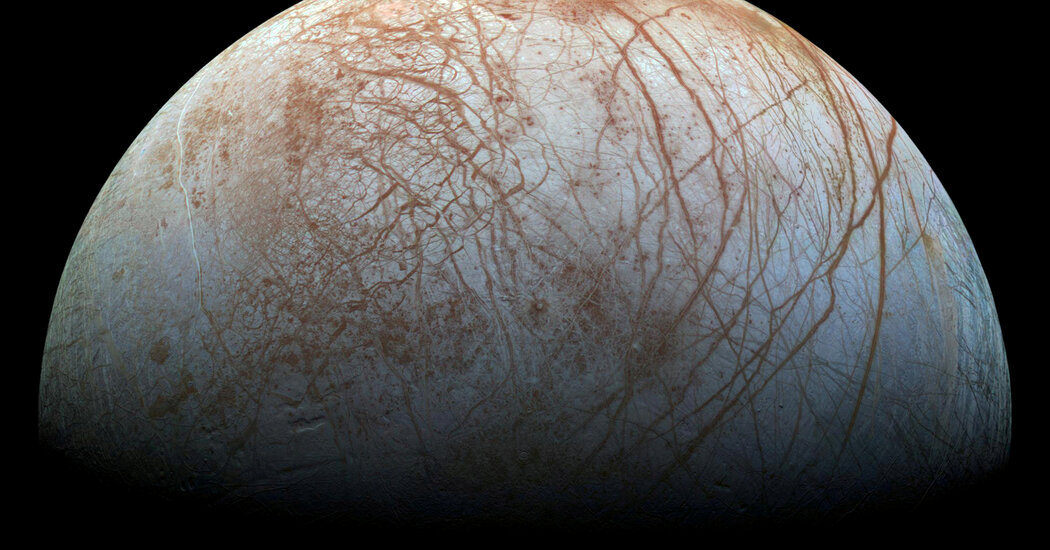

Under its bright, frosty shell, Jupiter’s moon Europa is thought to harbor a salty ocean, making it a world that might be one of the most habitable places in our solar system.

But most life as we know it needs oxygen. And it’s an open question whether Europa’s ocean has it.

Now, astronomers have nailed down how much of the molecule gets made at the icy moon’s surface, which could be a source of oxygen for the waters below. Using data from NASA’s Juno mission, the results, published on Monday in the journal Nature Astronomy, suggest that the frozen world generates less oxygen than some astronomers may have hoped for.

“It’s on the lower end of what we would expect,” said Jamey Szalay, a plasma physicist at Princeton University who led the study. But “it’s not totally prohibitive” for habitability, he added.

On Earth, the photosynthesis of plants, plankton and bacteria pump oxygen into the atmosphere. But the process works differently on Europa. Charged particles from space bombard the moon’s icy crust, breaking down frozen water into hydrogen and oxygen molecules.

“The ice shell is like Europa’s lung,” Dr. Szalay said. “The surface — which is the same surface that protects the ocean underneath from harmful radiation — is, in a sense, breathing.”

Astronomers speculate that this oxygen might move into Europa’s watery underworld. If so, it could mix with volcanic material from the seafloor, creating “a chemical soup that may end up making life,” said Fran Bagenal, a planetary scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Want all of The Times? Subscribe.