Lire en français

In a world where populism and anti-science agendas make headlines daily, policymakers, research funders, scientists, and science communicators have voiced fears about a crisis of public trust in science. This has led to widespread calls to restore and renew trust. In democratic societies, public trust in science is vital to legitimise funding and help citizens make informed decisions about issues where scientific evidence is instrumental, such as health, nutrition, technology, and sustainability.

Despite concerns about low public trust in science, a recent global study published in Nature Human Behaviour1 shows that most people in 68 countries worldwide trust scientists.

The study was part of the TISP Many Labs project led by Viktoria Cologna and Niels G. Mede. It involved 241 researchers from 169 research institutions worldwide, including 12 researchers from 10 African research institutions. Between November 2022 and August 2023, nearly 72,000 respondents across 68 countries participated, including more than 6,000 participants from 12 African countries (Botswana, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia Ghana, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, South Africa, and Uganda). The samples were weighted according to national distributions of age, gender, education, and country sample size.

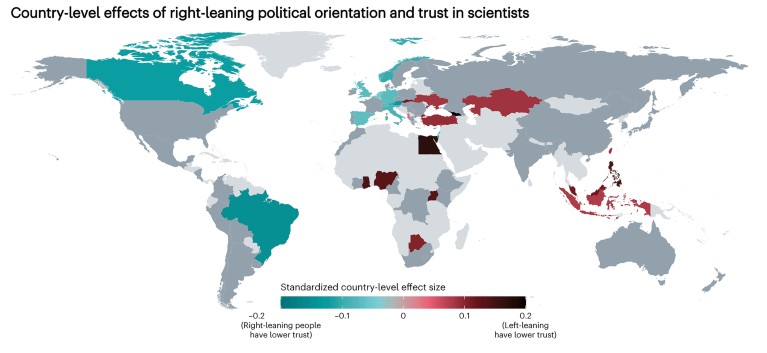

The study confirmed moderately high trust in scientists and showed that, on average, most people agreed that scientists have high competence, benevolence and integrity. The findings indicate that trust is slightly higher for women, older people, residents of urban (versus rural) regions, and people with high incomes, religiosity, formal education, and liberal and left-leaning political views.

Three African countries were in the top five countries where scientists are most trusted: Egypt, Nigeria, and Kenya. This finding contradicts assumptions that trust in scientists is lower in African countries.

Most people in the 12 African countries included in the study believed that scientists should prioritise improving public health, solving energy problems, and reducing poverty – which conforms with the priorities of people in other parts of the world. However, across the 68 countries, most respondents wanted scientists to focus less on defence and military technology, but these topics remain relatively high priorities for most people in Africa.

Across all countries in the survey, 83% of respondents agreed that scientists should communicate effectively about their research, and most wanted scientists to engage more with society. This reflects a broader expectation that scientific knowledge should be more accessible and transparent and that scientists should be more open to input from society. In Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Uganda, there is a notably high demand for scientists to engage with the public. Respondents in Nigeria and Botswana expressed strong support for scientists taking an active role in policy advocacy, in contrast with respondents from Egypt and Morocco, who exhibited comparatively more opposition to scientists’ direct engagement in advocacy. Similarly, in Ethiopia, about a third of respondents were sceptical about scientists working closely with politicians to integrate scientific results into policymaking.

Science communication scholars generally acknowledge that citizens should not be expected to trust science blindly, but that informed trust is desirable. To achieve informed trust, science should be visible and accessible, and people must be able to assess the credibility of information about science-related topics so that they can distinguish between credible sources and mis- or disinformation. In a scientifically literate society, science becomes integrated into conversations, and citizens have opportunities to have their voices heard about the implications and applications of science and scientific research.

Most national and multi-country surveys of public attitudes to science, including public trust in scientists, focus on countries from the global north. However, since trust in scientists is influenced by numerous societal characteristics, including education, politics, religion, and science-related populism, it is essential to have insights from under-represented regions in Africa, Latin America, and Asia, providing crucial insights to science leaders and policymakers in these world regions. This study provides a baseline for understanding and monitoring public trust in scientists in Africa, and we hope that it can be repeated in future years and extended to more countries on the continent.

While this study provides an overall positive picture of public trust in science, it is important to remember that it evolves over time and can quickly erode or disintegrate in response to science-related crises or scandals. Since the study’s findings clearly show that Africans want scientists to communicate more effectively and engage with society meaningfully, this is a clear and timely call to action for scientists on the continent to make themselves and their work more visible and accessible. Science policymakers and funders should also heed this call and support scientists who go the extra mile in public communication and engagement with funding and recognition.

Find out more about this research project at https://www.tisp-manylabs.com/ and explore the data at https://www.tisp-manylabs.com/explore-tisp-data