For decades — even a century or more — public art in Boston has been easy to define: By material (granite, marble, bronze), by format (human figures, usually on horseback, usually male) and by theme (historic, historic, and historic; the older the better).

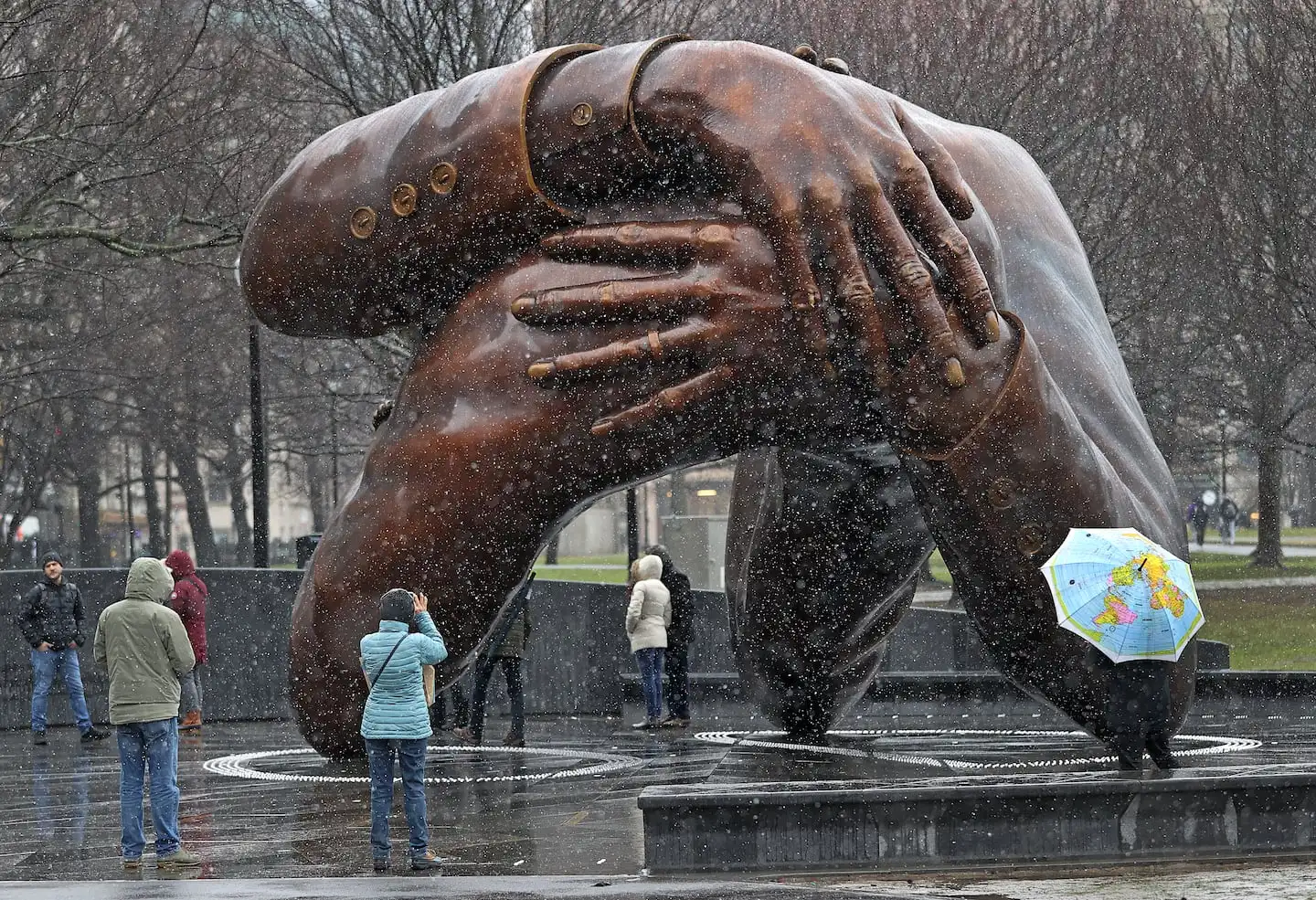

But in recent years — slowly, sometimes painfully — a new vision of Boston has begun to emerge. That was never more clear than in late 2022, when “The Embrace,” Hank Willis Thomas‘sconfounding, colossal tangle of hands and arms arrived on Boston Common. A memorial to Martin Luther Jr. and Coretta Scott King, it loudly proclaimed a shift that had labored to express itself in whispers.

While Boston has surely lagged its urban peers as it stood pat on an old vision of itself, it’s about to make up for lost time: Next month, the Boston Public Art Triennial will arrive with two dozen new works displayed downtown and across the city, in neighborhoods from Charlestown to Mattapan. Partnered with the city’s venerable art museums as well as the city itself, the Triennial’s ambitions fit with a city refashioning a new sense of self.

“It really does feel like a completely different city than 10 years ago,” said Kate Gilbert, the Triennial’s executive director. “There’s just a greater aptitude for experimentation. We’re over our fear of the ephemeral — of a lot of those old fears, I think.”

Specifics will be made public next month, but installations will run a gamut of form and idea, from large-scale sculpture to video to performances, by artists both local and far-flung: Boston’s Alison Croney Moses and Stephen Hamilton, Nicholas Galanin, a widely celebrated Indigenous artist from Alaska.

For Hamilton, whose project will be installed in Roxbury, the Triennial “is not something I could have imagined when I graduated (from MassArt) in 2009,” he said. “But I’m also looking to the future. How can an event like this help us grow?”

He might look to the rare feat of cooperation the Triennial has achieved: the Museum of Fine Arts, the Institute of Contemporary Art, and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum are all taking part and the city will contribute its own slate of projects, too.

“The idea, really, is to have an experiment happening out in public,” said Karin Goodfellow, the city’s director of transformative art and monuments. “We’re testing civic space in different ways, and trying to find different pathways to release some assumptions and find ways to approach what we do that feels authentic and organic to the city’s cultures.”

Boston’s reputation as an international cultural center is rooted in its past, and its public art landscape reflects that: George Washington on horseback in the Public Garden; Paul Revereat the North End Church. Making inroads to set-in-stone narratives isn’t easy, but Gilbert knows the terrain. In 2015, she founded the Triennial’s precursor, Now + There, a nonprofit with a mission of promoting contemporary public art.

Now + There’s projects were everything Boston’s public realm was not: Ephemeral. Contemporary. Oblique. Diverse. Some works were predicated on play; others, live flower gardens. Projects were often made for neighborhoods the city’s gilded cultural reputation rarely touched: Roxbury, Chinatown, Dorchester, Grove Hall — a priority to which the Triennial has remained faithful.

The Triennial will re-up its citywide program every three years, and its aim is not modest: To be a permanent emblem of a new Boston that’s waited so long for its time to come. Partnerships are key to that vision. At the MFA, the museum’s contribution to the Triennial effort flanks its grand entrance: A pair of shimmering chromium sculptures by the Mohawk artist Alan Michelsoncalled “The Knowledge Keepers.” They depict Julia Marden and Andre StrongBearHeart Gaines Jr., living Indigenous people with expertise in their cultures’ history.

The museum’s contribution to a new way of seeing an old city, “The Knowledge Keepers” is heavy with symbolism of a city in the throes of change. A tacit response to “Appeal to the Great Spirit,” Cyrus Dallin’s 1909 bronze sculpture of an Indigenous man on horseback, arms spread wide. The contrast is not subtle: Dallin’s piece, a forlorn Native American now often seen as a cliched pastiche, has sat on the front lawn of the museum since 1912; it’s a bleak relic next to Michelson’s vibrant representation of contemporary people, living their lives in the now.

Meeting with Triennial staff over time, “it’s been clear to me that they were always approaching us with this idea that (the Triennial) could be a real change agent in the way in which Bostonians think about the art that’s around them in the city,” said Ian Alteveer, chair of the MFA’s Contemporary Art Department, who commissioned the work. “I’m thrilled, and I’m also learning from this process myself.”

At the City of Boston, Goodfellow is stewarding the city’s own attempt at ephemeral, experimental public culture as part of the Monuments Project, funded with a $3 million grant from the Mellon Foundation.

The program distributed $1 million of that grant among five local curatorial partners, the Triennial included. The city also has a roster of its own projects, to be announced later this month. Called “Un-monument,” its aim is to counterweigh Boston’s traditional civic narrative with projects that elevate long-overlooked episodes and people.

Though it may feel sudden, new ways of thinking about public space — who it’s for, what it can say, what it can do — are the product of a long, slow evolution. Unease around monuments in particular as simplistic emblems of complex histories had been simmering for years when, in 2020, the murder of George Floyd brought sudden, urgent action.

In Richmond, Va., a bronze statue of Robert E. Lee astride a horse became the hub of a nationwide takedown movement. Installed in 1890 to give symbolic form to the racist policies of the Jim Crow South, the Lee statue was removed in 2021.

Boston’s history is less fractious than the segregated South, but the urgency of the moment brought its painful racial divides to the surface. Its clearest manifestation was an effort to remove Thomas Ball’s “The Emancipation Group,” a 19th-century bronze in Park Square of Abraham Lincoln anointing freedom upon the enslaved Black man crouched before him. A thousands-strong petition led by artist Tory Bullock prompted the city’s Boston Art Commission to vote unanimously to remove it in June 2020.

That same month in the North End, vandals beheaded a marble statute of Christopher Columbus, beloved in the Italian community but reviled by many as a symbol of European colonization.The statue was removed a few days later. Months later, on Indigenous People’s Day (the former Columbus Day), a blank, human-shaped figure took its place on the empty stone plinth. Installed by Boston artist Cedric Douglas, he projected the images of an array of local icons as a public honor: Elma Lewis, the iconic Roxbury arts educator; Mel King, the long-time Civil Rights activist; Jessie “Little Doe” Baird, a Native American linguist who helped preserve and revive the Wampanoag language.

He called it “The People’s Memorial Project,” and Goodfellow could see its potential. As part of the city’s Unmonument efforts this summer, Douglas will extend the project he began in 2020; he’ll be out in public asking Bostonians what should occupy the empty plinth where “The Emancipation Project” stood. “These are the kinds of projects that we mean to inform us going forward,” Goodfellow said.

Public experiments are the lifeblood of a necessarily nimble outfit like the Triennial. For a city government and art museums, it’s new terrain. But they’re learning from each other in a way that could help rewire how the city itself thinks about public art.

“We can offer them some thoughts on the public realm that they haven’t really engaged with, and we’re learning from them, too,” Gilbert said. “But it’s about trust and collaboration more broadly, and that’s what’s really exciting.”

And maybe, just maybe, this experiment waiting to happen can help show Boston not what it’s always been, but what it could be, she said. “It feels like a Pollyanna moment,” she laughs, “but “If we can do this at the civic level, really, what else can we achieve?”

Murray Whyte can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him @TheMurrayWhyte.