VIP hunters including senior Russian officials and wealthy businessmen appear increasingly keen to target protected animals and areas across the country.

These efforts, when combined with poor government oversight, could threaten the survival of the country’s rare species, experts told The Moscow Times.

“Since the tsarist era, hunting has been seen in Russia as an elite form of relationship building. Bringing a high-ranking official on a hunt is prestigious and beneficial,” said a Russian environmental expert who requested anonymity due to their affiliation with a group targeted by the authorities.

One of the highest-ranking professional hunters is former Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, who has reportedly hunted in the company of President Vladimir Putin in Siberia and the Far East on several occasions.

“Trophy hunting of endangered animals also happens,” the expert said. “Sometimes it’s blatant — they [hunters] simply do it illegally — and sometimes semi-legally.”

In recent years, lawmakers and officials have taken a number of steps to loosen hunting regulations.

In March, officials in the northwestern republic of Karelia allocated a portion of land that was previously part of the Ladoga Skerries National Park as hunting grounds after its protected status was removed last year.

Experts warn that this reallocation will prove disastrous for the national park’s ecosystem. One businessman who stands to reap benefits from it is Russian tycoon Roman Abramovich, who owns a real estate management firm in the area, according to the environmental news outlet Smola.

In 2021, Russia passed amendments allowing protected species to be hunted in “exceptional cases” including scientific purposes or to prevent disease in domestic animals.

Activists say that this legal tweak has created a loophole for affluent hunters to kill rare species for trophies under the guise of scientific research, simply by buying off the necessary justification papers.

The Russian Club of Mountain Hunters, a nonprofit advocating for legal trophy hunting of hoofed animals in the wild, maintains lists of trophies for which participants can earn points and advance in the club’s Hunters’ Ranking.

Besides non-protected species, these lists feature several named in Russia’s Red Book of threatened species such as the snow sheep, Altai argali and wild goat.

State Duma deputy Vladislav Reznik, who co-authored the amendments permitting the hunting of Red Book animals, currently tops the club’s Hunters’ Ranking.

Along with its leader, former FSB special forces operative Eduard Bendersky, the club counts former presidential aide and ex-minister Sergei Yastrzhembsky, current Russian deputies and prominent businessmen among its members.

The Russian Club of Mountain Hunters did not respond to The Moscow Times’ request for comment.

Controversial pastime

Despite being legal in many countries, trophy hunting is a divisive practice, with its critics questioning the morality of killing animals for recreation and arguing that it harms conservation efforts.

Hunters maintain that their hobby helps maintain ecosystem balance and that hunting fees and duties can help fund nature conservation.

Ex-minister Yastrzhembsky voiced similar sentiments, arguing that wildlife conservation and trophy hunting “must go hand in hand.”

“This is exactly what our radicals don’t understand,” Yastrzhembsky said in 2021, referring to these groups with a Russian-language portmanteau of “zoo” and “schizophrenic.”

“Wildlife cannot be fetishized, treated as some deity to be worshiped while ignoring the problems that arise with a lack of regulation of the excess population of predators — wolves or bears. After all, this is a threat to human life,” he continued.

Beyond the ethical concerns, environmentalists warn that trophy hunting is not as sustainable as its proponents say.

Even when it complies with the law, trophy hunting can still harm biodiversity by eliminating the largest animals, which risks depopulating certain species, said Mikhail Yurchenko, an expert from the International Socio-Ecological Union NGO.

“Any hunting disrupts the balance in the ecosystem and pollutes the surrounding environment with hunting ammunition. The noise of gunfire also harms animals, especially during the spring hunting season,” Yurchenko told The Moscow Times.

mossafariclub.ru

As an additional stressor for wildlife, hunting can lead to unpredictable consequences when combined with other factors, the anonymous expert said.

In Russia’s Far East, Siberian tigers are increasingly encroaching into villages, killing humans or snatching dogs due to a lack of prey in the forests.

“At first, wild boars were the tigers’ main hunting target,” the anonymous environmental expert explained. “Then there was an outbreak of African swine fever, which, along with hunting, significantly reduced the main wild boar population.”

“The tigers started to switch to other prey such as Manchurian elk, roe deer and sika deer — but they were scarce, as hunters had already taken them down.”

Experts say decades of forest clearance in the area has further exacerbated the tigers’ lack of food sources.

Russia’s wildlife management is plagued by poor governmental oversight, unreliable data on population numbers of species permitted to be hunted and a shortage of hunting inspectors, the expert said.

“I know of certain situations where a wealthy individual takes a huge chunk of forest for themselves as a hunting ground. It’s just a thrill for them. And maybe once a year, they’ll come there with friends to shoot some wild boar,” they said.

“On the other hand, some completely exploit it, shoot everything there and then go bankrupt. Unfortunately, this is not regulated at all. It should be monitored by game inspectors, of which there are very few.”

Yet others, echoing officials’ anti-Western rhetoric, have pointed the finger at the West for the threats to Russia’s wildlife.

Foreign visits decline

Amid the wider anti-Western sentiment in Russia, some media outlets and Telegram channels have recently slammed Russian firms that organize hunting trips for foreigners.

“While the people of Russia firmly resist various unlawful sanctions imposed by unfriendly states, citizens of these very countries continue to destroy Russian wildlife. They ‘take the beast’ and effortlessly obtain permits to export trophies beyond Russia’s borders,” the Zelyony Zmiy (Green Snake) environmental Telegram channel said this year.

“A pressing question is if Russia needs to provide this sort of ‘service shooting range’ for the collective West in the current geopolitical climate,” it continued.

huntportal.ru

Several factors make Russia a destination for foreigners interested in trophy hunting, Sergei Shushunov from the U.S.-based Russian Hunting Agency, which organizes hunting, fishing and adventure tours to Russia, told The Moscow Times.

The country boasts large areas of untouched natural habitats teeming with vibrant wildlife, lower prices for hunting some species compared to the U.S. and Canada and the opportunity to secure trophies in the wild rather than on game farms, Shushunov said.

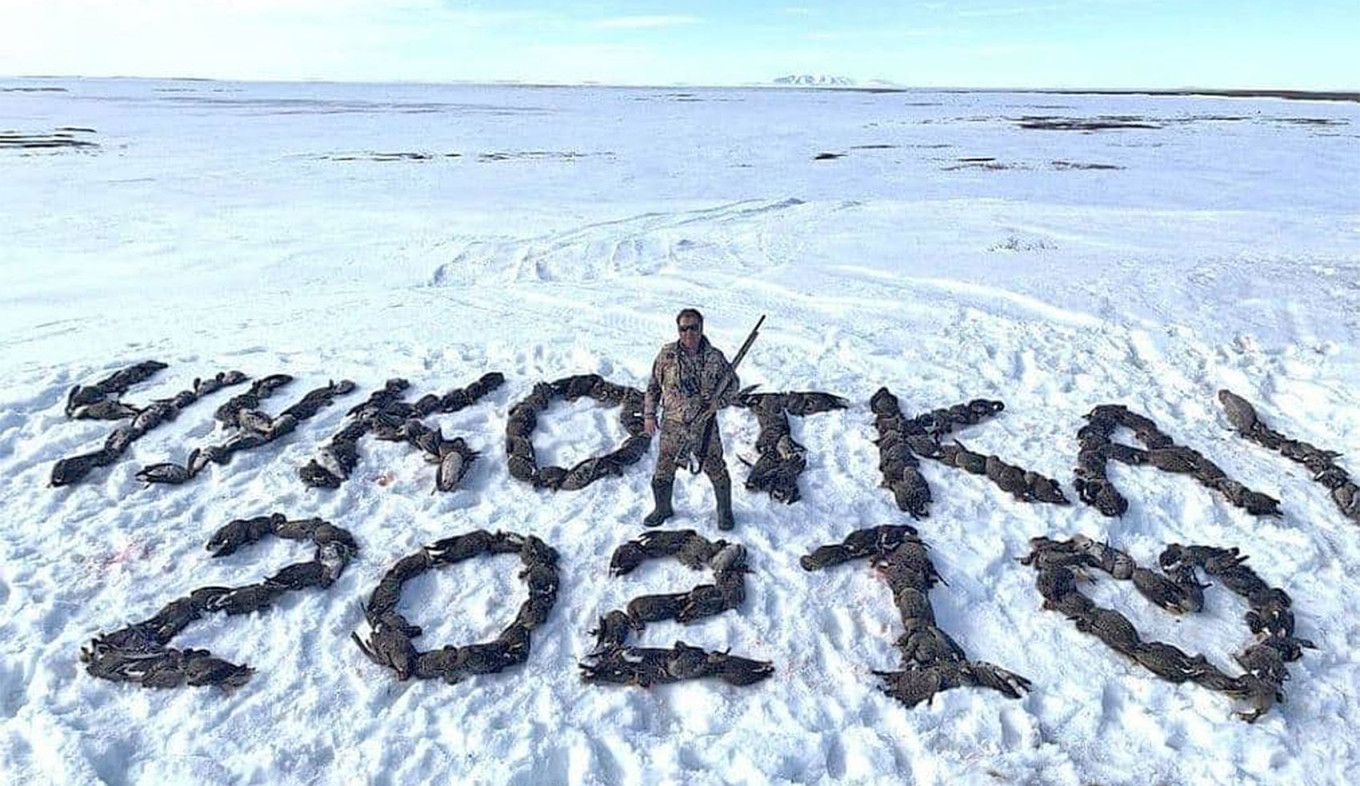

Russia is also home to a number of exotic species such as the Asiatic black bear, Caucasian chamois, snow sheep and Siberian ibex, as well as capercaillie and ducks that can be taken when they are in prime plumage, unlike elsewhere in the Northern Hemisphere.

Finally, foreign hunters may have greater success rates in Russia because its lands are not as overhunted as those of other countries and the guides’ compensation depends on the number of trophies taken, Shushunov said.

However, the Covid-19 pandemic and the 2022 invasion of Ukraine have reduced visits by foreign hunters, three hunting tour organizers told The Moscow Times.

Estimates suggest that about 600-700 foreign hunters traveled to Russia in 2021, down from over 2,000 per year in the early 2000s.

“Before Covid, we had prepayments for tours booked three to four years in advance. [Since 2022] we have faced complete cancellations of tours. There are still some clients … but I think they will also postpone their trips,” said Anatoly Turushev, general director of Kamchatka Trophy Hunts.

“We are refusing to make arrangements until the war is over, but many still want to come. The traffic is down 90%,” said a representative of a U.S.-based firm that organized hunting trips to Russia from 1985 until 2022. They spoke on condition of anonymity to avoid putting Russia-based staff at risk by discussing the war’s impacts on their business.

Social media

The U.S.-based firm’s representative said it was “nonsense” to say that foreign trophy hunters should be concerned by Russia’s poor governmental oversight of wildlife.

“Wildlife in Russia is well managed and the resource is so vast that the relatively small number of hunters does not affect the population of most game species in a significant way,” they said.

“Poaching is a bigger problem, but of marginal effect, due to the size of your country [Russia] and the relatively small population. Wealthy Russians take advantage of everything, as you already know.”

Given the reduced numbers of foreign hunters, domestic hunters, especially poachers or those with powerful lobbying capacities, appear more likely to pose a risk to Russia’s rare species — despite what anti-Western voices say.

“Trophy hunting, whether domestic or foreign, poses a threat to biodiversity, especially when combined with rampant poaching and inadequate protection — as is the case in many areas [in Russia],” the anonymous Russian environmental expert said.

“Authorities tend to react only when catastrophic consequences begin to unfold.”

… we have a small favor to ask. As you may have heard, The Moscow Times, an independent news source for over 30 years, has been unjustly branded as a “foreign agent” by the Russian government. This blatant attempt to silence our voice is a direct assault on the integrity of journalism and the values we hold dear.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. Our commitment to providing accurate and unbiased reporting on Russia remains unshaken. But we need your help to continue our critical mission.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It’s quick to set up, and you can be confident that you’re making a significant impact every month by supporting open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Once

Monthly

Annual

Continue

Not ready to support today?

Remind me later.

×

Remind me next month

Thank you! Your reminder is set.