Abstract

The behavior of an organism is influenced by the complex interplay between its brain, body and environment. Existing data-driven models focus on either the brain or the body–environment. Here we present BAAIWorm, an integrative data-driven model of Caenorhabditis elegans, which consists of two submodels: the brain model and the body–environment model. The brain model was built by multicompartment models with realistic morphology, connectome and neural population dynamics based on experimental data. Simultaneously, the body–environment model used a lifelike body and a three-dimensional physical environment. Through the closed-loop interaction between the two submodels, BAAIWorm reproduced the realistic zigzag movement toward attractors observed in C. elegans. Leveraging this model, we investigated the impact of neural system structure on both neural activities and behaviors. Consequently, BAAIWorm can enhance our understanding of how the brain controls the body to interact with its surrounding environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

A multi-scale brain map derived from whole-brain volumetric reconstructions

Imaging whole-brain activity to understand behaviour

Connectomes across development reveal principles of brain maturation

Main

The behaviors of an organism are not simply the product of brain activity; rather, they emerge from a dynamic interplay among the brain, body and environment. To unravel the underlying neural control mechanisms, it is crucial to develop an integrative data-driven simulation that is constrained and parameterized by experimental data1,2 and integrates detailed models of the brain, body and environment. This model would accurately capture the characteristics and dynamics of the biological system being studied, thus both validating theories and making predictions for biological experiments.

Currently, there are specific data-driven models that simulate either the brain, such as the mouse primary visual cortex3, the mouse striatum4 and the rat somatosensory cortex5, or exclusively the body and environment to reproduce animal behaviors, such as neuromechanical models for Drosophila6 and rodents7. OpenWorm8 developed data-driven models of both the nervous system (c302, ref. 9) and the body (Sibernetic10) of Caenorhabditis elegans, which is a pioneering initiative in computational biology. However, the integration of these models is open loop, meaning they lack feedback from the environment. Therefore, no data-driven model currently meets all requirements of an integrative data-driven model, although such integration is urgently needed to progress our understanding of neural control mechanisms11.

An integrative data-driven model must meet certain requirements. First, it should incorporate a biophysically detailed brain model that has neural structures and neural activity patterns similar to those of the real organism. Second, it should consist of a realistic and high-performance body and environment model that facilitates easy behavior quantification. Third, and most crucially, the brain model should not only control the body model interacting with the virtual environment but also receive the feedback from the body and environment model, establishing a closed-loop interaction12,13.

We identified C. elegans as an exemplary model for developing such an integrative data-driven model that bridges brain, body and environment. It has completely mapped morphologies of all 302 neurons14,15 (in adult hermaphrodite), along with the connectome and synapse-level structure16,17,18. Recordings of single neural activity19,20,21,22,23 as well as brain-wide neural dynamics21,22,24 are available. Its body is well reconstructed, consisting of only 95 muscle cells. It also exhibits easily quantifiable behaviors, such as crawling, swimming and foraging25,26. Therefore, these simple structures and abundant data provide solid foundations for creating an integrative data-driven model.

In this Resource, we present an integrative data-driven model of C. elegans, BAAIWorm (Fig. 1). First, we developed a neural network model (brain model) of a C. elegans foraging neural circuit. It was built using biophysically detailed compartmental neuronal models, with compartments under 2 μm in length, encoding neural activity similar to live C. elegans. Second, we developed a body–environment model of C. elegans. The body model contained 96 muscles and enabled efficient real-time simulation at 30 frames s−1 and easy quantification of behaviors. Third, we established a closed-loop interaction between the brain model and the body–environment model to simulate C. elegans moving toward an attractor in a zigzag shape. Sensory neurons in the neural network model were activated by the attractor’s concentration in the environment. Muscles in the body model were controlled by motor neurons in the neural network model. Finally, we performed synthetic perturbations on the neural network model and suggested that the absence of a neurite or synaptic/gap junction disrupts global neural dynamics and hampers accurate forward motion.

BAAIWorm comprises two submodels: the neural network model and the body–environment model. The neural network model is biophysically detailed. Its neuron models are multicompartmental, exhibiting electrophysiological features similar to real C. elegans neurons. These neuron models are connected by synapses and gap junctions on neurites. An optimization tool is used to tune the weights and polarities of these connections. The body–environment model consists of a biomechanical body, a 3D fluid environment and a real-time simulation engine. The soft body is constructed using 3,341 tetrahedrons, with 96 muscles arranged from head to tail as actuators. The large-scale 3D environment allows the integration of various agents and elements including C. elegans, Escherichia coli (food) and fluid, and it provides a range of auxiliary tools for various lighting effects, visualization, tracking and behavior analysis. Real-time simulation is achieved through a FEM solver and simplified hydrodynamics. To achieve foraging behavior in C. elegans, the neural network senses the attractor’s concentration in the environment, performs neural computations to control muscles’ contraction and relaxation, and ultimately deforms the body to propel it toward the attractor.

BAAIWorm is open source and modular as the brain, body and environment models and their interactions can be independently modified, improved or extended by the scientific community. BAAIWorm will contribute to a deeper understanding of the intricate relationships between neural structures, neural activities and behaviors. This work also provides a framework for developing brain–body–environment models of other organisms. This approach paves the way for new avenues of systems biology and has the potential to progress traditional neural mechanism research.

Results

A data-driven biophysically detailed neural network model

Our neural network model of C. elegans contained 136 neurons that participated in sensory and locomotion functions, as indicated by published studies24,27,28,29,30,31. To construct this model, we first collected the necessary data including neural morphology, ion channel models, electrophysiology of single neurons, connectome, connection models and network activities (Fig. 2a). Next, we constructed the individual neuron models and their connections (Fig. 2b). At this stage, the biophysically detailed model was only structurally accurate (Fig. 2c), without network-level realistic dynamics. Finally, we optimized the weights and polarities of the connections to obtain a model that reflected network-level realistic dynamics (Fig. 2d). An overview of the model construction is shown in Fig. 2.

a, Experimental data collection to constrain models. These data include neural morphologies, ion channel models, electrophysiological recordings of single neurons, connectome, connection models and neural network activities. b, The construction of multicompartmental neuron models and connection models (synapses and gap junctions). c, The biophysically detailed C. elegans neural network model without functional neural activities. d, Optimization of the biophysically detailed C. elegans neural network model to achieve realistic network dynamics. Neurons are color-coded to represent membrane potential.

To achieve a high level of biophysical and morphological realism in our model, we used multicompartment models to represent individual neurons. The morphologies of neuron models were constructed on the basis of published morphological data9,32. Soma and neurite sections were further divided into several segments, where each segment was less than 2 μm in length. We integrated 14 established classes of ion channels (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2)33 in neuron models and tuned the passive parameters and ion channel conductance densities for each neuron model using an optimization algorithm34. This tuning was done to accurately reproduce the electrophysiological recordings obtained from patch-clamp experiments35,36,37,38 at the single-neuron level. Based on the few available electrophysiological data, we digitally reconstructed models of five representative neurons: AWC, AIY, AVA, RIM and VD5. The current-voltage characteristic curves (I–V curves) of our neuron models match those in the experiments (Supplementary Fig. 1). The optimized parameters of neuron models are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

These five neurons are representative for five different functional group: sensory neuron, interneuron, command neuron, head motor neuron and body motor neuron. They serve as the initial pool of digital neuron models to reconstruct other neurons in the neural network model. For neurons that are not representative neurons, their biophysical parameters were set the same as the representative neuron models that belonged to the same functional group. The referenced neurons of all neurons are listed in Supplementary Table 4. This approach allows us to achieve a high level of biophysical and morphological realism in our C. elegans neural network model with limited accessible experimental data.

For connections, we first modeled gap junctions as simple ohmic resistances, and synapses as continuously transmitting synapse, according to published models9,39,40,41,42. Then, we developed an algorithm to determine the number and locations of connections. The number of connections between two cells was from the cell adjacency matrix15 (Supplementary Fig. 2a). For each connection, we randomly assigned a distance following the neurite centroid distance distributions of synapse or gap junctions in an experiment17 (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Each connection linked two segments whose distance was closest to the randomly assigned distance. This approach allowed us to generate connections that were constrained by experimental connection numbers and distance distributions (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Supplementary Fig. 2d–f shows some examples of the connections between neurons in our neural network model. Most synapses and gap junctions were located on neurites that were relatively close to each other. Also, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2f, the constructed connections tended to cluster together, which followed the clustered organization principle in published research17,18.

To determine the polarities of synapses (excitatory or inhibitory) and the connection weights, we used a gradient-descent-based algorithm to minimize the mean squared error between simulation results and the optimization target. In this study, our optimization target was a Pearson correlation matrix of 65 identified neurons in a prior study24, where activity series were recorded through whole-brain single-cell-resolution Ca2+ imaging. Supplementary Fig. 3a shows the correlation matrices generated from our simulation and the experimental data. These two maps exhibited similar correlation strengths, whose mean squared error was only 0.076.

To further analyze the optimized neural network model, we conducted principal components analysis (PCA) on the membrane potential of the 65 identified neurons, involving the calculation of principal components (PCs) based on the covariance structure in the normalized data (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Upon sorting based on PC1, most neurons controlling forward locomotion (for example, AVB, VB and DB neurons) and backward locomotion (for example, AVA, VA and DA neurons) were distinctly classified into two groups (Supplementary Fig. 3b). The result of this analysis indicates that our trained neural network model accurately captures realistic neural dynamical relationships, and the dynamics of neurons encode functions similar to those observed in real C. elegans, to some extent. However, it is essential to clarify that this validation primarily confirms the effectiveness of our optimization algorithm rather than implying importance of the optimized parameters. These parameters represent just one of the possible solutions that can accurately reproduce the desired dynamics.

A high-performance body–environment model

Next, we developed the body–environment model of C. elegans. Our primary contributions are (1) modeling the soft body and muscles and solving soft-body deformation, (2) creating the three-dimensional (3D) simulation environment and solving soft-body–fluid interaction and (3) proposing a reference coordinate system for behavior analysis. The framework of this model is shown in Fig. 3a,b.

a, A schematic diagram of the C. elegans body model. The body was composed of tetrahedrons. Ninety-six muscle cells along four muscle strings served as actuators for soft-body deformation. Different colors on muscles indicate distinct muscle cells. The body was situated in a large 3D fluid environment and could move in the environment. Projective dynamics functions were used as the soft-body solver, and simplified hydrodynamics calculated thrust force and drag force on the body surface. b, An internal view of the body model, consisting of four muscle strings: VR, VL, DR and DL. c, The triangulated tetrahedron mesh of the body. d, Four muscle strings: VR (green), VL (yellow), DR (red) and DL (blue). The color intensity reflects the strength of muscle contraction, with high intensity indicating contraction and transparent intensity indicating relaxation. e, Tetrahedrons driven by four muscle strings: VR (green), VL (yellow), DR (red) and DL (blue). f, Deformation of the soft body. Blue tetrahedrons are increasing their volume whereas red ones are decreasing. g,h, The thrust force (g) and drag force (h) on the body surface. Red indicates strong force, and blue indicates weak force. i, Positions and velocities of the body at four moments. The body was moving from left to right. Color indicates velocities, with red representing fast and blue representing slow.

The body model was built with tetrahedral mesh, including 984 vertices, 3,341 tetrahedrons and 1,466 triangles on the body surface (Fig. 3c). It had four muscle strings: ventral right (VR), ventral left (VL), dorsal right (DR) and dorsal left (DL). Each string had 24 muscle cells arranged from head to tail (Fig. 3d). Tetrahedrons were controlled by their proximal muscle strings. The corresponding strings are visualized with different colors in Fig. 3e. We used a finite element method (FEM) solver to compute positions and velocities of all vertices on the deformable body at any given time. In the computation, the solver used 4,558 muscle constraints and 3,341 corotated elasticity constraints. Thus, our soft-body simulation engaged a sum of 7,899 mechanical constraints. After the geometry construction, we need to solve the body deformation efficiently. In our model, we selected a real-time, highly robust and accurate approach named projective dynamics as the FEM solver for calculation. The solved body state is shown in Fig. 3f.

We constructed a large 3D fluid simulation environment, where the body and food were embedded. This environment was essentially a large cube, with each edge equating to approximately 1,200 times the length of a C. elegans. The mechanic of the body movement in fluid is essentially a soft-body–fluid coupling problem. We used a mechanical model inspired by worm swimming, focused primarily on the thrust force (Fig. 3g) and drag force (Fig. 3h) on the body surface43. Gravity and buoyancy were assumed to be equal and cancel each other out, allowing the simulation of a much larger space and improved computational efficiency. To achieve forward locomotion behavior, we used projective dynamics to calculate real-time bending waves that propagated from head to tail. The interaction between these bending waves and the fluid generated impetus for forward locomotion (Fig. 3i).

C. elegans is an animal with soft body that exhibits special patterns during locomotion, wherein every point on its body oscillates continuously. Therefore, it is difficult to quantify the trajectory and body state during locomotion. Here, we proposed an effective and simple method to measure C. elegans locomotion. The main idea of this method is to establish a numerically stable coordinate system relative to the body itself, named Target Body Reference Coordinate System (TBRCS) (Fig. 4a). First, we defined the target body, standard body and Standard Body Coordinate System (SBCS). Then, we computed transformation M between the target body and the standard body. Finally, we used M to perform 3D transformation on the SBCS to obtain the TBRCS. Details of this method are described in Methods. Using this method, we can stably quantify not only the body’s locomotion trajectory (Fig. 4a) but also the body states including the relative position and velocities of any points on the C. elegans body (Fig. 4b,c) and steering angle (Fig. 4d). For example, Fig. 4e shows the relative positions of 17 sampled 3D tracking points, while Fig. 4f shows their corresponding velocities. In Fig. 4e, the swing direction of the body was the Z direction of the TBRCS (dorsal–ventral direction). Also, there was a spring movement in the X direction of the TBRCS (head–tail direction) during forward locomotion. Locomotion in the Y direction of the TBRCS (left–right direction) was nearly flat because muscle activations were approximately symmetric in this direction. Figure 4f shows that, in this case, the primary propulsion of forward locomotion originated from the tail (pink line), as faster swing generates more thrust force. Moreover, our method enables the quantification of the body’s steering. Figure 4d shows an example of a steering angle θ, which was defined as the angle between the TBRCS x axis and the direction of velocity. The steering angle θ was also numerically stable.

a, A schematic diagram of TBRCS to quantify behavior stably. The standard body and SBCS are depicted on the left. The target body and TBRCS are illustrated on the right. Matching points (magenta dots) are positioned on both the standard and target body. The magenta lines link the corresponding points on two body. The transformation matrix M is obtained through singular value decomposition, enabling the conversion from SBCS to TBRCS. The trajectory of the target body center (orange line) exhibits a zigzag pattern, whereas the trajectory of TBRCS (green line) is smooth. b, Tracking body movement with TBRCS. Seventeen tracking points were defined on the surface of both the standard body and the target body. The magenta lines represent relative positions, while the blue arrows indicate relative velocities. Coordinate systems of the head on standard body and target body are drawn out to display translation and rotation of the head on target body. c, Trajectories of 17 tracking points on the body. d, Steering angle θ of the body. The velocity vector is depicted as the yellow arrow, and the X, Y and Z axes of TBRCS are represented by red, green and blue arrows, respectively. θ is defined as the angle between the red arrow and the yellow arrow and remains stable over time. e,f, Relative positions (e) and velocities (f) of 17 tracking points on the body during the movement.

Source data

Replicating locomotion behavior of C. elegans

In our model, we successfully replicated the locomotion behavior of C. elegans by a closed-loop interaction between the neural network model and the body–environment model. Specifically, the neural network model sensed the dynamic food concentration in the environment by sensory neurons. This sensory information was used to calculate the membrane potentials of motor neurons. The membrane potentials of motor neurons were subsequently translated into muscle activation signals, which controlled the movement of the C. elegans body to navigate toward the food in the environment. An overview of this closed-loop simulation is shown in Fig. 5a. Notably, we observed that the trajectory of the C. elegans movement in our model was similar to the zigzag trajectory recorded in the experiments44 (Fig. 5b). In addition, C. elegans in both the simulations (Supplementary Videos 1 and 2) and experiments exhibited a realistic dorsoventral fluctuation during 3D movement45,46.

a, The information flow diagram of the closed-loop interaction between the neural network model and the body–environment model. b, A comparison of the C. elegans trajectory during forward locomotion in the simulation (left) and the experiment (right). c, The input current injected to sensory neurons during locomotion. d, Left: the neural network model of C. elegans. Right: the membrane potentials of all the motor neurons in the model during locomotion. e. Left: the body model with 96 muscle cells. Right: the activation signals of all muscle cells during locomotion. Panel b (right) reproduced with permission from ref. 44, Elsevier.

Source data

In our current configuration for sensation, the food concentration in the virtual environment followed a linear distribution. To incorporate this sensory information into our model, we used the derivative of the food concentration as the amplitude of an external current injected into the soma of all sensory neurons. For neuromuscular coupling, we used a linear transformation, treating the neural network model as a reservoir to generate muscle activities47 (Methods).

During locomotion, the input of sensory neurons exhibited fluctuations due to the zigzag movement of the body’s head (Fig. 5c). The membrane potentials of each individual motor neuron also oscillated in response to the sensory input, especially the head motor neurons (Fig. 5d). The activation of muscle cells revealed traveling waves from the head to the tail (Supplementary Fig. 4), accompanied by alternating contractions and relaxations of dorsal and ventral muscle cells (Fig. 5e). These findings resemble observations in biological experiments48.

To facilitate visualization, we have incorporated the locomotion of C. elegans, the activities of its neural network model, and muscle activities into our graphical user interface (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Impact of neural network structure on dynamics and behaviors

We are interested in exploring the extent to which network structure influences the neural dynamics and behaviors. Thus, we conducted synthetic perturbations on the structure of our neural network model. Synthetic perturbations of the neural system often exceed individual tolerance level in animals. However, our model enables researchers to carry out experiments without concerns about experimental technique limitations or animal tolerance. Based on BAAIWorm, we performed experiments involving synthetic perturbations to quantitatively examine the impact of network structure on network dynamics and behaviors. The experiments include removing neurites, shuffling synapse and gap junction locations, shuffling synapse weights, shuffling gap junction weights, removing synapses and removing gap junctions. For shuffling operations, different random seeds produce different results, whereas for other perturbations, simulation results are consistent. The results in Fig. 6 represent one of the trials (random seed 64). The results of multiple simulation with different seeds are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6a.

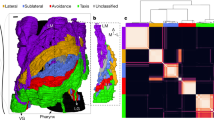

a, Column 1: a schematic diagram illustrating connections between two neurons in the neural network model. The ball and stick denote soma and neurite, respectively. The rectangles with solid and dashed lines indicate synapses and gap junctions. The rectangles with different colors represent different connections. The width of rectangles signifies connection weights. The depicted connections between this neuron pair represent all connections in the neural network model. Column 2: a Pearson correlation matrix of neurons during simulation of the neural network model. Column 3: locomotion behavior of the C. elegans body controlled by the neural network model in column 1. Columns 4 and 5: the relative position and velocity of 3D tracking points on the head (red), center (blue) and tail (green) of the C. elegans body during movement (Euclidean distance). n = 200, time step 0.1 s. Each point represents one relative velocity exported at each time step. These data are replicable using our code once the random seed is fixed, regardless of the number of replications. The bottom, middle and top lines of the box plot respectively indicate the 25th, 50th (median) and 75th percentiles. The whiskers extend to the minima and maxima within 1.5 times the range between the 25th and 75th percentiles from the bottom and top bounds of the box plot. Flier points are those past the end of the whiskers. b–g, Diagrams represented as in (a), but with different perturbation types: removal of neurites from all neurons in the neural network model, relocating connections onto the soma (b); shuffling the location of connections on neurites while fixing source and target neurons (c); shuffling the weights of synapses while fixing their locations (d); shuffling the weights of gap junctions while fixing their locations (e); removal of all synapses in the neural network model (f); and removal of all gap junctions in the neural network model (g). These perturbations are sequenced on the basis of their distance to the control group in terms of the Pearson correlation matrix (b: closest, g: farthest).

Source data

In all the perturbation scenarios, the body exhibits a higher degree of twisting during locomotion, as indicated by the larger relative locations of tracking points on the head and tail compared with the control group (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 6a–c). This suggests that neurites play crucial roles in the computations associated with network information processing. Moreover, shuffling connection locations within the model usually leads to faster oscillations of the body but slower forward locomotion, as indicated by larger relative velocities compared with the control group (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 6d–f). This suggests that the specific locations of connections along the neurites are important, potentially facilitating localized computations within neurons. In addition, despite that the neural network model contains fewer gap junctions than synapses, the role of gap junctions in the C. elegans neural network appears to be more important than that of synapses (Fig. 6d–g) because perturbations on gap junctions result in more obvious changes in the Pearson correlation matrix compared with perturbations on synapses. Removing gap junctions accelerates the twisting of the body compared with the control group, whereas removing synapses results in slower twisting (Fig. 6f,g and Supplementary Fig. 6d–f). These results emphasize the importance of network structure in shaping network dynamics and behavior patterns. By using our model, researchers can gain insights into the contributions of network structure to neural network.

Discussion

There exist many typical models simulating body dynamics and their interactions with the environment. For example, OpenSim49 aims to develop models of musculoskeletal structures and create dynamic simulations of movement in closed-loop style in three dimensions, but mainly for humans. There are many two-dimensional worm body models50,51 that elegantly simulate behaviors and provide insights into proprioception and the propagation of neuronal oscillations during worm locomotion. However, although more challenging, we believe that 3D body and physical environment simulations of C. elegans can more precisely replicate natural motion patterns such as twisting and postural changes45.

OpenWorm provides a platform for understanding the biology of C. elegans. BAAIWorm builds upon OpenWorm’s valuable tools and data, such as cell model morphology, synaptic dynamic and 3D worm body information, but presents several essential advancements over OpenWorm. First, our neural network model is highly detailed and trained to fit data at both neuron and network levels. Second, we used worm body and environment simulation methods supporting larger-scale and highly efficient simulations. In addition, we accomplished a closed-loop interaction with sensory feedback from the 3D environment. Details of comparisons are presented in Supplementary Table 5.

As we focused initially on where we have the most robust data and urgent needs, BAAIWorm includes several simplifications. For example, considering that several neurons in C. elegans cotransmit multiple neurotransmitters52,53, we did not strictly constrain the model with Dale’s law during the training process. BAAIWorm can be improved to more accurately reflect synaptic polarities as more experimental data become available. For sensation, we simplified that the food concentration gradient at the head was the sole input, which was transferred into current injected into all sensory neurons. In future work, the sensor can be designed to detect the absolute concentration rather than the gradient, and we will incorporate more complex sensory inputs and integrate multimodal sensory feedback, such as mechanical stimuli, temperature stimuli and body proprioception48, into the model. Moreover, we adopted a simple but more functional approach from prior studies47,54 (reservoir computation, for motor control) and we used matrix analysis (Supplementary Fig. 7) to ensure that many neurons contribute to the signaling of the muscles. In future iterations, we will use a more realistic model of the neuromuscular junction with specific ion channels such as calcium channels and incorporate muscle morphology, connection location and stretch forces to establish a more biophysically accurate model.

When the input of the neural network model was a periodic standard signal, that is, without sensory feedback from the environment, the membrane potentials of motor neurons and the activations of muscle cells were periodic (Supplementary Fig. 8). This resulted in the movement trajectory of the C. elegans body following a standard Z shape, which was extremely similar to the trajectory in the experiment44,55 (Supplementary Fig. 8b and Supplementary Video 3). Conversely, When the input was a sensory signal dependent on the body’s location in the environment (Fig. 5), the input was not periodic, leading to nonperiodic dynamics in both neurons and muscle cells. Therefore, the trajectory of the body was not as regular as that observed in the experiment (Fig. 5). Future studies will focus on designing more reasonable central pattern generators or motor control systems to achieve more realistic movement.

In our current model, we modeled 136 neurons rather than all 302 neurons, and the only behavior considered was zigzag locomotion. Training biophysically detailed neural network model is challenging and consumes much time and graphics processing unit memory resources. In the future, we will improve the optimization algorithm to effectively train larger detailed neural networks that contain all 302 neurons, with more constraints such as single-neuron voltages, and reproduce more behaviors beyond zigzag locomotion.

The neural network model of BAAIWorm integrated experimental data including ion channel dynamics, neural morphologies, electrophysiology, connectome, synaptic organization rules on neurites, and neural activities. Although we collected and integrated as much data as possible up until 2023, there remained a substantial amount of detail that could not be fully implemented due to a lack of data. Also, the physical parameters in the body–environment model did not correspond precisely to those of actual C. elegans because they were difficult to measure accurately. However, with the influx of new experimental data, these models can be enhanced and refined.

With ongoing experimental data and updates on BAAIWorm, it has the potential to enhance our computational technical capabilities to study C. elegans. For example, we can modulate ion channels or alter specific connections in our neural network model to investigate how experimental manipulations (for example, through genetic mutations or pharmacological interventions) may impact neural dynamics and behavior. Moreover, BAAIWorm enables us to test hypotheses that are currently challenging to verify experimentally. For example, some studies have found that different locations along the neurite of a C. elegans neuron may have distinct local neurite computations17,56. With BAAIWorm, we can precisely move the connection between two neurons or change the connection strengths. Feedback from the environment can help to investigate questions such as how the neural network adapts to environmental stimuli. These in silico experiments can guide the design and interpretation of electrophysiology, imaging and behavioral experiments.

Beyond its technical capabilities, BAAIWorm represents an advancement in multiscale computational modeling of biology. ‘Worm-As-a-Whole’ enables a variety of scientific discoveries that were previously unattainable. For instance, the platform has the potential to establish cause-and-effect relationships between genetic mutations and neuronal behaviors by enabling precise manipulation and observation of neural activity and its downstream effects. Furthermore, BAAIWorm facilitates the study of multiscale interactions, allowing researchers to explore the impact of molecular and cellular processes on larger network dynamics and behavior. This is critical for understanding system-wide functions57. In addition, while the current version of BAAIWorm does not model synaptic plasticity explicitly, its modular structure provides a foundation for future integration of plasticity mechanisms, potentially offering insights into adaptive neural reorganizations. These features make BAAIWorm a promising tool for advancing our understanding of neural dynamics across different biological scales.

BAAIWorm can also be used in computer science and other interdisciplinary fields. For example, it can be used to test and refine simulation methods, enhancing the accuracy of virtual representations. Moreover, in reinforcement learning, BAAIWorm’s closed-loop interactions present an ideal scenario for developing and testing algorithms in a biologically relevant context.

Methods

Details of the neural network model

Neuron models

Neurons were modeled by morphologically derived multicompartmental models with somatic Hodgkin–Huxley dynamics58 and passive neurites. These neuron models captured both the biophysical properties and the spatial complexity of neurons. The models integrated three kinds of neuron data: ion channel, morphology and electrophysiology.

Ion channel models were determined according to published studies33. There were 14 ion channels divided into 4 categories: voltage-gated potassium channels (SHK-1, EGL-36, SHL-1, KVS-1, KQT-3, EGL-2 and IRK1/3), calcium-regulated potassium channels (SLO1, SLO2 and KCNL), voltage-gated calcium channels (EGL19, UNC2 and CCA1) and passive sodium channel (NCA). Model equations and parameters for ion channels are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

For morphologies of neuron models, the spatial structures were adopted from the C. elegans neuronal anatomy models created by the Virtual Worm Project32 and the OpenWorm Project9. Each neuron model had a soma section and several neurite sections. Neurite sections were further divided into several compartments, each of which was shorter than 2 μm.

Only soma compartments had active ion currents. Soma compartments and neurite compartments shared the same passive properties. To identify the passive and active parameters that reproduce experimental data of voltage–current clamps, we initially used a deep learning tool59 that uses model-generated synthetic data to accurately and efficiently infer neural parameters. Then we manually fine-tuned these parameters. Parameters with extremely low values (<0.00001 nS μm−2) have negligible impact on the target dynamics. Therefore, they were manually set to 0 in simulation to simplify the model without influencing the model’s accuracy. The value of the parameters are presented in Supplementary Table 3.

We compared two features of the patch-clamp traces between experimental data and our single-neuron models, the voltage or current at steady state and the initial peak point (Supplementary Fig. 1). The steady state is where the membrane potential becomes steady. The initial peak point is identified as the first time its gradient decreased to a certain threshold (150 mV s−1) after the peak of the voltage or current gradient. Before identifying the initial peak point, the voltage or current gradient is smoothed using a Hamming filter to reduce the impact of experimental noise.

Less than 20% of the C. elegans neurons have been recorded for the desired electrophysiology data. To estimate model parameters for those neurons that were not recorded, a method was implemented to generalize parameter values. First, considering the available data and hierarchy of information flow in C. elegans nervous system15,27, the neurons were divided into five functional groups (sensory neuron, interneuron, command interneuron, head motor neuron and body motor neuron; Supplementary Table 4). Second, five neurons of each functional group (AWC35, AIY36, AVA37, RIM36 and VD5 (ref. 38)) were selected and their model parameters were optimized as described above. These parameter values of optimized neuron models were then generalized to other neuron models according to their functional categories. In other words, neuron models in the same functional group share identical electrical parameters. Each neuron model has its own morphologies, yet it has electrical properties similar to those of neurons in the same functional group.

The electrophysiology data in Supplementary Fig. 1 (gray traces) were collected from published papers. For the AIY (Liu et al.36, fig. 1a) and RIM (Liu et al.36, fig. 1a), the raw data were included as supplementary files in the original publications. However, for the AWC (Ramot et al.35, fig. 8b), AVA (Mellem et al.37, fig. 1d) and VD5 (Liu et al.38, fig. 8 (wild type)), the numerical data were not provided. Therefore, we extracted the numerical data from the figures using a digital image processing software (GetData Graph Digitizer). The extracted numerical traces are saved as data files in our GitHub respository (https://github.com/Jessie940611/BAAIWorm/tree/main/eworm/model_figure/single_neuron/electrophysiology_data).

Graded synapse and gap junction models

The neuron models were connected by graded synapses36,60 and gap junctions61 in the C. elegans neural network. Graded synapses, including excitatory and inhibitory synapses, were modeled according to published C. elegans models9,40,41. The synaptic conductance is continuously changed with the presynaptic membrane potential. The postsynaptic current is given by

where w is the maximal postsynaptic membrane conductance for the synapse, s is a voltage-sensitive parameter controlling the conductance, E is the reversal potential, τ is the time constant of s, Vth is the presynaptic equilibrium potential at the middle of the voltage-sensitive range and Vpre is the presynaptic membrane potential.

Gap junctions were modeled as simple resistances, where current flowing from presynaptic cell to postsynaptic cell is given by

where w is the conductance of gap junction.

The parameter values of these synapses were set according to published models61: the conductance of the synapses and gap junctions had the same order of magnitude (1 × 10−4 μS). The specific weight of each synaptic connection in a specific neural network can be optimized according to a target, as described in ‘Connection parameter optimization’ section.

Connection locations

Detailed neuron connections in the neural network model were located on the neuronal neurite (axons or dendrites) of the neurons, which were based on the neuron connectivity matrices and a neurite connectivity algorithm.

The neuron connectivity matrices were acquired from published connectome data15. The original data in the matrices were the total number of electron microscopy (EM) series of all synapses (or gap junctions) between two neurons. In our work, the number of EM series was transformed into the number of synapses (or gap junctions) by

where C is the number of EM series and a and b are constants. For synapses, (a=23.91) and (b=0.02285), while for gap junctions, (a=20.49) and (b=0.02184). These parameters were inferred from partial-animal connectome data15.

After the number of synapses (or gap junctions) was determined, the locations of synapses (or gap junction) on neural neurites were identified by a connection algorithm. The algorithm was based on the rule that distances between the centroid coordinates of possible presynaptic and postsynaptic neurites follow a certain statistical distribution17. We fit the synapse and gap junction distribution by two inverse Gaussian distributions

where μ = 0.44 and k = 0.63 for synapse distribution, and μ = 0.70 and k = 0.40 for gap junction distribution. The algorithm of generating connection locations is in Supplementary Algorithm.

C. elegans neural network model

Our neural network model consists of 136 neurons, including 15 sensory neurons for inputs and 80 motor neurons for outputs (Supplementary Table 6). We chose these neurons for the following reasons. First, 65 head ganglia neurons, whose neural dynamics were recorded in the published whole-brain Ca2+ imaging experiment24, should be selected to enable the comparison between experiment and simulation. Second, other 71 neurons, most of which were motor neurons in the locomotion circuit of C. elegans27,28, were added to the network so that the model could be complete in a sensory–motor functional structure. In summary, this model contained neurons for chemosensory, decision and locomotion.

In our multicompartment neural network, our single-neuron models are not isopotential. For example, in the AVAL neuron, depolarization from the soma attenuates as it travels along the axon (Supplementary Fig. 9). However, distal synapses receive inputs from other neurons, which helps to achieve sufficient depolarization. This design ensures that the model works well in the network.

Connection parameter optimization

The weights of synapses and gap junctions in the neural network were initialized randomly. The polarities of synapses were initialized randomly according to a given excitatory/inhibitory ratio (2.33). These parameters were optimized using an unpublished optimization algorithm for multicompartment neural network. The algorithm was adapted from our previous work62, which combined cable theory and gradient-descent methods. It used a mathematical approximation approach to calculate gradients for backpropagation through time to update parameters. Except for the weights (of synapses and gap junctions) and the polarities (of synapses), the inputs (of some sensory neurons) can be optimized. The self-contained and executable code of this optimization is available in our GitHub repository (https://github.com/Jessie940611/BAAIWorm/tree/main/eworm_learn).

PCA of neural activities

PCA was applied to the time series data of soma membrane potential of the 65 head neurons. Before conducting the analysis, the time series data were preprocessed by subtracting the mean value of the trace.

Correlation analysis

The correlation between two neurons was quantified by the Pearson correlation coefficient of their neural activities, which ranged from −1 to 1. A coefficient of −1 or 1 indicates a strong negative or positive correlation of neural activity, respectively. A coefficient of 0 indicates that the neural activities of the two neurons are unrelated. In this analysis, the neural activity was represented by the membrane potential of soma.

Simulation environment

The C. elegans neural network simulation and optimization were conducted with the code written in Python 3.8, and NEURON 8.0.0 was used as the simulation engine63. Experiments were performed primarily on a system configured with Ubuntu 18.04, an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 graphics processing unit, 16 GB random-access memory and an Intel Core i7-10700K central processing unit.

Details of the body–environment model

The body model

Tetrahedron is the simplest ordinary convex polyhedra in 3D space. It has four vertices and six edges and is bounded by four triangular faces. We used the tetrahedron as the basic element to construct the body model. The surface shape of the body was extracted as a triangle list from Sibernetic membrane data64. Then, we triangulated the body with a robust and high-quality algorithm65. The triangulated tetrahedron mesh was refined for the mechanics solver. The final body mesh was in a straight, natural resting pose that we defined as the standard body (Fig. 3a). The triangulated tetrahedron body was not strictly symmetric in the dorsal–ventral direction and the left–right direction. The triangulation algorithm had additional constraints on the quality of tetrahedrons. This nonstrict symmetry is probably more consistent with real C. elegans. The above-mentioned Sibernetic worm body data can be obtained from OpenWorm8 version ow-0.9.5. The triangulation algorithm of tetrahedron mesh can be obtained from TetWild65.

Muscles

Ninety-sixmuscles were arranged from head to tail according to the C. elegans anatomy. Each of the 24 muscles was grouped into a longitudinal string, marked as VR, VL, DR and DL in four quadrants (Fig. 3b)64. We imported the body membrane mesh into Blender and modeled VR, VL, DR and DL by four Bezier curves. Then, the muscle geometry was exported as a wavefront obj file. We used FEM to simulate the soft body and used finite element constraints to simulate elastic muscle cells of the body. Each muscle cell (Fig. 3a) corresponds to one or more FEM constraints according to the discretized tetrahedron body (Fig. 3c). Only nearby tetrahedrons can be driven by corresponding muscle cells.

Soft-body solver

We used projective dynamics66 as the solver of the soft body. The purpose of the mechanics solver is to calculate the positions and velocities of all 3D vertices of the deformed body over time. The key idea of projective dynamics is to compute a local step and a global step iteratively. At the local step, vertex positions of the body are fixed and projection variables are updated. At the global step, projections are fixed and vertex positions of the body are updated. The local step is well suited for parallelism and, thus, can be optimized for performance. The global step is a linear system and can be precomputed if the body geometry and constraints are not changed. After a few local–global iterations, the vertex positions of deformed body are converged. Then velocity of deformed body can be computed by Euler integration.

Interaction with environment

A simplified model of hydrodynamics was used to simulate the interaction between the body and the fluid, similarly to ref. 43. For simplicity, we supposed that external force is formed only at the surface of the body. Two kinds of external force were considered here: thrust force by body movement and drag force by fluid. With this simplification, computation in the whole 3D fluid environment is avoided. Thus, more agents, larger environments and more complex tasks are achievable through this simplification. SoftCon43 was used as the basis of the body–environment model.

Numerical stable coordinate system for body movement

C. elegans is a soft-body animal that has special patterns during movement. Every position of the body is oscillating during movement. Moreover, as there are no apparent important marks on the body during locomotion, it is hard to find a stable coordinate system for C. elegans movement. Simply using the head or body center as a coordinate system is not sufficient to analyze the body’s movement quantitatively and stably. Here, we proposed an effective and simple method to measure C. elegans locomotion. The core of our method is to find a numerically stable coordinate system relative to the body itself. The main steps of our method are as follows:

-

(1)

Define the target body, standard body and SBCS.

-

(2)

Obtain transformation between the target body and the standard body.

-

(3)

Use the transformation in step 2 to perform 3D transformation on the SBCS to obtain the TBRCS.

Details of the three steps are described below:

-

The target body is the research subject. It can change its shape over time and exhibits various behaviors. The standard body is a special case of the target body. Here, we define the standard body in a natural state where the head and tail are in a straight line, without stretching and bending. There is no internal force in the standard body soft body, and no external force acting on the standard body surface. The SBCS is a 3D orthogonal coordinate system used to reflect the overall structure and function of the standard body. In this case, we define the SBCS with origin at the standard body center. The X axis of the SBCS is toward the head of the standard body. The Z axis of the SBCS is toward the ventral–dorsal direction of the standard body. Three axes of the SBCS form a right-handed coordinate system. A schematic diagram of the target body, the standard body and the SBCS is shown in Fig. 4a.

-

In this step, we define the corresponding matching points on the target body and the standard body by using all the vertices of the body. The transformation between the matching points on the target body and the standard body is calculated as the transformation between the target body and the standard body. The calculation formulas of the transformation are as follows:

$$overline{{p}^{0}}=frac{1}{m}mathop{sum }limits_{i=1}^{m}{p}_{i}^{0}$$$$bar{p}=frac{1}{m}mathop{sum }limits_{i=1}^{m}{p}_{i}$$$${q}_{i}^{0}={p}_{i}^{0}-overline{{p}^{0}}$$$${q}_{i}={p}_{i}-bar{p}$$$$H={q}_{i}^{0}{{q}_{i}}^{{mathrm{T}}}$$$$R=V{U}^{{mathrm{T}}}$$$$T=bar{p}-Roverline{{p}^{0}}$$$$M=left[begin{array}{cc}R & T 0 & 1end{array}right].$$The matching points are represented by column vectors. ({p}_{i}^{0}) is matching points on the standard body, and pi is matching points on the target body. m is the number of matching points. (overline{{p}^{0}}) is the center point of matching points on the standard body, and (overline{p}) is the center point of matching points on the standard body. ({q}_{i}^{0}) refers to the standard body matching points with the center offset subtracted, and qi denotes the standard body matching points with the center offset subtracted. H is a matrix computed by ({q}_{i}^{0}{{q}_{i}}^{{mathrm{T}}}). ({{q}_{i}}^{{mathrm{T}}}) is the transpose of qi, ({q}_{i}=left[{q}_{1},{q}_{2}ldots {q}_{m}right]), ({q}_{i}^{0}=left[{q}_{1}^{0},{q}_{2}^{0}ldots {q}_{m}^{0}right]). U and V are obtained by the singular value decomposition (H=ULambda V) of the matrix H. UT is the transpose of U. M is the transformation matrix between the target body and the standard body, which will be used in the next step. R is the rotation part of M, and T is the translation part of M. A schematic diagram of matching points and transformation M is shown in Fig. 4a.

-

In this step, we use matrix M to perform 3D transformation on the SBCS to obtain the TBRCS. The matrix of the TBRCS can be formulated as (widehat{M}=M{M}^{0}=left[begin{array}{cc}R{R}^{0} & R{T}^{,0}+T 0 & 1end{array}right]). (M=left[begin{array}{cc}R & T 0 & 1end{array}right]). ({M}^{0}=left[begin{array}{cc}{R}^{0} & {T}^{,0} 0 & 1end{array}right]) is a matrix used to represent the SBCS. T0 is the origin of the SBCS, and R0 indicates orientation of the SBCS. The column vector of R0 represents the orthogonal coordinate axis. Finally, weobtain the TBRCS through (widehat{M}): (R{T}^{,0}+T) as the origin and ({{RR}}^{0}) as the orthogonal coordinate axis.

Numerically stable measurements of body movement

Measurement of body trajectory

During behavior analysis, C. elegans can be seen as a deformable biology composed of multiple points. When studying the locomotion of a deformable body, generally one or more points of the biology body is defined as a tracking object, and locomotion of the deformable body is studied through tracking these defined points. For deformable biology bodies such as C. elegans, the position and the velocity of local tracking points do not reflect well the overall state of body locomotion (Fig. 4c). As a result, values such as body trajectory or steering angle obtained through these tracking points are usually unstable over time. Using the TBRCS, we can better describe the overall trend of body movement. A comparison of trajectories is shown in Fig. 4a. If the center point of the body is used as the trajectory, the trajectory has a zigzag shape. However, if the TBRCS is used as the trajectory of body movement, the trajectory is a smooth curve, which means that it has stable values. These results indicate that the TBRCS is suitable as a measurement of overall path and direction of body locomotion.

Tracking body movement

Here, we demonstrate how to track body movement with the TBRCS. If the standard body is drawn in the TBRCS, then it can be used as a reference for the target body. The standard body and the target body are centrally aligned, translated and rotated together. We define ({s}_{k}^{0}) as 3D tracking points of the standard body and sk as 3D tracking points of the target body (k = 1, 2, &hellips;, n). n is the number of tracking points. The relative movement of the body can be defined as ({s}_{k}-{s}_{k}^{0}). It is a measurement of body locomotion relative to itself (the standard body), which is more numerically stable than relative to the environment. ({s}_{k}-{s}_{k}^{0}) is also a better calculation than that relative to the body center, since both the translation part and the rotation part of the whole deformation body are considered in the TBRCS. Moreover, the sampling bias of tracking points is eliminated through subtraction, since bias minus bias equals zero.

In Fig. 4b, we sampled 17 tracking points on the body uniformly. The offset of the tracking points is indicated by the pink lines between the tracking points. The relative velocity of 3D tracking points is indicated with blue arrows. As a common method, trajectories of sampled 17 tracking points that relate to world are also shown in Fig. 4c. We can see that, compared with all 17 tracking points trajectories, the trajectory of the TBRCS is the smoothest. The relative position and the relative velocity of 3D tracking points over time are plotted in Fig. 4e,f. In Fig. 4e, the positions of the 3D tracking points are tiled from bottom to top for clear seeing. In this case, the swing direction (Z direction of the TBRCS) of the swimming body can be clearly shown with the TBRCS. We also find that there is a spring movement in the X direction of the TBRCS (tail to head) during forward swimming. The locomotion in the Y direction of the TBRCS is nearly flat because muscle activations are approximately symmetrical in this direction. From Fig. 4f we can further deduce that the biggest propulsion of forward swimming comes from the tail (pink line), as faster swing generates more thrust force.

Steering angle of body movement

If ({O}_{{t}_{i}}) is the trajectory of TBRCS origin at time ti, ({t}_{i}={t}_{1},{t}_{2}ldots {t}_{m}), then we can calculate the velocity of TBRCS by ({v}_{i}=frac{{O}_{{t}_{i}}-{O}_{{t}_{i-1}}}{{t}_{i}-{t}_{i-1}}). In this way, velocity magnitude and velocity direction over time are numerically stable. We used angle θ, which is between the TBRCS X axis and vi as a measurement of steering, as shown in Fig. 4d. Both vi and the TBRCS are numerically stable over time; thus, θ is also numerically stable.

Locomotion behavior simulation of C. elegans

Simulation configuration

The neural network simulation was coupled with the physical body–environment simulation to achieve closed-loop interaction. Food was at the center of the simulated physical environment, acting as an attractor to C. elegans. The food concentration was linearly distributed in the environment. The neural system received currents regarded as sensory signals. The amplitude of the currents was proportional to the gradient of food concentration. We assumed that all sensors were located at the head of C. elegans and that the injected currents of all sensory neurons were the same (the gradient at the tracking point at the head of the C. elegans body). The outputs of the neural network controlled the movements of the body in the environment through a reservoir readout weight matrix. As the body moved in the physical environment, the distance between the body and the food changed, causing the food concentration gradient changed, which was transformed into currents injected into the soma of sensory neurons.

During the interaction of the two submodels, the simulation time step of the neural network was 5/3 ms and that of the physical environment simulation was 100 ms. The two systems synchronized every 100 ms to update the sensory signals and muscle forces.

Reservoir configuration

To establish the neuron–muscle connection between the neural system and physical body muscles, a reservoir computing framework was used. The neural network model acted as the nonlinear reservoir. The membrane potentials of 80 motor neurons were linearly combined and mapped to 96 muscle forces via an 80-by-96 matrix.

The reservoir was trained using data extracted from a 10 s movement generated in the simulated physical environment. The pairs of food concentration and muscle force during the movements were used as inputs to the neural network and target outputs of the readout layer, respectively. Only the reservoir readout matrix was optimized, whereas the parameters in the neural network model were fixed.

User-friendly interfaces

For simulation configuration, the neural network model consists of ion channel, neuron and network connection modules. The parameter and algorithm settings of each module can be modified independently. Parameters were saved in JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) files that are easy to read and modify.

For quantification, membrane potential of neurons, worm body data outputs, such as positions, velocities and trajectories of tracking points (Fig. 4), and muscle signals (Supplementary Fig. 5) can be exported seamlessly with our latest code (https://github.com/Jessie940611/BAAIWorm/blob/main/eworm/ghost_in_mesh_sim/worm_in_env.py). Tracking points, including the head, center and tail of the worm body, are configurable within the model. Future updates will include 3D tetrahedron analysis algorithms and an extended Worm tracker Commons Object Notation (WCON)67 file format for the worm’s 3D structure.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available in this Resource and Supplementary Information. These data are also available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13951773 (ref. 68) and GitHub at https://github.com/Jessie940611/BAAIWorm.

Code availability

The code is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13943857 (ref. 69) and GitHub at https://github.com/Jessie940611/BAAIWorm.

References

-

Ramaswamy, S. Data-driven multiscale computational models of cortical and subcortical regions. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 85, 102842 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Ramaswamy, S., Colangelo, C. & Markram, H. Data-driven modeling of cholinergic modulation of neural microcircuits: bridging neurons, synapses and network activity. Front. Neural Circuits 12, 77 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Billeh, Y. N. et al. Systematic integration of structural and functional data into multi-scale models of mouse primary visual cortex. Neuron 106, 388–403. e318 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Hjorth, J. J. et al. The microcircuits of striatum in silico. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9554–9565 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Markram, H. et al. Reconstruction and simulation of neocortical microcircuitry. Cell 163, 456–492 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Lobato-Rios, V. et al. NeuroMechFly, a neuromechanical model of adult Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Methods 19, 620–627 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Merel, J. et al. Deep neuroethology of a virtual rodent. In Proc. 8th International Conference on Learning Representations 11686–11705 (ICLR, 2020).

-

Sarma, G. P. et al. OpenWorm: overview and recent advances in integrative biological simulation of Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20170382 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Gleeson, P., Lung, D., Grosu, R., Hasani, R. & Larson, S. D. c302: a multiscale framework for modelling the nervous system of Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20170379 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Palyanov, A. Y. & Khayrulin, S. S. Sibernetic: a software complex based on the PCI SPH algorithm aimed at simulation problems in biomechanics. Russ. J. Genet. Appl. Res. 5, 635–641 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Urai, A. E., Doiron, B., Leifer, A. M. & Churchland, A. K. Large-scale neural recordings call for new insights to link brain and behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 11–19 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Zador, A. et al. Catalyzing next-generation artificial intelligence through NeuroAI. Nat. Commun. 14, 1597 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Roth, E., Sponberg, S. & Cowan, N. J. A comparative approach to closed-loop computation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 25, 54–62 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

White, J. G., Southgate, E., Thomson, J. N. & Brenner, S. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 314, 1–340 (1986).

Google Scholar

-

Cook, S. J. et al. Whole-animal connectomes of both Caenorhabditis elegans sexes. Nature 571, 63–71 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Witvliet, D. et al. Connectomes across development reveal principles of brain maturation. Nature 596, 257–261 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Ruach, R., Ratner, N., Emmons, S. W. & Zaslaver, A. The synaptic organization in the Caenorhabditis elegans neural network suggests significant local compartmentalized computations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2201699120 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Brittin, C. A., Cook, S. J., Hall, D. H., Emmons, S. W. & Cohen, N. A multi-scale brain map derived from whole-brain volumetric reconstructions. Nature 591, 105–110 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Venkatachalam, V. et al. Pan-neuronal imaging in roaming Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E1082–E1088 (2016).

Google Scholar

-

Li, H. et al. Fast whole‐body motor neuron calcium imaging of freely moving Caenorhabditis elegans without coverslip pressed. Cytometry Part A 99, 1143–1157 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Kato, S. et al. Global brain dynamics embed the motor command sequence of Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell 163, 656–669 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Randi, F., Sharma, A. K., Dvali, S. & Leifer, A. M. Neural signal propagation atlas of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 623, 406–414 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Bergs, A. C. et al. All-optical closed-loop voltage clamp for precise control of muscles and neurons in live animals. Nat. Commun. 14, 1939 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Uzel, K., Kato, S. & Zimmer, M. A set of hub neurons and non-local connectivity features support global brain dynamics in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 32, 3443–3459 (2022).

Google Scholar

-

Bargmann, C. I. Genetic and cellular analysis of behavior in C. elegans. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 47–71 (1993).

Google Scholar

-

Rankin, C. H. From gene to identified neuron to behaviour in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 622–630 (2002).

Google Scholar

-

Gray, J. M., Hill, J. J. & Bargmann, C. I. A circuit for navigation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 3184–3191 (2005).

Google Scholar

-

Chalasani, S. H. et al. Dissecting a circuit for olfactory behaviour in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 450, 63–70 (2007).

Google Scholar

-

Larsch, J. et al. A circuit for gradient climbing in C. elegans chemotaxis. Cell Rep. 12, 1748–1760 (2015).

Google Scholar

-

Bargmann, C. I., Hartwieg, E. & Horvitz, H. R. Odorant-selective genes and neurons mediate olfaction in C. elegans. Cell 74, 515–527 (1993).

Google Scholar

-

Piggott, B. J., Liu, J., Feng, Z., Wescott, S. A. & Xu, X. S. The neural circuits and synaptic mechanisms underlying motor initiation in C. elegans. Cell 147, 922–933 (2011).

Google Scholar

-

Grove, C. & Sternberg, P. in 18th International C. elegans Meeting (GSA, 2011).

-

Nicoletti, M. et al. Biophysical modeling of C. elegans neurons: single ion currents and whole-cell dynamics of AWCon and RMD. PLoS ONE 14, e0218738 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Sheng, K. et al. Domain adaptive neural inference for neurons, microcircuits and networks. Preprint at bioRxiv https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.10.03.510694v1 (2022).

-

Ramot, D., MacInnis, B. L. & Goodman, M. B. Bidirectional temperature-sensing by a single thermosensory neuron in C. elegans. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 908–915 (2008).

Google Scholar

-

Liu, Q., Kidd, P. B., Dobosiewicz, M. & Bargmann, C. I. C. elegans AWA olfactory neurons fire calcium-mediated all-or-none action potentials. Cell 175, 57–70.e17 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Mellem, J. E., Brockie, P. J., Madsen, D. M. & Maricq, A. V. Action potentials contribute to neuronal signaling in C. elegans. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 865–867 (2008).

Google Scholar

-

Liu, P., Chen, B. & Wang, Z.-W. SLO-2 potassium channel is an important regulator of neurotransmitter release in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Commun. 5, 5155 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Mainen, Z. F. & Sejnowski, T. J. Influence of dendritic structure on firing pattern in model neocortical neurons. Nature 382, 363 (1996).

Google Scholar

-

Wicks, S. R., Roehrig, C. J. & Rankin, C. H. A dynamic network simulation of the nematode tap withdrawal circuit: predictions concerning synaptic function using behavioral criteria. J. Neurosci. 16, 4017–4031 (1996).

Google Scholar

-

Prinz, A. A., Bucher, D. & Marder, E. Similar network activity from disparate circuit parameters. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 1345–1352 (2004).

Google Scholar

-

Sakata, K. & Shingai, R. Neural network model to generate head swing in locomotion of Caenorhabditis elegans. Netw., Comput. Neural Syst. 15, 199 (2004).

Google Scholar

-

Min, S., Won, J., Lee, S., Park, J. & Lee, J. Softcon: simulation and control of soft-bodied animals with biomimetic actuators. ACM Trans. Graph. 38, 1–12 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Sznitman, J., Purohit, P. K., Krajacic, P., Lamitina, T. & Arratia, P. E. Material properties of Caenorhabditis elegans swimming at low reynolds number. Biophys. J. 98, 617–626 (2010).

Google Scholar

-

Bilbao, A., Patel, A. K., Rahman, M., Vanapalli, S. A. & Blawzdziewicz, J. Roll maneuvers are essential for active reorientation of Caenorhabditis elegans in 3D media. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E3616–E3625 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Salfelder, F. et al. Markerless 3D spatio-temporal reconstruction of microscopic swimmers from video. In 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition 1965–1972 (IEEE, 2020).

-

Bhovad, P. & Li, S. Physical reservoir computing with origami and its application to robotic crawling. Sci. Rep. 11, 13002 (2021).

Google Scholar

-

Wen, Q. et al. Proprioceptive coupling within motor neurons drives C. elegans forward locomotion. Neuron 76, 750–761 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Delp, S. L. et al. OpenSim: open-source software to create and analyze dynamic simulations of movement. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 54, 1940–1950 (2007).

Google Scholar

-

Boyle, J. H., Berri, S. & Cohen, N. Gait modulation in C. elegans: an integrated neuromechanical model. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 6, 10 (2012).

Google Scholar

-

Izquierdo, E. J. & Beer, R. D. From head to tail: a neuromechanical model of forward locomotion in Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20170374 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Wang, C. et al. A neurotransmitter atlas of the nervous system of C. elegans males and hermaphrodites. eLife 13, RP95402 (2024).

Google Scholar

-

Serrano-Saiz, E. et al. A neurotransmitter atlas of the Caenorhabditis elegans male nervous system reveals sexually dimorphic neurotransmitter usage. Genetics 206, 1251–1269 (2017).

Google Scholar

-

Horii, Y. et al. Physical reservoir computing in a soft swimming robot. In ALIFE 2021: The 2021 Conference on Artificial Life (MIT Press, 2021).

-

Kwon, N., Pyo, J., Lee, S.-J. & Je, J. H. 3-D worm tracker for freely moving C. elegans. PLoS ONE 8, e57484 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Donato, A., Kagias, K., Zhang, Y. & Hilliard, M. A. Neuronal sub-compartmentalization: a strategy to optimize neuronal function. Biol. Rev. 94, 1023–1037 (2019).

Google Scholar

-

Bargmann, C. I. & Marder, E. From the connectome to brain function. Nat. Methods 10, 483–490 (2013).

Google Scholar

-

Hodgkin, A. L. & Huxley, A. F. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J. Physiol. 117, 500–544 (1952).

Google Scholar

-

Sheng, K. et al. Distilling multi-scale neural mechanisms from diverse unlabeled experimental data using deep domain-adaptive inference framework. Preprint at bioRxiv https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.10.03.510694v2 (2023).

-

Liu, Q., Hollopeter, G. & Jorgensen, E. M. Graded synaptic transmission at the Caenorhabditis elegans neuromuscular junction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 10823–10828 (2009).

Google Scholar

-

Shui, Y., Liu, P., Zhan, H., Chen, B. & Wang, Z.-W. Molecular basis of junctional current rectification at an electrical synapse. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb3076 (2020).

Google Scholar

-

Zhang, Y. et al. A GPU-based computational framework that bridges neuron simulation and artificial intelligence. Nat. Commun. 14, 5798 (2023).

Google Scholar

-

Hines, M. L. & Carnevale, N. T. The NEURON simulation environment. Neural Comput. 9, 1179–1209 (1997).

Google Scholar

-

Palyanov, A., Khayrulin, S. & Larson, S. D. Three-dimensional simulation of the Caenorhabditis elegans body and muscle cells in liquid and gel environments for behavioural analysis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20170376 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Hu, Y. et al. Tetrahedral meshing in the wild. ACM Trans. Graph. 37, 1–14 (2018).

-

Bouaziz, S., Martin, S., Liu, T., Kavan, L. & Pauly, M. Projective dynamics: fusing constraint projections for fast simulation. ACM Trans. Graph. 33, 1–11 (2014).

Google Scholar

-

Javer, A. et al. An open-source platform for analyzing and sharing worm-behavior data. Nat. Methods 15, 645–646 (2018).

Google Scholar

-

Mengdi, Z. et al. Data for an integrative data-driven model simulating C. elegans brain, body and environment interactions. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13951773 (2024).

-

Mengdi, Z. et al. An integrative data-driven model simulating C. elegans brain, body and environment interactions. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13943857 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the by Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence (BAAI). We thank X. Wu and B. Lei from BAAI for discussions. We thank Y. Wang from BAAI for writing the Application Programming Interface (API) of closed-loop interaction.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Z. developed the neural network model module, designed and conducted experiments, and interpreted results. N.W. developed the body–environment module. H.M. and L.M. developed the 3D neural visualization software. X.J. and M.Z. collected experimental data for constructing the neural network model. X.M. and M.Z. optimized the connection algorithm and rewrote the code of the neural network model module for open source. G.H. developed the optimization algorithm for the multicompartment neural network model. M.Z., N.W., X.J. and L.M. wrote the Resource. T.H. and K.D. reviewed the research and provided advice. L.M. and T.H. supervised the research, coordinated and conceptualized the study, and contributed to writing the Resource. All authors participated in the paper revision process.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Computational Science thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Ananya Rastogi, in collaboration with the Nature Computational Science team. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–6, Figs. 1–9 and algorithm.

Reporting Summary

Peer Review File

Supplementary Video 1

Closed-loop 3D simulation of C. elegans locomotion behavior.

Supplementary Video 2

Closed-loop 3D simulation of six C. elegans locomotion behavior.

Supplementary Video 3

Open-loop 3D simulation of C. elegans locomotion behavior.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, M., Wang, N., Jiang, X. et al. An integrative data-driven model simulating C. elegans brain, body and environment interactions.

Nat Comput Sci 4, 978–990 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-024-00738-w

-

Received: 10 March 2024

-

Accepted: 05 November 2024

-

Published: 16 December 2024

-

Issue Date: December 2024

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-024-00738-w