WeWork as we know it is gone. Once valued at $47bn (£38bn), on 6 Nov, the global coworking company filed for Chapter 11 in New Jersey, US. With the news, its share price quickly tumbled, leaving the business valued at less than $50m (£41m). Although some locations will remain open, WeWork has begun closing offices around the world.

The company’s collapse has been spectacular, in part due to the riveting story of its rise and fall, documented on screen in a 2022 miniseries with Anne Hathaway and Jared Leto. Its name looms large in the public imagination, where “WeWork” has become practically synonymous with “coworking”, like “Kleenex” to “tissue” or “Google” to “search”.

The coworking world stands to feel ripples in the wake of WeWork’s high profile bankruptcy. Yet, the company’s recent challenges come at a time of quiet but historic growth in office-share world. Experts say that as WeWork fades, the need and desire for coworking will remain – and other players stand poised to seize the opportunity.

WeWork’s failings

One significant reason WeWork’s downfall may not disrupt the coworking industry is the nature of its failings, which largely pertain to its real estate holdings. Many successful coworking providers choose to partner with commercial landlords to provide their brand’s suite of amenities and membership perks in exchange for a flat fee or a share of the profits generated from membership dues. WeWork, however, took on a series of long-term leases and collected all the membership revenue directly. The model enabled them to enjoy more of the upside, but also exposed them to more risk.

At its peak, WeWork was holding nearly $19bn (£15.2bn) in debt to support 777 locations in 39 countries, the majority of which were on long-term leases the company expected to pay by collecting members’ fees. The pandemic, however, meant users cancelled their memberships, cutting off the funds WeWork needed to pay rent.

But experts say the Covid-19 crisis alone didn’t kill WeWork. “It wasn’t the pandemic that broke WeWork, it was their business model,” believes John Arenas, CEO of coworking company Serendipity Labs, which operates in the US. “I’ve been through four recessions in this industry in 30 years – and a pandemic, so that’s five – and a long-term lease is longer than the cycle – it’s just a mismatch that way.” (Arenas, who has worked in the space since the 90s, has doubted the viability of WeWork’s model since at least 2014.)

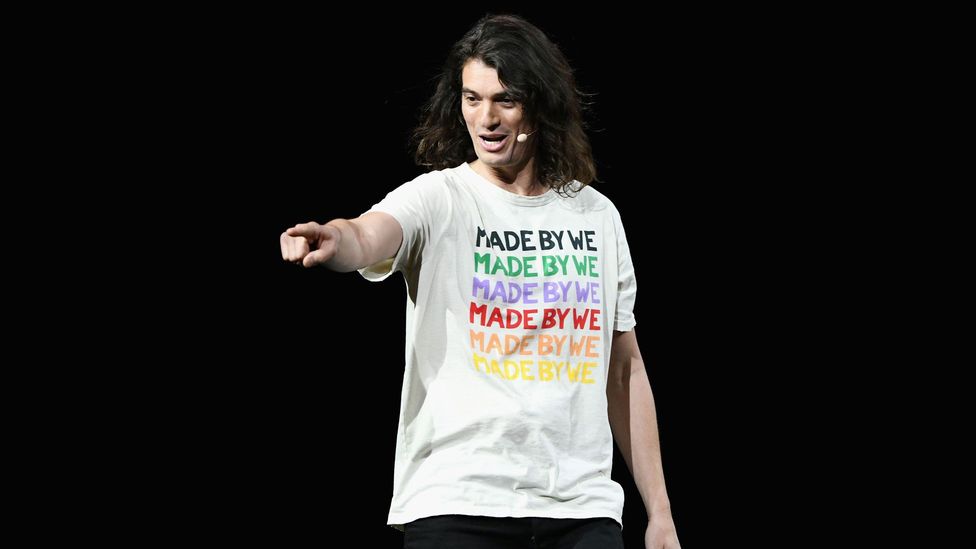

Adam Neumann, WeWork’s co-founder and former CEO, has been in the public spotlight as the company rose to prominence and subsequently fell (Credit: Getty Images)

A hunger for coworking

Despite WeWork’s troubles, experts believe that the coworking industry’s future is very bright. Colorado, US,-based Sara Sutton, CEO and founder of remote-job service FlexJobs, says the normalisation of coworking as a way to work has set up shared office arrangements to be more relevant than ever.

“Prior to the pandemic, there was so much evangelising that still needed to be done about why hybrid and remote work should be integrated into organisations,” she says. “We don’t have to evangelise that anymore. Everyone knows it’s established, and organisations are now formalising their remote or hybrid stances.”

Sutton says coworking spaces were traditionally popular with freelancers and those who work remotely but don’t have a productive home-office setup. While those cohorts still exist, she says coworking businesses are also seeing more demand from the organisations that are downsizing or eliminating their permanent real estate footprints in the wake of the remote work revolution.

“Coworking spaces offer flexibility, and a great opportunity for social interaction and community, which are going to be very important to offset some of the elements of remote work that people are increasingly aware of, like feeling lonely or craving social interaction,” she says. “Remote organisations are leaning more heavily on [flexible] workspace as an integrated part of their strategy, offering subsidies or actually having teams in the same area using coworking spaces as a local headquarters.”

Workers are also finding coworking spaces increasingly fitting into their new remote-work lives. Mark Dixon, founder and CEO of IGW, the parent company of global coworking-space network Regis, says a growing segment of customers now treat access to such spaces like a gym membership: they’re looking for perks, facilities, social programmes and amenities, though only a small fraction of members utilise the space at a time.

Additionally, says Dixon, many of their customers – one million of them, many of whom primarily work from home – are also increasingly taking advantage of the company’s virtual offices instead of physical spaces, in which “we do all their administration, answer their calls, deal with all their admin”. These workers also get to drop into any building as they want. “This has seen significant growth over the past years, as a direct result of this move to a more nomadic workplace.”

Largely, set-ups like these are becoming increasingly appealing and play an important post-pandemic role by enabling a more efficient hybrid-work experience: the best of the office, when and where workers want it. And Dixon believes they do, indeed want it – he’s never been more bullish on the industry’s future. As WeWork navigates their bankruptcy filing, IWG is reporting record revenues.

Many experts in the coworking space believe shared offices are still thriving and hotly desired (Credit: Alamy)

Filling WeWork’s vacancy

With the demand for coworking on the rise, WeWork’s downfall may create opportunities for other coworking space providers, especially as workers’ preferences change.

Although WeWork may be the most recognisable name in the industry – the synonym for coworking in common parlance – many companies have had a foothold in the space for years, just with fewer headlines, controversies and mini-series to boot.

Founded 35 years ago, Regus is among these companies with steady market presence. “We’re in the same industry, we’re in the same segment, but they’re coming at it from a different direction,” says Dixon, who notes IWG holds more than 4,000 workspaces in 120 countries. “[WeWork] is very concentrated in a few cities, so the difference is we’ve got a big spread-out network through the US and globally, in many cities.”

Dixon believes workers are no longer looking for offices in the heart of cities, as they did during WeWork’s 2010 launch, which was largely geared towards urban professionals looking for coffee-shop alternatives. Instead, he’s observed today’s remote workers are prioritising nixing the inner-city commute, subsequently seeking out hyperlocal spaces. Serendipity Labs takes a similar approach, standing up spaces in suburbs neighbouring major cities such as those surrounding New York.

Ultimately, Sutton says that since she began FlexJobs in 2007, pundits have been pointing to current events to suggest the age of flexibility is over. “At one point it was Yahoo! and Marissa Mayer, at another point it was IBM rescinding their remote work policy. People are always looking for a reason to say, ‘this is not going to happen’.”

WeWork’s recent challenges are giving her déjà vu. “The numbers show growth in interest in the coworking space, and I don’t see those suddenly dropping because of WeWork.”