Abstract

Modern morphometric-based approaches provide valuable metrics to quantify and understand macroevolutionary and macroecological patterns and processes. Here we describe TriloMorph, an openly accessible database for morpho-geometric information of trilobites, together with a landmark acquisition protocol. In addition to morphological traits, the database contains contextual data on chronostratigraphic age, geographic location, taxonomic information and lithology of landmarked specimens. In this first version, the dataset has broad taxonomic and temporal coverage and comprises more than 55% of all trilobite genera and 85% of families recorded in the Paleobiology Database through the Devonian. We provide a release of geometric morphometric data of 277 specimens linked to published references. Additionally, we established a Github repository for constant input of morphometric data by multiple contributors and present R functions that help with data retrieval and analysis. This is the first attempt of an online, dynamic and collaborative morphometric repository. By bringing this information into a single open database we enhance the possibility of performing global palaeobiological research, providing a major complement to current occurrence-based databases.

Background & Summary

Understanding biotic responses to large scale environmental changes -either past or recent- is one of the main goals of macroecology and macroevolution. Major biological events that took place during the Palaeozoic, such as the Cambrian Explosion, the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event (GOBE), and the mid-Palaeozoic Marine Revolution, shaped the marine life for the rest of the Phanerozoic and paved the way for the forthcoming configuration of current marine ecosystems1,2,3,4. Among the iconic organisms of this Era, trilobites are a fundamental group for the study of Palaeozoic benthic faunas and provide excellent opportunities for the understanding of mechanisms underlying ecological and evolutionary patterns at different spatial and temporal scales5,6,7,8,9. Several palaeontological studies have highlighted the critical role of trilobites in the signature of the Cambrian–Ordovician ecosystems and, although declined significantly during the Late Ordovician extinction, they continued being an emblematic group of the benthic ecosystems during the middle Palaeozoic10.

Palaeobiodiversity studies have classically examined taxonomic changes on the basis of the fossil record11,12,13,14,15. Indeed, understanding the patterns of diversity collapses and recoveries provides valuable insights into drivers of changes and helps to inform conservation activities in modern marine ecosystems in light of anthropogenic climate change16,17. Most of these studies are facilitated by the Paleobiology Database18 (PBDB) or the Geobiodiversity Database19 (GBDB), which are comprehensive, international collaborative, taxonomic and occurrence databases already available and widely used to assess macroevolutionary patterns and processes in deep time and for global to regional analyses20,21,22,23,24. Related studies, therefore, focused mainly on the taxonomic richness component of biodiversity. However, it is well-known that biological diversity is multifaceted (e.g.25), and morphological diversity is another key aspect to understanding ecological-evolutionary patterns in deep time26.

For extinct organisms such as trilobites, morphological disparity is highly relevant to understand and quantify macroevolutionary and macroecological patterns and processes (e.g.5,27,28,29,30). Modern morphometric-based approaches, such as landmarks and morphospaces, are also used as valuable metrics to quantify impacts and responses of marine ecosystems to large-scale changes (such as global warming) in terms of morphology and functional needs through deep time (e.g.31,32,33,34,35,36,37). Regarding morphological information, only small datasets linked to specific publications exist, while very few large scale morphological datasets are currently available (e.g.38,39,40). Regarding trilobites, there has been an increase in taxonomically comprehensive morphological databases41, such as outline data describing the shape of the cranidium31, semilandmarks describing the shape of the cephalon42, landmark and semilandmarks configuration on cephalic outline, glabellar and eye ridges43, landmarks and semilandmark data on cephala and pygidia44, as well as trilobite moult morphometric measurements45. Here, we develop a database for morphological information of trilobites that is also quantified by means of geometric morphometrics state-of-the-art methods. These approaches allow objective quantification of shape of organisms, ordinate major shape differences onto morphological spaces, and then quantify the occupation of this morphospace by various disparity metrics and compare them to phylogenetic patterns or known abiotic and biotic changes. The novelty behind TriloMorph is its dynamic and collaborative nature, thus promoting inclusive and sustainable work between researchers, approaching an open science framework.

Trilobites are extinct marine mostly benthic, mobile organisms forming the class Trilobita, one of the earliest known groups of arthropods. They first appear in the fossil record around 521 Ma ago and flourished throughout the lower Palaeozoic46,47, before slipping into a long decline, with all trilobite orders except the Proetida dying out during the Late Devonian48. The last trilobites finally disappeared at the end-Permian mass extinction about 252 Ma ago49. Trilobites were among the most successful of all early animals, thriving in oceans for almost 270 million years, with over 20,000 species having been described41,50. Due to their excellent fossil record and high diversity and abundance, they are an ideal group for analysing biotic changes during the Palaeozoic.

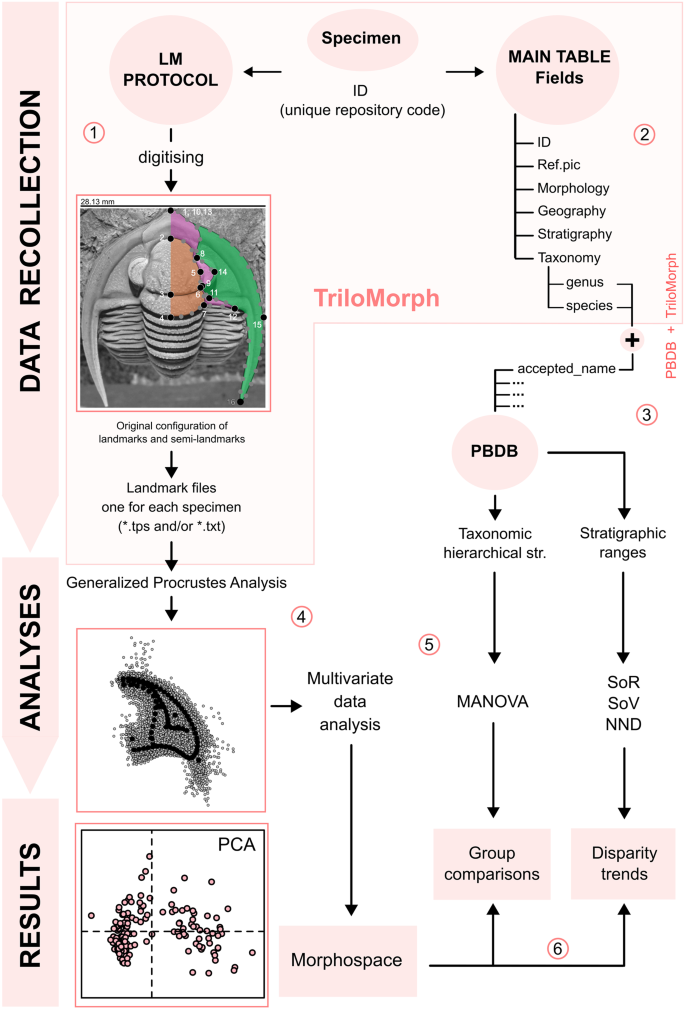

In this first release of the openly accessible “TriloMorph” Database, we describe the general landmarking protocol and database functionality (Fig. 1). The initial dataset is focused on Devonian trilobites, and late Cambrian–Early Ordovician ones to a lesser extent, which have a very rich fossil record at times where major transitions of life happened10,51. The morphology of most Devonian trilobite genera with records in the PBDB has been digitized and compiled in the database which, in addition to these morphological traits, contains contextual data on chronostratigraphic age, geographic location, taxonomic information, and lithology of the landmarked specimens. TriloMorph is the first attempt of such an open online morphometric repository of extinct marine organisms that promotes and brings together data generated from the collaborative efforts of contributors in a dynamic manner. The possibility of integrating morphometric data with data from the established Paleobiology Database, which is the biggest online resource of fossil occurrence data, provides the opportunity to address large-scale palaeobiological studies.

Flow diagram illustrating the main TriloMorph workflow: (1) LM protocol: the acquisition of morphological data of a specimen with unique repository code (ID) is carried out following the provided landmark protocol; after digitising, one landmark file is generated for each specimen. (2) Main table: specimen ID conforms the basic unit of entry in the main table that contains specimen-level traits and contextual characteristics (‘data.csv’). (3) PBDB + TriloMorph: taxonomic hierarchical structure and stratigraphic ranges can be obtained by merging TriloMorph data with occurrence and higher taxonomic information from the PBDB by using the accepted name from PBDB and species or genus names from TriloMorph, (4) Generalised Procrustes analysis: standardisation of landmark data. (5) Analyses: a variety of analytical tools can be used to quantify shape variation (e.g. multivariate data analysis, MANOVA, disparity measures) depending on the research goal. (6) Results: with this database and protocol it is possible to construct a morphospace to visualise patterns of shape variation in trilobites, carry out group comparative analyses or study disparity trends. A step by step explanation of the procedure and R function utilisation is given for the highlighted part (pink box) and an example on the analysis and results sections using Devonian genera from TriloMorph is provided in the R code TriloMorph-workflow. Abbreviations: LM: landmark; Taxonomic Hierarchical str.: Taxonomic Hierarchical structure; SoR: sum of ranges; SoV: sum of variances; NND: Nearest neighbour distance; PCA: principal component analysis.

Methods

Morphological data were compiled from a landmark-based geometric morphometric approach52 to investigate the morphology of two major anatomical structures of trilobites, namely the cephalon and the pygidium. Specimens selected for digitization were compiled from the literature and belong to public collections with a unique repository code. Specimens were named after this alphanumeric identifier and digitised from their original 2D published pictures (Fig. 1, Data recollection). In this sense, 2D landmark configuration has proven to be adequate for capturing shape change in trilobites, despite the differences that may exist in the convexity of certain structures53. Landmarks and semilandmark curves were referred to the right half of the structures analysed, on a dorsal view of each specimen. If a specimen had the left side better preserved, the picture was mirrored prior to landmarking. When missing, a graphic scale was placed on each specimen prior to digitization. Morphology of the cephalon is described by 16 landmarks and 4 semilandmark curves, and the pygidium by 7 landmarks and 3 semilandmark curves (Tables 1, 2, Fig. 2). Geometric morphometrics enables describing the shape of organisms by specifying landmarks, which are homologous topological points identifiable in all studied specimens, as well as semilandmarks, which are equally-spaced points capturing the shape of boundary curves and of surfaces54. Semilandmark curves for the cephala represent the shape of the glabella, cranidial and cephalic outlines and the posterior part of the cephalon (Figs. 2, 3). Regarding the pygidium, the semilandmark curves represent the pygidial and axis outlines and the border furrow.

Template of landmarks and semilandmarks curves used in the TriloMorph database illustrated on three different genera (Cyphoproetus, Harpes, and Kayserops, from the left to the right). For Harpes, absent landmarks are referred to as crosses besides the figure. Figures adapted from Gon, S.M. III114, used with permission.

Schematic diagram of the cephalon of Ellipsocephalus, showing the alternative position of LM 15 in the template used in the geometric morphometric analysis. Figure adapted from Gon, S.M. III114, used with permission.

Landmark quantification may vary between specimens depending either on the preservation of the specimen or because the specific trait is not present in the respective taxon; for example eyes in blind taxa or specimens with no articulated cephala. In the case of an incomplete specimen selected for digitization, for example, a cephalon with a broken genal spine, we completed its morphology by taking in reference another specimen from the same publication. In exceptional cases where certain taxa do not have well preserved structures, drawings were used for digitization if they were based on a specific specimen with a repository code. However, it is frequent that some taxa lack certain structures; in these cases, we suggest removing these traits from the analysis. In the static release, 82% of the specimens in the database allow complete landmark acquisition in the cephala and 100% in the pygidia. Also, this first release includes only adults (early holaspid and holaspid) specimens.

Landmark and semilandmark selection will ultimately depend on the scope of the analysis. Thereby, here we present a comprehensive digitization protocol.

Several softwares exist for 2D landmark acquisition, such as ‘ImageJ’55, ‘tps’ series56, or the digitize2d() function in the ‘geomorph’ R package57,58. Here, we used both the ‘digitizeImages()’ function in the ‘StereoMorph’ package59 for R60, and the classical ‘tpsDig’ software56.

Data Records

Here we provide the release of a geometric morphometric dataset of 277 specimens. The associated metadata has information down to specimen level, thus allowing, for example, to include several specimens of the same species for intra-specific analyses. Because it is a specimen-based dataset, TriloMorph allows users to carry out analyses at any desired taxonomic resolution. All specimens included in this release are linked to published references (i.e. peer-reviewed papers, taxonomic monographs, books etc., see references in the GitHub repository) and are derived from localities all around the world (Fig. 4). As a first step, and as a strategy to maximise taxonomic coverage of the dataset, we include one specimen per genus. The current version of the dataset has broad taxonomic and temporal coverage and comprises more than 55% of all trilobite genera and 85% of families in the PBDB in the Devonian geological stages (Fig. 5) and even some taxa yet lacking occurrences in the PBDB. Static releases of the database are available directly from the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba data repository61 and Zenodo62, while a dynamic collaborative version is available in GitHub (https://github.com/balsedie/trilomorph). The purpose of the TriloMorph GitHub repository is to allow the constant input of new data into the database. We also provide a step by step explanation of the procedure to upload new data and describe the R functions needed to download and analyse data hosted in this repository. Static releases are in the form of a compressed folder containing the following files and folders:

Palaeogeographic map of the Eifelian Stage (Middle Devonian) indicating the geographic location of the studied collections of trilobite specimens included in the TriloMorph database (green) and location of collections from the PBDB (pink) in order to show the geographic coverage of TriloMorph. Palaeogeography is reconstructed using the PALEOMAP model115 in GPlates116.

Amount of genera documented in the TriloMorph database (green) in relation to the number of trilobite genera for each Devonian stage recorded in the PBDB (yellow). Taxonomic richness was range standardised based on the Devonian occurrences recorded in the PBDB.

Metadata

YAML file containing the contextual information of considered specimens (see below and Table 3). YAML is a human-friendly data serialisation language for all programming languages63.

References.csv

A CSV-formatted file containing the bibliographic information of data sources. Each entry of the specimen-based table (‘data.csv’) contains the identification number of the data source, whose bibliographic details are provided in this ‘reference.csv’ table, which can then be used for citation purposes and should be credited in subsequent publications using the database. Contributors are also acknowledged in the accompanying file ‘contributors.csv’.

Images

A folder containing the digitised images. Image files are named after the specimen identification number (i.e., collection/repository number, also present in the main table ‘data.csv’), and are appended with a suffix to identify the corresponding anatomic structure of the trilobite (“_C” and “_P” for the cephalon and the pygidium, respectively). File names should not contain spaces. All pictures have a graphical scale. Available formats are JPG and PNG. Images of cephala and pygidia are saved in different subfolders.

Landmarks

A folder containing the shape data (landmarks and semilandmark curves) for each specimen separately. Similarly to images, landmark files are named after the repository code of the corresponding specimen appended with the suffix of the considered morphological structure (see above). Shape files created with StereoMorph (*.txt) or tpsDig (*.tps) are available. Shape files of cephala and pygidia are saved in different subfolders.

The database is, therefore, a collection of data files overseen by a main table designed to contain specimen-level traits for considered taxa. The basic unit of entry in this main table is that of a specimen, normally stored in public collections and with a unique alphanumeric identifier (id), that is also accompanied by contextual characteristics such as the publication describing this specimen (ref.pic), taxonomic information (taxonomy.genus, taxonomy.orig_genus, taxonomy.gen_status, taxonomy.gen_author, taxonomy.subgen, taxonomy.sp, taxonomy.orig_sp, taxonomy.sp_author, taxonomy.subsp), relevant morphological information (morphology.cephalon, morphology.cranidium, morphology.pygidium, morphology.eyes, morphology.ontogeny), geographic context (geography.lat, geography.long, geography.country, geography.state, geography.county), and stratigraphic information (stratigraphy.formation, stratigraphy.min_age, stratigraphy.max_age, stratigraphy.ref_age, stratigraphy.basin, stratigraphy.environment). These metadata are crucial for subsequent analyses of morphological disparity in a spatial, temporal and environmental context. Details about each field are described in Table 3. Although it is not the current scope of the database, the specimen-based structure of the database allows including several specimens of the same species to also perform intraspecific analyses.

In addition to the database, we also provide several R functions to read both StereoMorph and TPS data simultaneously (function ‘shapRead’ in the file ‘trilomorph-funs.R’) into a list structure, then to check homogeneity (number of landmarks, number of curves and constituting semilandmarks, presence of a scale, presence of missing landmarks) of the loaded landmark data, next to resample each curve to the same number of semilandmarks as requested by the user (function ‘shapFix’ in the file ‘trilomorph-funs.R’) and to finally provide a standard 3D landmark array (landmark values by landmark dimension and by specimen, see64). In case of inconsistencies among the selected specimens, the latter function automatically removes these specimens with missing landmarks.

Technical Validation

The acquisition of landmarks for this database used softwares, such as tps56 and StereoMorph59, which have been abundantly used in palaeontology and biology for decades and have proven to be efficient and accurate, therefore, ensuring technical rigour (e.g.52,64).

The landmark template defined here is the result of a collaborative work among many trilobite specialists in our group (e.g44,48,51,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86) and is also based on a long historical research of landmark-based protocols in trilobites (e.g42,84,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95). It is designed to maximise trilobite shape description across all major trilobite orders.

One important concern might be the capability of the proposed landmarking protocol to recognize trilobite morphological variation across its whole -or at least most of the- phylogeny but also recognize variability within taxonomic groups. In this sense, our results of the trilobite morphospace indicates that the current protocol is particularly sensitive to the main morphological changes that have been previously described in the literature96,97 (Fig. 6). For example, our method is able to capture the cephalon outline, but also suture and glabellar outline and eye morphology, as well as key pygidial features, all of which have been interpreted as important traits when describing the morphological variability among trilobites97. Results using this protocol demonstrated its ability to distinguish main morphological variations across all orders and families present during the Devonian (see Usage notes), as well as at regional and local scales during the lower Ordovician77, and within a single family (Phacopidae) along its whole evolutionary history44.

Trilobite morphospace using Devonian data from TriloMorph, virtual shapes are plotted in order to show intuitively how shape varies across morphospace. Note that our landmarking protocol is particularly sensitive to the main morphological changes described in the literature96. For example, the lower right quadrant represents mostly morphological diversity among Phacopidae, towards the upper part mostly Homalonotidae, Styginidae, Calmonidae, towards the lower left quadrant morphological diversity resembles Acastidae, Odontopleuridae, Aulacopleuridae, Proetidae.

However, there are some taxonomic groups that represent a challenge for the application of this protocol. For example, in several trilobite clades (e.g. some representatives of the Suborder Illaenina, and the Order Asaphida) effacement of cephalic and pygidial furrows is a common feature, making it difficult to determine certain landmarks and curves. On the other hand, there are several types of facial sutures, and therefore the curves and landmarks involved have been resolved to encompass these different patterns. For instance, for marginal sutures that run along the cephalic margins, LM 10 (anterior facial suture at the sagittal line) is placed together with LM 1 and so the cranidial outline is adjacent to the cephalic margin (e.g. harpetids); for sutures running parallel to the anterior border, LM 10 is positioned between LM1 and LM2 so the anterior part of the cranidial outline runs parallel to the margin (e.g. dalmanitids) (Fig. 2).

Because the database is based on landmarked data obtained by different contributors and digitising software, we tested for variation on landmarked data as a measurement of data quality. We tested three different sources of error for morphogeometric data, namely within and between observer variability in the landmarking process, and variability between different landmark acquisition software. For this, we compared inter-generic variability in our dataset with variability in a single specimen based on (1) ten landmark and semilandmark configurations obtained by the same observer (within observer variability, two test cases) and (2) landmark and semilandmark configurations obtained by 8 different observers using StereoMorph and one observer using TPS (among observer variability). Morphological variability was estimated as (1) the pairwise Procrustes distances among specimens within each group: among-genus, among-observers and within-observers and (2) total multivariate dispersion in the morphospace for each group. Results indicate that within observer variability, i.e. strict measurement error (0.014 and 0.02), and among observer variability (0.028), which in turn includes different landmark acquisition software variability, are substantially smaller (one order of magnitude) than inter-generic variation (0.35), see Fig. 7.

Morphological variability among specimens from two sources of error for morphogeometric data: within-observer (within-obs. 1, within-obs. 2), and among-observers (among-obs,), compared to among-genus variability. (a) Distribution of pairwise Procrustes distances among specimens within each group. (b) Morphospace for measurement error for specimens within each group.

A Kruskal-Wallis rank test confirms that the differences in pairwise Procrustes distances are statistically significant (χ² = 349.85, df = 3, p < 2.2e-16). The test for multivariate dispersion98 also indicates statistically significant differences (df = 3, F = 80.524, p < 2.2e-16). We further used a Tukey test to recognise which groups were significantly different based on their multivariate dispersions. Table 4 indicates that significant differences are present only when comparing inter-generic variability to among-observers and within-observer variabilities (within-obs.1 and within-obs.2). While among observer variability is higher than personal error, it is still non-significant (Table 4). It is worth mentioning that measurement error tests using TPS were carried out in a previous study (see supplementary material in44), which also indicated a negligible variation compared to inter – genus variation.

In a second analysis, to further assess the robustness of morphometric quantification, we tested variation on landmark data by intentionally misplacing a landmark. For this, LM 15 was slightly moved from its original position by one of the observers. Among-observers variability was tested considering both landmark and semilandmark configuration and only landmarks (excluding semilandmark curves). The former, increased as expected (0.032), although it remains non-significant with respect to inter-generic variation. However, variability considering only landmark configuration was higher (0.041), highlighting the importance of the location of landmarks that make up for the ending points of semilandmark curves (Fig. 8). Thus special consideration must be taken in the positioning of these landmarks.

Morphological variability among specimens considering among-genus and among-observers sources of error. Note the increase in morphological variability among-observers when slightly changing the location of a landmark that makes up for the ending point of a semilandmark curve (orange shade). Abbreviations: config.: configuration, LM: landmarks; obs.: observer, var.: variability.

These results indicate that at the current scale of the dataset, sources of error in the morphogeometric data are much smaller than the natural variability of the data. Therefore our protocol for obtaining data digitised by different contributors is reliable for large scale analyses. Our results are further supported by previous analysis using the same landmarking protocol48 where measurement error was lower than within species variability and significantly lower than among genera variability for a single morphologically conservative family (i.e. Phacopidae)44.

Finally, part of the database has already been used to investigate trends of morphological disparity of a specific group of Devonian trilobites44 and ecological dynamics of late Cambrian–early Ordovician trilobite assemblages77, therefore showing the applicability of our database and the usage notes discussed below.

The database is hosted on github62 and will be maintained on the long-term by DB, FS and other members of the database.

Usage Notes

A database for morphological information of trilobites is presented herein. The database is open-access with the possibility to download information of interest and/or contribute to the dataset. Researchers who use the database are asked to cite this publication; we strongly encourage users to acknowledge main contributors to the analysed dataset. This novel database is ideal for quantitative analyses regarding morphological diversity, providing an excellent opportunity to explore macroevolutionary and macroecological dynamics.

Nowadays, geometric morphometric analyses are routinely used and there exist several softwares with various capabilities and options to perform such analyses (e.g. MorphoJ99, Morpheus100, PAST101), as well as several packages (e.g. geomorph54, shapes102, Momocs103) for R60. As an example, here we show the potential of the database for analysing morphological disparity through time, focusing on the Devonian. For this we follow a classical protocol schematized in Fig. 1 (the corresponding R code is available in the file ‘trilomorph-workflow.R’ provided with the TriloMorph database):

1. Load and match landmark data to the user-specified template, number of landmarks, and number of semilandmarks for each open curve (e.g. with the function provided with the TriloMorph database). The number of semilandmarks to be placed along the curves will ultimately depend on the user’s desired resolution of the shape data. In this contribution we resampled the 4 curves on the cephalon to 12, 20, 20 and 20 semilandmarks respectively because it was sufficient to fit our scope. Here, we use shape files created with StereoMorph (*.txt) or tpsDig (*.tps), but any other format can be used as long as it can be transformed into the standard array (‘landmark values by dimension by specimen’; see64). The function shapFix can be used to easily change the desired number of semilandmarks for each curve as an argument, and also will warn the user and automatically remove specimens with landmark data not fitting the desired template in order to continue with the general analysis.

2. Landmark data are standardised (superimposition step) by applying a generalised Procrustes analysis (GPA; e.g. the function ‘gpagen’ in the geomorph package), which facilitates the comparison of configurations by eliminating variation associated with differences in their location, orientation and size52,104,105,106,107.

3. Superimposed data are ordinated into a morphological space by applying a covariance-based principal component analysis (PCA; e.g. the function ‘plotTangentSpace’ in the geomorph package) in order to quantify and visualise patterns of shape variation. Actual shapes and/or virtual shapes can be plotted over this morphospace to illustrate and highlight major shape variations (Fig. 6).

4. Last, to quantify the morphospace occupation and its changes through time, we calculated the sum of variances (SoV; Fig. 9), which provides a measure of dispersion around the centroid of the group. Noteworthy, several other disparity indices have been developed to capture different aspects of morphospace occupation, and thus consideration of multiple indices is necessary to fully characterise changes in disparity108,109,110. These additional indices can be computed with the dispRity package111. In addition, taxonomic richness was standardised according to the Devonian occurrence records from the PBDB.

Devonian disparity and diversity trends based on TriloMorph morphometric data (measured as the SoV) and on trilobite genera present in the PBDB and in TriloMorph respectively.

In our example, the Devonian data from TriloMorph combined with the PBDB shows correspondence between taxonomic and morphological diversity during the Lower and Middle Devonian, where the highest disparity values are related to moments of high taxonomic diversity (Fig. 9). However, towards the Eifelian–Givetian diversity decreases significantly in relation to disparity, with a clear decoupling during the Frasnian. These trends rule out random extinctions as disparity does not remain stable, rather it slowly decreases towards the Upper Devonian. This, in relation to morphospace occupation patterns (Fig. 10), suggest selective extinctions towards the margin, characterised by moderate reductions of the SoV paired with asymmetric reductions of datapoints112.

Morphospace for Lochkovian – Famennian trilobites using data from TriloMorph. Accentuated data points indicate morphotypes present in the respective intervals, morphotypes that are absent (x) are also indicated in order to show the total spectrum.

For large scale analyses, the dataset is meant to be used in conjunction with occurrence data (obtained from the PBDB for example). Indeed, morphological information from TriloMorph and occurrence and higher taxonomic information from the PBDB can be merged according to the desired taxonomic resolution using the genus or species names (Fig. 1: Data recollection). The ‘TriloMorph-workflow’ R script associated with the database illustrates in detail how to merge together occurrence data (such as from the PBDB) to the TriloMorph geometric data and to analyse them to produce disparity curves for example (see Figs. 4, 5, 9, 10).

Code availability

The R script and functions written by the authors used in the analysis are available at the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/balsedie/trilomorph. Analyses have been computed with R version 4.1.3113 with specific functions (available at Github) and the package geomorph version 4.0.157,58.

References

-

Signor, P. W. & Brett, C. E. The mid-Paleozoic precursor to the Mesozoic marine revolution. Paleobiology 10, 229–245 (1984).

Google Scholar

-

Klug, C. et al. The Devonian nekton revolution: Devonian nekton revolution. Lethaia 43, 465–477 (2010).

Google Scholar

-

Harper, D. A. T., Zhan, R.-B. & Jin, J. The Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event: Reviewing two decades of research on diversity’s big bang illustrated by mainly brachiopod data. Palaeoworld 24, 75–85 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Servais, T. et al. The onset of the ‘Ordovician Plankton Revolution’ in the late Cambrian. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 458, 12–28 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Foote, M. Morphologic patterns of diversification: examples from trilobites. Palaeontology 34, 461–485 (1991).

-

Adrain, J. M., Westrop, S. R., Chatterton, B. D. E. & Ramsköld, L. Silurian trilobite alpha diversity and the end-Ordovician mass extinction. Paleobiology 26, 625–646 (2000).

Google Scholar

-

Peters, S. E. Relative abundance of Sepkoski’s evolutionary faunas in Cambrian–Ordovician deep subtidal environments in North America. Paleobiology 30, 543–560 (2004).

Google Scholar

-

Waisfeld, B. G. & Balseiro, D. Decoupling of local and regional dominance in trilobite assemblages from northwestern Argentina: new insights into Cambro-Ordovician ecological changes. Lethaia 49, 379–392 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Saleh, F. et al. Contrasting Early Ordovician assembly patterns highlight the complex initial stages of the Ordovician Radiation. Sci. Rep. 12, 3852 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Adrain, J. M., Fortey, R. A. & Westrop, S. R. Post-Cambrian Trilobite Diversity and Evolutionary Faunas. Science 280, 1922–1925 (1998).

Google Scholar

-

Sepkoski, J. J. A Factor Analytic Description of the Phanerozoic Marine Fossil Record. Paleobiology 7, 36–53 (1981).

Google Scholar

-

Sepkoski, J. J. Biodiversity: Past, Present, and Future. J. Paleontol. 71, 533–539 (1997).

Google Scholar

-

Alroy, J. Geographical, environmental and intrinsic biotic controls on Phanerozoic marine diversification. Palaeontology 53, 1211–1235 (2010).

Google Scholar

-

Foote, M., Cooper, R. A., Crampton, J. S. & Sadler, P. M. Diversity-dependent evolutionary rates in early Palaeozoic zooplankton. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 285, 20180122 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Fan, J. et al. A high-resolution summary of Cambrian to Early Triassic marine invertebrate biodiversity. Science 367, 272–277 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Clapham, M. E. Conservation evidence from climate-related stressors in the deep-time marine fossil record. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 374, 20190223 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Finnegan, S. Paleontological baselines for evaluating extinction risk in the modern oceans. Science 348, 567–570.

-

The Paleobiology Database. www.paleobiodb.org.

-

Geobiodiversity Database. www.geobiodiversity.com.

-

Hopkins, M. J. The environmental structure of trilobite morphological disparity. Paleobiology 40, 352–373 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Klug, C., De Baets, K., Naglik, C. J. & Waters, J. A new species of Tiaracrinus from the latest Emsian of Morocco and its phylogeny. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 59, 135–145 (2014).

-

Holland, S. M. & Sclafani, J. A. Phanerozoic diversity and neutral theory. Paleobiology 41, 369–376 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Balseiro, D. & Powell, M. G. Carbonate collapse and the late Paleozoic ice age marine biodiversity crisis. Geology 48, 118–122 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Moharrek, F. et al. Diversification dynamics of cheilostome bryozoans based on a Bayesian analysis of the fossil record. Palaeontology 65, e12586 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Albouy, C. et al. The marine fish food web is globally connected. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1153–1161 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Cole, S. R. & Hopkins, M. J. Selectivity and the effect of mass extinctions on disparity and functional ecology. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf4072 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Foote, M. Perimeter-Based Fourier Analysis: A New Morphometric Method Applied to the Trilobite Cranidium. J. Paleontol. 63, 880–885 (1989).

Google Scholar

-

Foote, M. Morphological and taxonomic diversity in a clade’s history: the blastoid record and stochastic simulations. Contrib. Mus. Paleontol. Univ. Mich. 28, 101–140.

-

Foote, M. Contributions of Individual Taxa to Overall Morphological Disparity. Paleobiology 19, 403–419 (1993).

Google Scholar

-

Foote, M. The Evolution of Morphological Diversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 28, 129–152 (1997).

Google Scholar

-

Foote, M. Discordance and concordance between morphological and taxonomic diversity. Paleobiology 19, 185–204 (1993).

Google Scholar

-

Roy, K. & Foote, M. Morphological approaches to measuring biodiversity. Trends Ecol. Evol. 12, 277–281 (1997).

Google Scholar

-

Neige, P. Spatial patterns of disparity and diversity of the recent cuttlefishes (Cephalopoda) across the Old World. J. Biogeogr. 30, 1125–1137 (2003).

Google Scholar

-

Benton, M. J. Exploring macroevolution using modern and fossil data. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 282, 20150569 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Maestri, R., Monteiro, L. R., Fornel, R., de Freitas, T. R. O. & Patterson, B. D. Geometric morphometrics meets metacommunity ecology: environment and lineage distribution affects spatial variation in shape. Ecography 41, 90–100 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Gonzalez, P. N. et al. Description and Analysis of Spatial Patterns in Geometric Morphometric Data. Evol. Biol. 46, 260–270 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Jablonski, D. Developmental bias, macroevolution, and the fossil record. Evol. Dev. 22, 103–125 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Madin, J. S. et al. The Coral Trait Database, a curated database of trait information for coral species from the global oceans. Sci. Data 3, 160017 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Davies, C. H. et al. A database of marine phytoplankton abundance, biomass and species composition in Australian waters. Sci. Data 3, 160043 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Raja, N. B., Dimitrijević, D., Krause, M. C. & Kiessling, W. Ancient Reef Traits, a database of trait information for reef-building organisms over the Phanerozoic. Sci. Data 9, 425 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Hopkins, M. J., Wagner, P. J. & Jordan, K. J. Permian trilobites and the applicability of the “living fossil” concept to extinct clades. Front. Ecol. Evol. 11, (2023).

-

Suárez, M. G. & Esteve, J. Morphological diversity and disparity in trilobite cephala and the evolution of trilobite enrolment throughout the Palaeozoic. Lethaia 54, 752–762 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Holmes, J. D. Contrasting patterns of disparity suggest differing constraints on the evolution of trilobite cephalic structures during the Cambrian ‘explosion. Palaeontology 66, e12647 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Bault, V. et al. Rise and fall of the phacopids: the morphological history of a successful trilobite family. Palaeontology 66, e12673 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Drage, H. B. Trilobite moulting behaviour variability had little association with morphometry. bioRxiv 2022.12.12.520015, https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.12.520015 (2022).

-

Adrain, J. M. et al. Trilobites. in The Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event (eds. Webby, B. D., Paris, F., Droser, M. L. & Percival, I. G.) 231–254 (Columbia University Press, 2004).

-

Zhang, S., Fan, J., Morgan, C. A., Henderson, C. M. & Shen, S. Quantifying the middle–late Cambrian trilobite diversity pattern in South China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 570, 110361 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Bault, V., Crônier, C. & Monnet, C. Morphological disparity trends in Devonian trilobites from North Africa. Palaeontology 65, e12623 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Lerosey-Aubril, R. & Feist, R. Quantitative Approach to Diversity and Decline in Late Palaeozoic Trilobites. in Earth and Life (ed. Talent, J. A.) 535–555, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-3428-1_16 (Springer Netherlands, 2012).

-

Paterson, J. R. The trouble with trilobites: classification, phylogeny and the cryptogenesis problem. Geol. Mag. 157, 35–46 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Bault, V., Balseiro, D., Monnet, C. & Crônier, C. Post-Ordovician trilobite diversity and evolutionary faunas. Earth-Sci. Rev. 230, 104035 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Zelditch, M. L., Swiderski, D. L. & Sheets, H. D. Geometric Morphometrics for Biologists: a primer. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-386903-6.00001-0 (Elsevier, 2012).

-

Hopkins, M. & Pearson, J. Non-linear ontogenetic shape change in Cryptolithus tesselatus (Trilobita) using three-dimensional geometric morphometrics. Palaeontol. Electron. 19.3, 1–54 (2016).

-

Adams, D. C. & Otárola-Castillo, E. geomorph: an r package for the collection and analysis of geometric morphometric shape data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4, 393–399 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Rohlf, F. J. The tps series of software. Hystrix Ital. J. Mammal. 26, 9–12 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Baken, E. K., Collyer, M. L., Kaliontzopoulou, A. & Adams, D. C. geomorph v4.0 and gmShiny: Enhanced analytics and a new graphical interface for a comprehensive morphometric experience. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12, 2355–2363 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Adams, D. C., Rohlf, F. J. & Slice, D. E. Geometric morphometrics: Ten years of progress following the ‘revolution’. Ital. J. Zool. 71, 5–16 (2004).

Google Scholar

-

Olsen, A. M. & Westneat, M. W. StereoMorph: an R package for the collection of 3D landmarks and curves using a stereo camera set-up. Methods Ecol. Evol. 6, 351–356 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

R Core Team. R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. (2018).

-

Serra, F. et al. A dynamic and collaborative database for morphogeometric information of trilobites. Repositorio Digital UNC https://rdu.unc.edu.ar/handle/11086/547753 (2023).

-

Serra, F. et al. TriloMorph. balsedie/trilomorph: stable_release (v1.0). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8033445 (2023).

-

The Official YAML Web Site. www.yaml.org.

-

Claude, J. Morphometrics with R. (Springer, 2008).

-

Waisfeld, B. G. & Vaccari, N. E. Trilobites. in Ordovician Fossils of Argentina (ed. Benedetto, J. L.) 295–410 (Secretaría de Ciencia y Tecnología – Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, 2003).

-

Waisfeld, B. G., Vaccari, N. E., Chatterton, B. D. E. & Edgecombe, G. D. Systematics of Shumardiidae (Trilobita), with new species from the Ordovician of Argentina. J. Paleontol. 75, 827–859 (2001).

Google Scholar

-

Vaccari, N. E. & Waisfeld, B. G. Kainella Walcott, 1925 (Trilobita, Ordovícico Temprano) en el noroeste de Argentina y sur de Bolivia. Paleontología sistemática. Ameghiniana 47, 273–292 (2010).

Google Scholar

-

Meroi Arcerito, F. R., Waisfeld, B. & Balseiro, D. Diversification of Asaphellus Callaway, 1877 (Asaphidae: Trilobita) during the Tremadocian in South West Gondwana (Cordillera Oriental, Argentina). Geodiversitas 37, 131–150 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Arcerito, F. R. M., Waisfeld, B. G., Vaccari, N. E. & Muñoz, D. F. High Resolution Trilobite Biostratigraphy for the Early Late Tremadocian (Tr2) Interval (Early Ordovician) Santa Rosita Formation, Argentine Cordillera Oriental. Ameghiniana 55, 531 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Rustán, J. J., Balseiro, D., Waisfeld, B., Foglia, R. D. & Vaccari, N. E. Infaunal molting in Trilobita and escalatory responses against predation. Geology 39, 495–498 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Rustán, J. J. & Vaccari, N. E. The Aulacopleurid Trilobite Maurotarion Alberti, 1969, in the Silurian-Devonian of Argentina: Systematic, Phylogenetic and Paleobiogeographic Significance. J. Paleontol. 84, 1082–1098 (2010).

Google Scholar

-

Rustán, J. J. & Balseiro, D. The phacopid trilobite Echidnops taphomimus n. sp. from the Lower Devonian of Argentina: insights into infaunal molting, eye architecture and geographic distribution. J. Paleontol. 90, 1100–1111 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Rustán, J. J. & Vaccari, N. E. A revision of the Devonian Malvinokaffric dalmanitid trilobite Dalmanitoides Delo, 1935, on the basis of new data from Argentina. Palaeontol. Electron. 15, 21 (2012).

-

Randolfe, E. A., Rustán, J. J. & Bignon, A. A taxonomic revision of the Early Devonian dalmanitid trilobite Kasachstania Maksimova, 1972 from central Kazakhstan. J. Paleontol. 94, 681–695 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Randolfe, E. A., Rustán, J. J. & Bignon, A. New dalmanitid trilobite taxa from the Lower Devonian of Argentina: comments on spinosity in endemic taxa from southern high paleolatitudes. Comptes Rendus Palevol 21, 17–38 (2022).

-

Rustán, J. J., Waisfeld, B. G. & Vaccari, N. E. The homalonotid trilobite Burmeisteria Salter, 1865 in the Lower Devonian of Argentina: new data in the context of southwestern Gondwana. J. Paleontol. 94, 498–512 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Serra, F., Balseiro, D. & Waisfeld, B. G. Morphospace trends underlying a global turnover: Ecological dynamics of trilobite assemblages at the onset of the Ordovician Radiation. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 615, 111448 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Bignon, A., Waisfeld, B. G., Vaccari, N. E. & Chatterton, B. D. E. Reassessment of the Order Trinucleida (Trilobita). J. Syst. Palaeontol. 18, 1061–1077 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Bignon, A., Corbacho, J. & López-Soriano, F. J. A revision of the first Asteropyginae (Trilobita; Devonian). Geobios 47, 281–289 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Bignon, A. & Crônier, C. Evolutionary modifications of ontogeny of three Dechenella species (Proetidae), from the Middle Devonian of the Ardenne Massif (France). J. Paleontol. 86, 558–566 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Bignon, A. & Crônier, C. The systematics and phylogeny of the Devonian subfamily Asteropyginae (Trilobita: Phacopida). J. Syst. Palaeontol. 12, 637–668 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Crônier, C. Morphological disparity and developmental patterning: contribution of phacopid trilobites. Palaeontology 56, 1263–1271 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Crônier, C., Feist, R. & Auffray, J.-C. Variation in the eye of Acuticryphops (Phacopina, Trilobita) and its evolutionary significance: a biometric and morphometric approach. Paleobiology 30, 471–481 (2004).

Google Scholar

-

Crônier, C., Bignon, A. & François, A. Morphological and ontogenetic criteria for defining a trilobite species: The example of Siluro-Devonian Phacopidae. Comptes Rendus Palevol 10, 143–153 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Crônier, C., Renaud, S., Feist, R. & Auffray, J.-C. Ontogeny of Trimerocephalus lelievrei (Trilobita, Phacopida), a representative of the Late Devonian phacopine paedomorphocline: a morphometric approach. Paleobiology 24, 359–370 (1998).

-

Crônier, C., Ariuntogos, M., Königshof, P., Waters, J. A. & Carmichael, S. K. Late Devonian (Famennian) phacopid trilobites from western Mongolia. Palaeobiodiversity Palaeoenvironments 101, 707–723 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Kim, K., Sheets, H. D., Haney, R. A. & Mitchell, C. E. Morphometric analysis of ontogeny and allometry of the Middle Ordovician trilobite Triarthrus becki. Paleobiology 28, 364–377 (2002).

Google Scholar

-

Sheets, H. D., Kim, K. & Mitchell, C. E. A combined landmark and outline-based approach to ontogenetic shape change in the Ordovician trilobite Triarthrus becki. in Morphometrics: Applications in Biology and Paleontology (ed. Elewa, A. M. T.) 67–82, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-08865-4_6 (Springer, 2004).

-

Fusco, G., Hughes, N. C., Webster, M. & Minelli, A. Exploring developmental modes in a fossil arthropod: growth and trunk segmentation of the trilobite Aulacopleura konincki. Am. Nat. 163, 167–183 (2004).

Google Scholar

-

Crônier, C. & Fortey, R. A. Morphology and ontogeny of an early Devonian phacopid trilobite with reduced sight from Southern Thailand. J. Paleontol. 80, 529–536 (2006).

Google Scholar

-

Webster, M. & Sheets, H. D. A Practical Introduction to Landmark-Based Geometric Morphometrics. Paleontol. Soc. Pap. 16, 163–188 (2010).

Google Scholar

-

MacLeod, N. Landmarks, Localization, and the Use of Morphometrics in Phylogenetic Analysis. in Fossils, Phylogeny, and Form: An Analytical Approach (eds. Adrain, J. M., Edgecombe, G. D. & Lieberman, B. S.) 197–233, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0571-6_6 (Springer US, 2001).

-

Webster, M. & Zelditch, M. L. Modularity of a Cambrian ptychoparioid trilobite cranidium: Modularity of trilobite cranidium. Evol. Dev. 13, 96–109 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Gendry, D., Courville, P., Saucède, T., Laffont, R. & Paris, F. Contribution of Morphometrics to the Systematics of the Ordovician Genus Neseuretus (Calymenidae, Trilobita) from the Armorican Massif, France. J. Paleontol. 87, 456–471 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Esteve, J., Gutiérrez-Marco, J. C., Rubio, P. & Rábano, I. Evolution of trilobite enrolment during the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event: insights from kinematic modelling. Lethaia 51, 207–217 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Whittington, H. B. Morphology of the exoskeleton. in Treatise on invertebrate paleontology. Part O, Arthropoda 1, Trilobita revised (ed. Kaesler, R. L.) vol. 1 1–85 (The Geological Society of America & The University of Kansas, Boulder, Colorado & Lawrence, 1997).

-

Fortey, R. A. & Owens, R. M. Evolutionary history. in Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part 0, Arthropoda 1, Trilobita (ed. Kaesler, R. L.) 250–287 (The Geological Society of America & University of Kansas, Boulder, Colorado & Lawrence, 1997).

-

Anderson, M. J. Distance-based tests for homogeneity of multivariate dispersions. Biometrics 62, 245–253 (2006).

Google Scholar

-

Klingenberg, C. P. MorphoJ: an integrated software package for geometric morphometrics. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 11, 353–357 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Slice, D. E. Morpheus et al., Java Edition (2013).

-

Hammer, O., Harper, D. A. T. & Ryan, P. D. PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 4, (2001).

-

Dryden, I. L. Shapes package. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Contributed package. (2021).

-

Bonhomme, V., Picq, S., Gaucherel, C. & Claude, J. Momocs: Outline Analysis Using R. J. Stat. Softw. 56, 1–24 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Gower, J. C. Generalized procrustes analysis. Psychometrika 40, 33–51 (1975).

Google Scholar

-

Rohlf, F. J. & Slice, D. Extensions of the Procrustes Method for the Optimal Superimposition of Landmarks. Syst. Zool. 39, 40 (1990).

Google Scholar

-

Bookstein, F. L. Morphometric Tools for Landmark Data: Geometry and Biology. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511573064 (Cambridge University Press, 1992).

-

O’higgins, P. The study of morphological variation in the hominid fossil record: biology, landmarks and geometry. J. Anat. 197, 103–120 (2000).

Google Scholar

-

Wills, M. A., Briggs, D. E. G. & Fortey, R. A. Disparity as an Evolutionary Index: A Comparison of Cambrian and Recent Arthropods. Paleobiology 20, 93–130 (1994).

Google Scholar

-

Ciampaglio, C. N., Kemp, M. & McShea, D. W. Detecting Changes in Morphospace Occupation Patterns in the Fossil Record: Characterization and Analysis of Measures of Disparity. Paleobiology 27, 695–715 (2001).

Google Scholar

-

Guillerme, T. et al. Disparities in the analysis of morphological disparity. Biol. Lett. 16, 20200199 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Guillerme, T. dispRity: A modular R package for measuring disparity. Methods Ecol. Evol. 9, 1755–1763 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Korn, D., Hopkins, M. J. & Walton, S. A. Extinction space-a method for the quantification and classification of changes in morphospace across extinction boundaries: extinction space. Evolution 67, 2795–2810 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. (2022).

-

Gon, S. M. III A pictorial guide to the Orders of trilobites. http://www.trilobites.info/. (2009).

-

Scotese, C. R. PALEOMAP website. http://www.scotese.com (2002).

-

Müller, R. D. et al. GPlates: Building a Virtual Earth Through Deep Time. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 19, 2243–2261 (2018).

Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

This publication is part of an ECOS Sud-MinCyT project co-financed by the Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires Étrangères (MEAE) and the Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche et de l’Innovation (MESRI) on behalf of France and the Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación on behalf of Argentina (n°A17A01). We wish to express our appreciation to the editorial team, Dr Harriet B. Drage and an anonymous reviewer whose insightful comments greatly improved this contribution. A.B, B.G.W, D.B, D.F.M, E.N.V, E.R, F.S., and J.J.R. acknowledge supporting facilities of the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas and Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. E.R would like to thank the Národní Muzeum for allowing, in collaboration with Synthesys+, access to specimens included in TriloMorph. The authors would like to thank Axelle Zacaï (PALEVOPRIM, Poitiers Univ., France) and Nicolás Wolovick (FaMAF, UNC) for useful discussions regarding the database structure, and to Sam Gon III for allowing the use of his figures. This is Paleobiology Database official publication number #473. This contribution has been possible thanks to the financial support of the international collaboration ECOS-Sud project n°A17A01 (France-Argentina). Financial support for this study was further provided by the ANPCyT–FONCyT PICT 2019-01818 to FS and PICT-2021-I-A-00968 to DB; CONICET PIP 202111220200103192 to BGW and DB; and the Synthesys + Project (Transnational Access) and the Paleontological Society (Sepkoski Award) to ER.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C. and B.G.W. led the project and were responsible for funding support. C.C., B.G.W., A.B., J.J.R., F.S., N.E.V. and D.B. designed the landmarking protocol. D.B., A.B., C.C., F.S. and D.F.M. designed the dataset. F.S., D.B., E.R., D.F.M., V.B, J.J.R., N.E.V., A.B., B.G.W. and C.C. organised and carried out the data collection. C.M. wrote the R functions used to perform the morphological analyses. C.M. analysed the data with input from F.S. and D.B. D.B. designed and built the Github repository with input from F.S. F.S., D.B. and C.M. wrote the manuscript with input from all the authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

TriloMorph R functions

TriloMorph workflor in R

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Serra, F., Balseiro, D., Monnet, C. et al. A dynamic and collaborative database for morphogeometric information of trilobites.

Sci Data 10, 841 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02724-9

-

Received: 14 June 2023

-

Accepted: 06 November 2023

-

Published: 29 November 2023

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02724-9