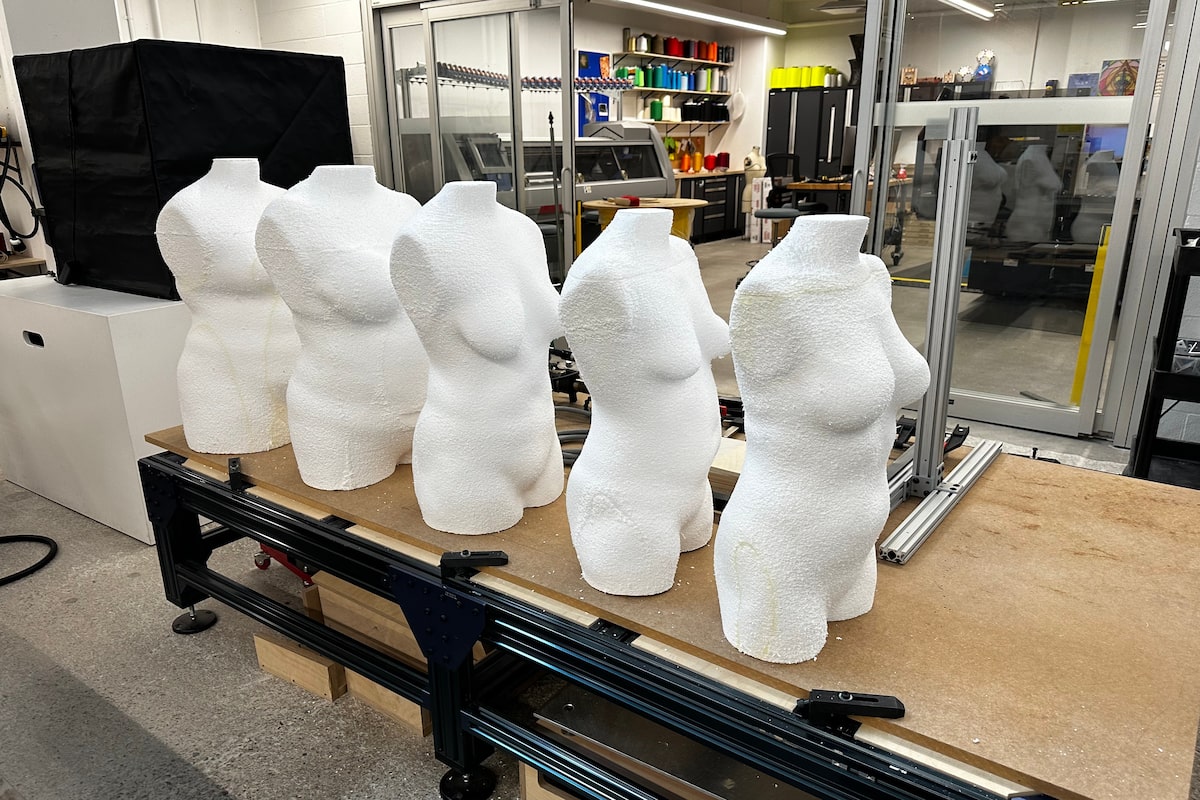

A pilot project at Toronto Metropolitan University has students designing body forms that challenge industry standards.Courtesy Toronto Metropolitan University

For many years, the body forms that fashion creatives and companies have used as part of their design practice – colloquially known by the gendered terms “Judies” and “Jimmies” – have been sculpted in a very narrow range of sizes and shapes. This is likely not a shock to the millions of people who stand outside the pervasively minuscule statures we’ve seen on runways and in clothing boutiques for decades, making us acutely aware of the absence of bodies that challenge these perimeters. Faculty and students at Toronto Metropolitan University, however, are on a mission to change these so-called standards with the help of 3-D scanning and robotic technology.

Caron Phinney, an assistant professor at TMU’s Fashion at The Creative School, is the lead for a pilot project involving five third- and fourth-year students from the University’s fashion design and performance programs that aims to augment the understanding of how diversity can be implemented into the fashion industry’s output from the earliest stages of the design process.

“It came out of a conversation I had with Dr. Ben Barry, who was then the chair at the School of Fashion, and professor Dr. Sandra Tullio-Pow,” Phinney says. “We spoke about what the fashion industry needed going forward, and what the future of fashion education is. How do students perceive and think about having to pattern draft for bodies outside of the [current] standard?”

Collaborating with another professor at TMU, PY Chau, and research assistant Delfina Russo, the group organized their thoughts around one key component in the design process – what garments are crafted on – and were eventually granted the go-ahead to work with the school’s Design and Technology Lab to innovate on their idea.

The participating students volunteered to have their bodies 3-D scanned, with that file’s information then input into a 3-D development software program called Rhino. After modifications were made there – the removal of arms and legs, for example, to resemble traditional body forms – the silhouette was milled into a foam form by a Kuka robotic arm. The scans were also imported to become avatars, and the students were then tasked with crafting a garment using both the physical and virtual renderings of their bodies as the model. The sartorial results have yet to be seen, but Phinney is already hopeful about the potential in this project’s outcome.

While she notes that most of the companies graduating students would imminently work for continue to operate with the existing standard for sizes and shapes, she says that the pilot project has already inspired those who’ve watched it come to fruition.

Students at TMU’s Fashion at The Creative School work with 3-D printed body forms based on their own bodies.Courtesy Toronto Metropolitan University

“I received an e-mail from a student saying that they’re interning for a company this summer, and that they believe that it would benefit in doing exactly what we were doing in the classroom,” Phinney says. “So, how do we empower students to go out and show companies the body of work from their four years here, and encourage them to take a chance on a young mind with fresh ideas to say that we can really do something different?”

The work being done at TMU reflects an adage often quoted by inclusivity advocates: You need to see it to be it. The lifestyle app Pinterest has taken this to heart with its introduction of a Body Type search function this past March.

Over the years, according to the company’s director of consumer product marketing, Rachel Hardy, user analytics have highlighted that in order to see people that reflected themselves, many Pinterest users needed to add modifiers to their search terms such as “plus size.”

“AI allows us to understand and identify diverse body types across 3.5 billion images,” she says, meaning folks can now use more individualized visual cues to guide their navigation of the platform instead of terms that could mean different things to different people.

Launched with four visual, unnamed categories for women’s fashion and wedding-related searches, the newly implemented AI technology allows users to select a body type that resembles theirs in order to populate applicable inspirational content. Hardy notes that while the initial functionality is focused on women, the company is committed to incorporating men, non-binary folks, people with disabilities and more options for age ranges in the future.

Hardy says that this increasingly personalized approach to using Pinterest is “resonating more than ever with Gen Z” users, though the beneficial ramifications are much farther reaching.

“When we make deliberate decisions about investing in the positive, more human side of AI, we can benefit as a business,” she says. “And brands can benefit too. We are seeing a higher engagement rate and increased shopping behaviour. I hope that the industry recognizes that by investing in this approach and understanding that doing good and doing good for business doesn’t have to be a trade-off.”