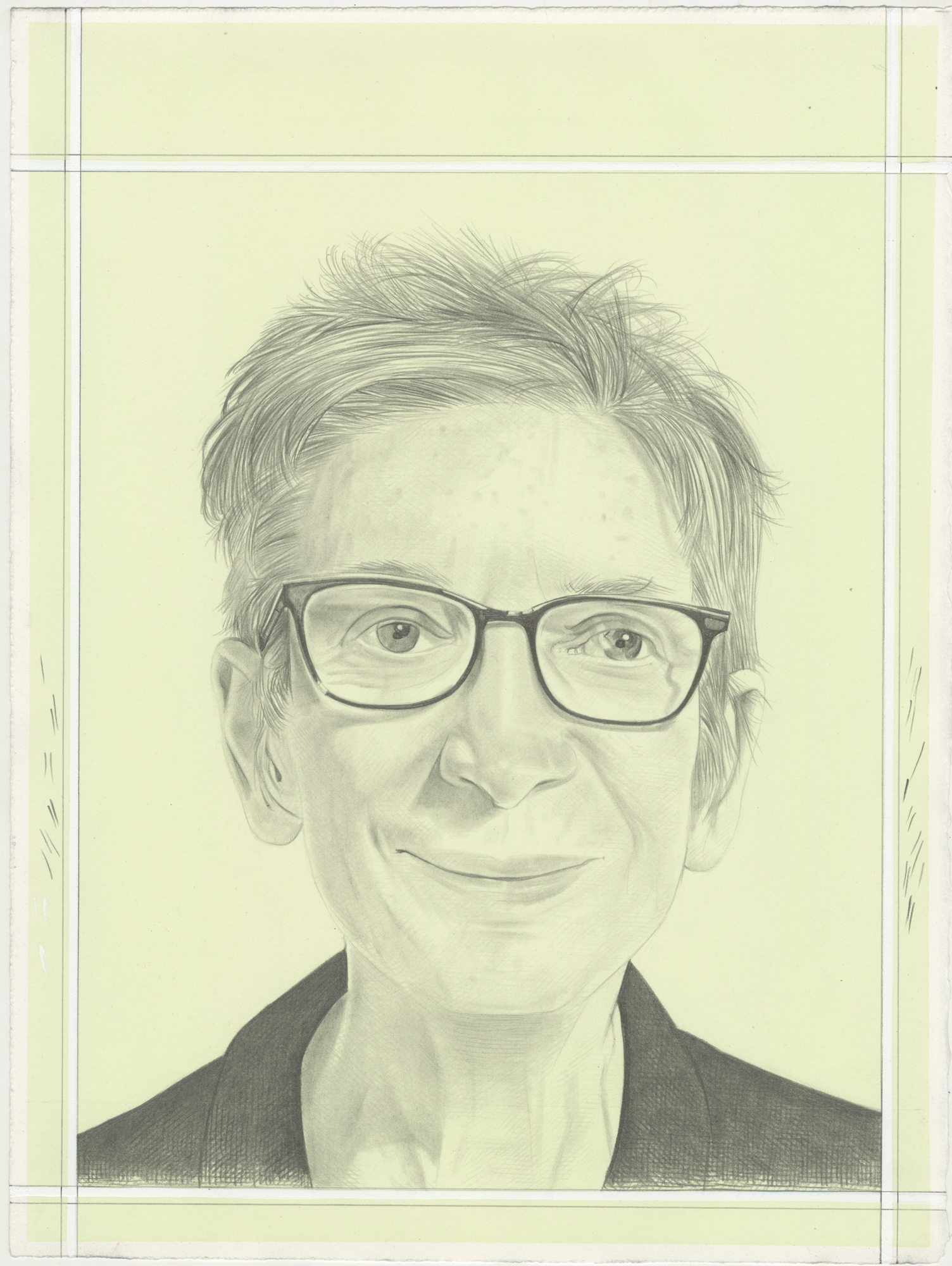

Kay Rosen and I have been in conversation for more than thirty years, beginning soon after I first saw her work at Feature Inc. in New York at the end of the 1980s. Our connection ever since has been built around both art and life, and not only because I was born in Indiana in 1965 just a few years before Kay—a native of Corpus Christi, Texas—moved to the Hoosier State to live and work. 1965 also happens to be the year she received her BA in Linguistics, Spanish, and French from Newcomb College of Tulane University. In 1968 she moved north to attend graduate school at Northwestern University to study Linguistics and Spanish. Kay’s subsequent decision to move away from linguistics to language-based art making opened the doors to what has become a more than fifty-year career of breaking or tweaking the rules of language, exponentially expanding its territory and meaning and the visual forms that give it shape. Twenty-five years ago, Connie Butler and I organized Kay’s first museum survey, lifeli[k]e, at the Museum of Contemporary Art and Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles. Now, as Kay’s first survey in a European museum has recently opened, we have added the following exchange to Kay’s brilliant legend.

Terry R. Myers (Rail): Because we’re doing the interview on the occasion of your first major institutional show in a museum in Europe—at the Weserburg Museum for Modern Art in Bremen, Germany—I wanted to ask you about its title, NOW AND THEN. What was on your mind?

Kay Rosen: Because the exhibition spans from 1984 to 2023, part of it refers to the time range. But the other part was that a lot of the works that were made a long time ago have some sort of relevance today. There’s enough open-endedness in them that they can be transported to other time periods and still make a certain kind of sense, not necessarily regarding the same issues that they addressed twenty or thirty years ago, but they can be relevant in a different way. Ingo Clauss, the curator, and I thought “Now and Then” seemed like a good way of encapsulating that reach.

Rail: It reinforces one of, if not the major thing about your work: the now and then—or the this and that—is about things that may be related, but still have a separation. And when we think of that separation, your work constantly just shatters it. The nowness and the then-ness are always there one hundred percent, each all at once. There’s a kind of magic to it. The now gets challenged, the then gets challenged, and what emerges from the now and then is the “what’s next?”

Rosen: Maybe the work is flexible enough, due to the reductiveness of the language and lack of embellishment or baggage and especially the lack of a subjective voice, to enable the work to realign with the “what’s next.” If it adapts or not is up to the viewers’ associations and the context. It’s out of my hands once it leaves the studio.

Rail: During the pandemic, I returned to reading Marvel Comics after thirty years, and I’ve decided you are what they call a pre-cog.

Rosen: Pre-con?

Rail: Cog. Precognition.

Rosen: Oh, that’s so funny!

Rail: Over the years you’ve talked to me about how when you start you don’t see things in the work which then others find later.

Rosen: Which is to be expected I guess with language, and encouraged. It becomes richer, or at least different, with usage. I learn a lot from others’ interpretations. I start from a very specific place of discovery or curiosity about language, but I can’t control where it lands.

Rail: There are mutants in Marvel, like some of the X-Men, for example, who are pre-cogs. They each see the future in different ways. Precognition would help explain why your work is able to do what it does.

Rosen: Well, thank you for giving me those powers. [Laughs]

Rail: But this would also mean you’re not really aware of them.

Rosen: I’m not. I don’t think it’s due to anything I do. No powers. More likely it’s what I don’t do, which is not to insert a subjective voice and tell people what to think. I just give them enough rope to hang themselves, as it were. As you know, the work always begins with the language, not with the message. Language and message quickly intersect, but there is a lot of room for people to help shape it.

Rail: You are a particular kind of artist. It’s another superpower you have that your powers of not doing are really very finely tuned. What’s so fantastic about that, and I’m just thinking of this right now, is that even when you do something that could be considered negation, and you probably know where I’m headed, related to the new work….

Rosen: I’m getting a little better at the fine tuning. Economy and efficiency are important to me.

Rail: It’s not negation. There’s really no negativity in your work, even at the work’s most nasty.

Rosen: That’s true. I don’t get on a soapbox, but I do choose my messages, which at least opens the door to negativity.

Rail: The not doing is a productive force or productive procedure in the work overall.

Rosen: I agree. Some of the works don’t require much intervention from me. They are self-made in a “found” sort of way, like Leak (1997), or Sheep In Wolf’s Clothing (1987/2023) for example.

Rail: I wonder if that relates to the earlier work, like from the late 1970s and early 1980s that photographically and systematically document the movements of bodies?

Rosen: I have tried to find the thread that connects them. The still photographic performances for the camera became so numerous (280 photos at one point) that I had to turn to pen and ink notations in the “Stair Walking” series to document the movement, and perhaps those markings led me back to my roots in language, which I had begun working with in 1969 and left for about ten years. Both are strongly based on moving systems. I was more influenced by Steve Reich and Lucinda Childs and their systems of music and dance than by anything in the visual arts. Remember that I didn’t have a background in art.

Rail: I can connect that early work—for example, Double Staircase from 1978—to one of my favorite paintings of yours that will be in the exhibition in Bremen: Still Life from 1993. What connects the now and then of those two works is more tangible and interesting than what makes them different from each other.

Rosen: Really? So how do you see them being connected?

Rail: Is it a still life? Is it not moving? Or is it a still life as in it’s still alive?

Rosen: That is a linguistic connection.

Rail: That’s a painting that is standing still, but it’s also moving. It’s moving in the most provocative ways. It’s in the space between dead and still alive.

Rosen: Maybe it’s being activated by the viewer?

Rail: And not that there’s death in those earlier photographic works, but you didn’t invite an audience to watch people go up and down the stairs, for example. The performative is shifted over into the systematic and the visual.

Rosen: No, they’re definitely still photos. Another connection could be that both Double Staircase and Still Life exist in systems that have set rules which I enjoy because they limit the choices I have to make. I like working within parameters. Both works follow, or break, the rules of the system.

Rail: And that you’ve kept that going in the work—correct me if I’m wrong, but are all the videos you’ve done continuous loops? Is there one that isn’t?

Rosen: Sisyphus (1991/2011) is a loop. Blue Monday (2015) is a loop. There’s one, Between You, Me and the Sea, from 2019 which…

Rail: The US states one?

Rosen: Yes. That doesn’t loop. There is a finale. It’s about the formation of the union through art and typography rather than through chronology and history. It’s funny and suspenseful and a little boring.

Rail: Right. Which makes sense given what that piece is. But mainly when you’ve done video pieces, they are ad infinitum. They loop back.

Rosen: Yes, and the videos are all part of my “Lists” series too. The video loop Blue Monday is a perfect amalgam of two larger systems, days of the week and the colors of the spectrum, but the video loop Sisyphus, actually demonstrates the chaos of the English language with its hundreds of exceptions to the rules. The pronunciation of the name Sisyphus, punctuated by a drum roll and a ta-da, never changes over seventy frames, although the spelling of Sisyphus changes seventy times. It is never spelled correctly.

Rail: Systems is a loaded word for you in different ways. There is also the material and procedural diversity of your work that makes it possible for it to be anywhere in the world, or even, let’s say, in the future on the moon.

Rosen: Well, that’s good. You’re talking about the wall paintings….

Rail: Again, a kind of precognition that maybe you want to develop a practice that can not make itself, but be made by others with the right kind of tools. Hopefully there will still always be professional sign painters.

Rosen: Or vinyl stencils.

Rail: Much of what your work is made of will always be available.

Rosen: I do strive for that. The wall works are conveyable as you mentioned, and one only really needs a skilled sign painter or, if vinyl stencils are used, a skilled team of preparators to execute them, but they can’t be transferred from one situation to another without creating completely new layouts that are resized to the new dimensions and circumstances of the space. So each time, it’s like designing a new installation: new margins, new letter heights and widths, new spacing, even matching colors to available paint via Pantone, RAL, Benjamin Moore, or whatever. In the certificate that accompanies the wall paintings, I try to cover as many what-ifs as possible, but there’s a point where one depends on previous versions providing a guide and then hopes for the best. Whenever I remake a work, I have so many new decisions to make, decisions which someone other than I will have to make someday. I worry.

Rail: I’ll make the bad joke that Kay Rosens can continue to exist as long as we use words.

Rosen: “Can” being the operative word, which doesn’t mean it will. [Laughs]

Rail: On the other hand, another thing I’ve always found fascinating about your work is that it evokes, for example, Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, and Lawrence Weiner, but also On Kawara. It would be beautiful to see a line of your paintings on canvas on a wall across from a line of On Kawara “Date Paintings.” The Painting with a capital P part of Kay Rosen is so crucial.

Rosen: As far as I am aware of, Lawrence Weiner and On Kawara are the two from that group who hand make, or hand paint some of their work.

Rail: I am glad that there are going to be some paintings on canvas in Bremen.

Rosen: Me too. I’m so glad you brought that up, because I love painting and drawing. I could sit at my drafting table for eight hours a day and paint. I should say loved painting because my lungs don’t permit my favorite 1-Shot paint anymore. Many of the large-scale works began small, but they’re sometimes overlooked because the wall paintings are splashier and more attention-grabbing. That said, scale functions like volume and it’s important sometimes to turn up the volume.

Rail: Well I’m of the belief that, for example, however large the wall painting HI from 1997 is going to be in Bremen—and when we did it for the 1998–99 survey at MOCA and Otis it was huge on an exterior wall of the Geffen Contemporary—I could imagine leaving that wall white, hanging Still Life all by itself, and it would look amazing.

Rosen: I think so too. I really like—and it’s hardly ever been done—but the installation of one painting or two on a large wall, I like it so much better than the arrangement of multiple paintings on a wall. Except for my system of hanging multiple small works alphabetically by title along a straight horizontal base line. You don’t have to make subjective decisions. We’re doing that in Bremen.

Rail: True. But another of my favorite works of yours that was also at MOCA and Otis is Corpus from 1992, comprised of thirteen individual paintings that are brought together in a tight arrangement on a wall. The arrangement is a “home” for those paintings, and corpus means body, and you were born and grew up in Corpus Christi, Texas. It is a structure that activates the “what’s next” of the paintings in it.

Rosen: And not only the human body connections, but connections to other bodies, like the heavens: Full Moon and Crescent Moon, expressed partly through the letter form O.

Rail: Yes. Returning again to the what’s next, I know that the museum in Bremen is doing a beautiful book that will be published after they photograph the show. In the press release they use a quote from Kenneth Goldsmith’s text that will be included, which is fantastic. He says that in your work, “words don’t scream for change, rather they quietly enact change, leading by example.” That encapsulates so much of what we’ve been talking about so beautifully and perfectly. He’s not saying you’re leading by example. He’s saying the words and the works lead by example. I appreciate that distinction too. Even though earlier I called you a superhero it’s not like you’re out there wearing a costume and battling all the ways that language can oppress and repress and lie and steal and cheat, and….

Rosen: I love Kenny’s essay. He knows me and the work so well. I am more comfortable behind the scenes letting the language speak for itself rather than consciously speaking through it.

Rail: By leaving it to its own devices, you empower your work to address even those moments when language does awful things.

Rosen: And there are hundreds of decisions to make to get it to that point, but they’re all made with the intention of not so much delivering a message as delivering the potential for a message. But as we said before, I think this all happens because I begin with the language, not with my desire to send a message. For example, in the work I made about climate change, This Means War…! from 2016, I didn’t begin by saying, “I’m going to make a work about global warming.” It began with discovering that the M in WARMING simply adds an extra leg to the N in WARNING, so that the two words can toggle back and forth in the viewers’ mind. By the way, the Weserburg is installing This Means War…! on ten billboards around Bremen in advance of the large UN Climate Change Conference in Dubai from November 30 until December 12. This work has been installed all over the world, so I’m glad that this venue is being added.

Rail: Something that I appreciate about the show in Bremen—and also we should mention the gallery show you had up from September to November at Lora Reynolds Gallery in Austin—is there are works that are dated with two years with a slash between them. You don’t really have any works that have a hyphen in their dates. There’s a break, and then they return.

Rosen: Sometimes many years later. The works in Lora’s show, titled Kay Rosen: FREE FOOD (for thought) are co-dated 1990, 2001, and 2004. Colin Doyle, the director, had a big hand in curating the show and he saw strong connections in the works The Shortest Distance (1999/2023), Pendulum (2003/2023), and Porous (1990/2023) as they represent “now” and “then.”

Rail: In my MOCA catalogue essay “Sounding Out Kay Rosen,” I wrote about stillness and liveliness—that with all the liveliness in the work, it never eradicates the stillness. And I think it’s the stillness waiting for one hundred years from now, one thousand years from now, that it—

Rosen: That’s so poetic, Terry.

Rail: I would say it is fundamentally political. You’re the facilitator of these things. Again, it can be a painting on canvas that of course has a certain shelf life in terms of entropy. I think most art, great art especially, exists within and without time simultaneously. It’s of its time. It’s beyond its time. Your work I think makes this clear in its structural integrity and also—and this is a key word that I know you have used before—playfulness. The playfulness is a big part of it too. The humor, that this isn’t dour, moralizing.

Rosen: Or didactic. Humor is important to me. I don’t intentionally try to make funny work, but I think humor is a product of the “aha” moment or revelation. The delight of discovery. The discovery of a linguistic event that one hadn’t realized before. One problem that arises is when the title is important to the work, like a punchline, but isn’t visible. Recently I gave a talk to an art class at a university in Stockholm and the first question the teacher posed was about the “title problem.”

.Rail: Take a work that is pretty damning, let’s say like, the one about Bush. Is it called “Bush” or “Bullshit”?

Rosen: It’s just called BS (2004). [Laughs]

Rail: BS, right. So the S-H of BUSH and the I-T of SHIT are blocked out. On the left side you see B-U and below it S-H, and then there are four black squares on the right side. So you fill in the blanks and you read bullshit, but then you get … well, I read it more as the second Bush than the first, but they’re both kind of there, I guess.

Rosen: Yeah. I mean, the second one was more dangerous but H.W. Bush certainly did his share of damage.

Rail: BS also points back to a series of paintings on canvas from 1990 that you call “Blocked-Out Paintings” that use black squares and bars to hide some of the letter forms. Their procedure has returned in wall paintings in the Austin and Bremen exhibitions. Let’s start with the Texas wall painting, Porous from 1990/2023.

Rosen: Those 1990 paintings were never done as wall paintings but Colin wanted so much to scale up Porous for the wall because he felt it was so relevant now. The paintings consist of one or two words whose texts are partially blocked out, forcing the reader to create meaning from the hybrid texts and black squares and rectangles. Coracle Press made a small booklet of them too, which included an essay I wrote. The essay is like a piece, because parts of it are blocked out also.

Rail: All the letters of the word POROUS that aren’t the two O’s have been blacked out by two squares and a rectangle.

Rosen: The only meaning that barely squeezes through the six letters is through the O’s and the viewer just has to figure it out. [Laughs] I love these language-meaning intersections where the visual aspects of written language on one hand, and its meaning on the other, seem to exist on a plane beyond vernacular usage. As you know, that’s the reason I turned to art from academia in the 1960s. The things I wanted to explore in language had to be expressed visually. Kenny Goldsmith, to prove my work is literary, tried an experiment in 2010 with one of his graduate students, in which he had her transcribe the book Kay Rosen: AKAK (Regency Art Press) without any visual clues; just typed lowercase letters. No color, no graphic design, no scale, no materials.

Rail: You’ve also updated the blocked out procedure with a brand new work in Bremen that they’re going to produce as a set of wall paintings called Soundtrack (2023).

Rosen: They’re doing it as a wall painting. But I’ve also made it as an edition. It consists of six panels. It is a visually expanding soundtrack that changes throughout the series. The first panel is just three lines of black bars. In each successive panel, more and more letters are revealed. Each one creates its own meaning. But it really isn’t until the last panel where everything is revealed that you get all of the meaning, which isn’t at all what you expect it to be. Should I not give it away?

Rail: Go ahead!

Rosen: Well, by the time this comes out, it’ll be on view.

Rail: People will be posting it on Instagram.

Rosen: Well, okay. The second panel has everything blocked out except DISCO, the top line. The third panel has everything blocked out except DISCO, and V-E-R at the end of the second line. Everything else is still blocked.

Rail: From DISCO to DISCOVER.

Rosen: In the fourth panel, an F-E is revealed at the beginning of the middle line: DISCO FEVER is visible. In the fifth panel DISCO FOREVER can be read. The final panel adds the bottom line: Y-O-N-E. DISCO FOR EVERYONE.

Rail: It took me about thirty seconds to figure out the EVERYONE.

Rosen: I know, because of the Y.

Rail: I was like, I don’t think that’s a word in German!

Rosen: It does make you more self-conscious about extracting meaning.

Rail: What it does is it reinforces something you’ve said from day one. It’s well known that you studied linguistics and you’ve talked about how you became more interested in what you call the unauthorized systems in language rather than the authorized. So the idea that Y-O-N-E is the end of the word EVERYONE but it’s been broken away and becomes nonsense on its own…

Rosen: I sacrificed EVERYONE to FOREVER. You know my old quote: “When it comes to reading my work, throw out all the rules you ever learned: spelling, spacing, capitalization, margins, linear reading, composition … all your old reading habits will be useless.”

Rail: Soundtrack relates to a video like Blue Monday in terms of cadence and rhythm. I don’t know yet how the six panels of Soundtrack are going to be situated in Bremen. But the schematic you sent me presents a work with a beat. You also wrote a short text about the work, about what disco symbolizes for a lot of us, and probably for younger people now as well, is a kind of freedom, liberation, all those good words.

Rosen: My friend David Scott, husband of the late artist Kevin Wolff, wrote a wonderful essay about disco in 2007 titled “Dance Dance Revolution: Disco As Clarion Call To Aspiration.” It feels that way to me.

Rail: Soundtrack is a work entirely from 2023, right? Did you have it in a notebook from years past?

Rosen: No! In fact I had it scribbled on a scrap of paper in the studio, ambivalent about what to do with it, when someone who was making a studio visit happened to see it and loved it. So I gave it to him as a present and took a second look. [Laughs]

Rail: So it really is new.

Rosen: Completely new.

Rail: It demonstrates that the blocked out idea that was manifested in 1990 hasn’t gone away, it continues to be very useful for you in terms of the machinations of your work.

Rosen: Yes. Different strategies for different work. In Soundtrack the process of discovery of a complete and unexpected message in every panel in spite of suppression of information was kind of amazing to me.

Rail: Somehow the work adds up to two hundred percent: one hundred percent censorship, plus one hundred percent added meaning.

Rosen: A surplus of meaning was what Judith Kirshner used to call it.

Rail: It’s not merely that the black bar is censorship, and isn’t everything just fucking awful?

Rosen: Just awful!

Rail: In a way it’s a sophisticated version of those “Unnecessary Censorship” videos on Jimmy Kimmel Live!

Rosen: I never stay up that late.

Rail: They show a clip, bleep things out, but the person wasn’t saying anything that needed to be bleeped, and it makes it so awful or raunchy.

Rosen: Oh that’s great.

Rail: The bleep makes your brain fill it with something.

Rosen: It’s an audio version of the blocked letters.

Rail: In musical scores, black bars can convey rhythm, and a short one can indicate a rest.

Rosen: I like Emma Goldman’s quote too: “If I can’t dance to it, it’s not my revolution.”

Rail: Changing gears, another connection that has popped up in my thinking about your work relates to the work being done by quantum physicists today. For example, I just learned in Carlo Rovelli’s book Helgoland that the brain sends information to the eyes before the eye sends anything to the brain. The brain “predicts” what it is going to see, and the eye only sends information back to the brain if the prediction is wrong. And so I thought, Kay Rosen the pre-cog is even ahead of the curve with this as well!

Rosen: Oh my God, really? I don’t know how the brain predicts without the eyes being the vehicle.

Rail: So maybe your precognition is not like magic or a superpower, it’s just a kind of refinement of what’s really happening on levels that we have no way of perceiving.

Rosen: I gladly doff my cap to the physicists, the philosophers, and the art historians where all of this is concerned.

Rail: Take comfort in your predictive abilities. I also think your grounding in language and your willingness to—I don’t want to say erase yourself, that’s too strong….

Rosen: But it’s true. As I said before, I am more comfortable in a passive role although I have to provide the spark.

Rail: Exactly. And the other thing that’s so great about reading about quantum physics is that it just reinforces how it is really so not about us. [Laughs] My favorite go-to line these days is also from Rovelli, from his book The Order of Time: “A rock is a very slow event.”

Rosen: Sometimes I don’t realize until years later what a work or a body of work is about.

Rail: I do think there’s something about what you keep out of your work. There’s a consistency there. And I’m not just trying to butter you up, I don’t need to let you know how much I’m a fan or how much I love your work.

Rosen: You know the feeling is mutual.

Rail: Just the fact that there could be a kind of consistency without—I mean, there’s no boredom in your work, unless it’s been deliberately planted there somehow in a specific piece.

Rosen: Well, thank you but some might disagree. There is always something discoverable in language, it just has to be recognized.

Rail: It has to be received.

Rosen: Exactly, received.

Rail: It goes back to your beautiful wall painting The Forest for the Trees from 1990, in which the letters from “for the trees” are added to the phrase “the forest.” That piece will also always play with the cliched idea of the question, if a tree falls in the forest does it make a sound?

Rosen: The sound was in my head I guess. I remember I was on the subway and I guess I was starved for greenery and realized that “the forest” and “for the trees” had the same letters, so you could spell “the forest” using all of the excess letters: tthhee ffoorrreeesstt. You couldn’t see/read “the forest” for “for the trees.” This is an example of the place where I begin not necessarily being the place where the work lands.

Rail: It reminds me of Wittgenstein’s duck/rabbit drawing that captured Jasper Johns’s attention. Some people can only see the duck, some only the rabbit, some people are capable of really seeing both all at once. And so it becomes this weird thing, that it can be a duckrabbit.

Rosen: You can’t see the duck for the rabbit, and so on. [Laughs]

Rail: I keep thinking of your greatest hits. You know how much I love that painting of yours called Tricknees from 1993. I’m obsessed that the two K’s in the center don’t need to be in the pronunciation of the words trick and knees, but then they become two pairs of legs, each of which has one trick knee.

Rosen: That goes back to letter forms. That was part of the same group of paintings on canvas as Still Life that actually displays the phrase FRUiT DiSH. Where something in the letter forms dovetails with the meaning, like the dots over the i’s in the phrase that become cherries on top. But it goes to composition. If the K’s weren’t isolated on the middle line between TRIC and NEES, the point wouldn’t be made.

Rail: Of course you were blessed with a name that can be represented by a single letter, K. I’ve always said every time there’s a K in a Rosen work, she’s there—that’s her.

Rosen: [Laughs] There is also the work called Also Known As Kay from 1992 that is also one of the thirteen paintings that are a part of Corpus: AKAK.

Rail: Yes! And I thought you drove the brilliant point home in that great work on paper called Self-Portrait (1998/2018) where you write the phrase “If You See Kay” and when you say it out loud you realize you are also spelling the word “fuck.”

Rosen: I know. It’s perfect, isn’t it?