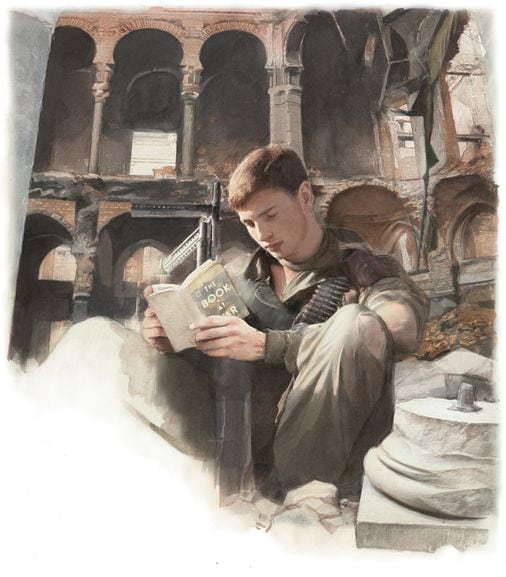

One might expect a book called “The Book at War” to focus on literature about combat, both for and against, but mostly against. Think “The Red Badge of Courage” (Stephen Crane, 1895), “All Quiet on the Western Front” (Erich Maria Remarque, 1929), “Catch-22″ (Joseph Heller, 1961), or other novels that highlight the absurdity and inhumanity of combat. Andrew Pettegree’s new study touches on such themes, but his more passionate interests lie elsewhere. Several different elsewheres, actually.

This is a big, eclectic, eccentric, and discursive book that isn’t just about specific books but also maps, military history and training, libraries, propaganda, and, most important, the battle of ideas. It is very Eurocentric, which makes a fair amount of sense; the defining wars that overlap with the history of book publishing were fought largely in Europe, and the author, a professor of history at the University of St. Andrews, is a British historian who has previously written about the history of libraries and the early impact of the printing press. Pettegree is at least as interested in form as content.

He’s also more interested in figures like Helmuth von Moltke, chief of the Prussian general staff and esteemed military theorist, than the general reader might be. Von Moltke is credited with pushing army field strategy in a more modern direction. If this kind of thing — and there is a lot of it here — isn’t what brought you to this particular party, have no fear. “The Book at War” is nothing if not wide-ranging, with subjects including wartime reading habits (at the front and at home), map-making (“War is good for cartography,” Pettegree tells us, before spending a chapter on the subject), and censorship, particularly during the Cold War, a period that provides some of Pettegree’s most fertile analytical ground.

For instance, did you know the CIA has been a major player in the publishing industry? When American publishers set their sights on breaking into European markets after World War II, the Agency was there to “steer” books that supported democracy into distribution on the continent. The CIA also had a major hand in publishing Encounter, a popular postwar journal of ideas which, as Pettegree writes, “soon established a solid position in the intellectual framework of British cultural life.” Eventually the CIA’s involvement was discovered, leading to some embarrassing moments. As the author writes, “When seventeen leading Anglo-American intellectuals published in Partisan Review an editorial denouncing CIA journals, presumably they were unaware that Partisan Review had itself received funds from CIA front organisations.” Oops.

If such discussion seems to veer afield from the book at war, that’s part of the book’s unlikely charm. For Pettegree, the idea of “the book” is really a container for larger concepts, which, when you stop and think, is a good working definition for what a book is. The author takes advantage of the fact that books encompass just about every facet of life to riff on other subjects, not the least of which is battle.

Paradoxically, while matters of war provide grist for countless volumes, war itself can be quite damaging to books as physical objects. Pettegree provocatively asks if this is always a bad thing: “Should we lament the loss of the 9 million copies of Hitler’s Mein Kampf circulating in Germany by 1945, or the 100 million copies of Mao’s Little Red Book destroyed when his cult receded?” Indeed, as he points out, the Nazis were quick to burn or otherwise destroy books they deemed harmful to their conception of racial and ideological purity. Pettegree understands that books are generally not just books. They are, to quote the title of his introduction, “Weapons in the War of Ideas.” Any of the censorious reactionaries currently hard at work banning books to which they object would certainly agree.

Pettegree moves closer to home when he shifts into what we might consider literary or cultural criticism, addressing anti-slavery books that influenced or at least buttressed the Union cause in the Civil War, including Frederick Douglass’ “Narrative of the Life” and “My Bondage and My Freedom,” Solomon Northrup’s “Twelve Years a Slave,” and especially Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” Here Pettegree’s outsider status lends a degree of perceptive distance: “These books provided a more powerful distillation of the great moral issue dividing America than the myriad pamphlets and shifty legal compromises that had characterised this unsettled period of American history.”

For the most part, however, “The Book at War” is content to march along lesser-worn paths. A more accurate title might be “Knowledge at War,” for Pettegree’s interests go beyond what is generally held between two covers. This is a long, loping read, a campaign to reveal functions of reading that we often take for granted. The results are expansive, rather than reductive, and well worth the fight, as long as you’re willing to learn a little about Prussian history along the way.

THE BOOK AT WAR: How Reading Shaped Conflict and Conflict Shaped Reading

By Andrew Pettegree

Basic Books, 480 pages, $35

Chris Vognar, a freelance culture writer, was the 2009 Nieman Arts and Culture Fellow at Harvard University.