As the global community grapples with the urgent need to mitigate climate change, nature-based solutions have emerged as a promising strategy for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and enhancing climate resilience. Recent studies suggest that natural climate solutions are modelled to potentially provide 37% of cost-effective CO2 mitigation needed through 2030 for a 66% chance of holding warming to below 2C. Despite this potential, the implementation of nature-based solutions faces significant challenges, particularly in financing, governance, and integration into broader climate policies.

—

Nature-based solutions are defined as measures that protect, conserve, restore, and manage ecosystems while also enhancing human well-being, ecosystem services, and biodiversity. The core principle behind nature-based solutions is to work in harmony with nature rather than against it, offering sustainable and cost-effective alternatives to conventional engineering solutions.

Examples of nature-based solutions can be seen in Kenya, where drought is a persistent threat, and rangeland restoration efforts have significantly improved livestock productivity. These restored rangelands provide both resilient grazing grounds for livestock and additional income streams through sustainable practices like rotational grazing and fodder production, helping communities against the economic shocks that often accompany prolonged dry periods, thereby enhancing their overall resilience to climate change. Similarly, in Zimbabwe, forest conservation efforts have helped maintain the ecosystems necessary for beekeeping, a key source of income for local communities during droughts when traditional crops fail, ensuring that bees have access to diverse flora.

Beyond their role in climate mitigation, nature-based solutions offer a range of co-benefits that are crucial for sustainable development. They have demonstrated significant positive impacts on biodiversity, thereby supporting a variety of plant and animal species. On average, nature-based interventions were associated with a 67% increase in plant or animal species richness, with 88% of interventions that reported positive outcomes for climate change adaptation reporting benefits for ecosystem health. Nature-based solutions also play a significant role in improving water quality. They can filter pollutants from runoff, improving the quality of water in rivers, lakes, and coastal areas, benefiting ecosystems, human health and livelihoods. Additionally, by involving local communities, these projects have social and economic benefits, such as job creation and increased environmental stewardship.

Nature-Based vs Engineering-Based Solutions

To date, the predominant response to extreme weather events and natural disasters has been engineered interventions like seawalls and levees. In Bangladesh, for example, 88% of adaptation projects approved by the Bangladesh Climate Change Trust involved engineered solutions, with only 12% focusing on nature-based solutions. Traditional engineering methods are often more effective in providing immediate, localised, and robust protection by physically blocking or redirecting water and other natural forces. However, they tend to be rigid, expensive to build and maintain, and can sometimes exacerbate environmental problems by disrupting natural ecosystems and processes.

Nature-based solutions come with challenges, too. They require more space and time to establish and may not be as immediately effective as traditional methods in certain high-risk areas. Moreover, the success of nature-based solutions depends on proper planning, community involvement, and long-term management to ensure that they deliver the intended benefits. However, there is increasing evidence that these solutions can complement or even replace traditional engineering-based solutions in certain contexts. A 2024 paper suggests that, among the studies that compared nature-based solutions with engineering-based approaches, 65% found nature-based solutions to be more effective at mitigating hazards, while 26% found them to be partially more effective, but never less effective.

How Cost-Effective Are Nature-Based Solutions?

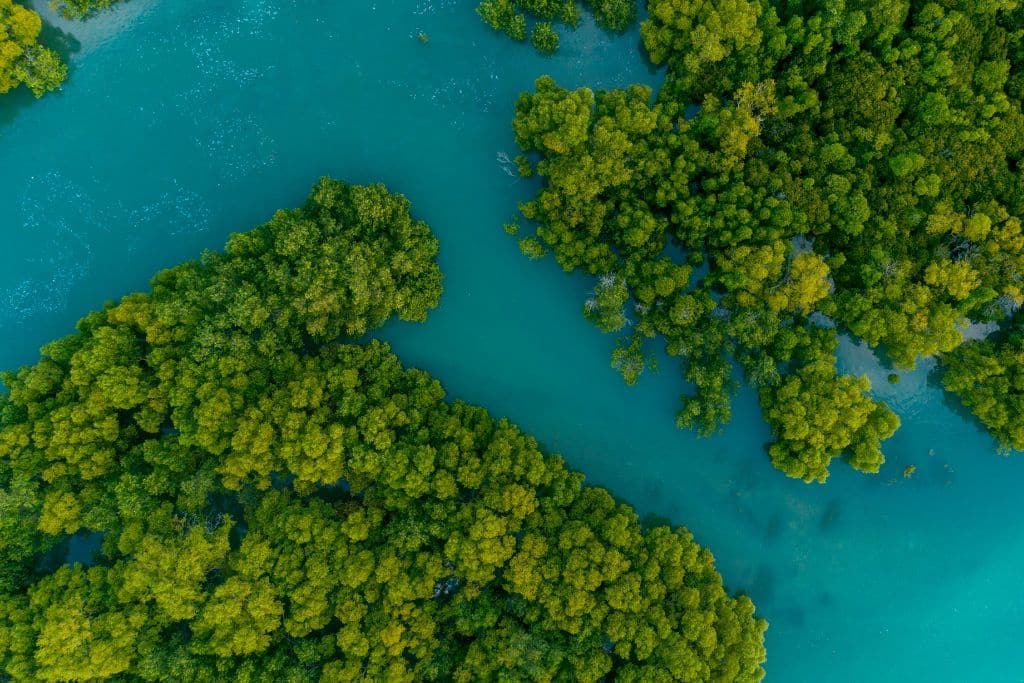

In a 2024 study conducted by researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, nature-based solutions were found to be consistently cost-effective in addressing a wide range of natural hazards. The study reviewed over 20,000 scientific articles and found that 71% of studies concluded that nature-based solutions are a cost-effective approach to mitigating risks from disasters such as floods, hurricanes, heatwaves, and landslides. Additionally, another 24% of the studies found nature-based solutions to be cost-effective under certain conditions. The most effective ecosystem-based approaches for mitigating natural hazards were linked to mangroves (80%), forests (77%), and coastal ecosystems (73%).

The problem with current evidence for the cost-effectiveness of nature-based solutions is that quantifying the full range of advantages they provide poses significant challenges, leading to an underestimation of their long-term economic benefits. These solutions offer a wide range of non-market benefits, including food and water security, carbon sequestration, aesthetic enjoyment, and community cohesion. These benefits are rarely accounted for in economic evaluations due to monetisation difficulties and uncertainties about their non-market value. Additionally, estimating the cost-effectiveness of nature-based solutions is complicated by the variable levels of protection they offer. It can fluctuate based on the intensity and frequency of threats, the resilience of the ecosystem to climate change, and the vulnerabilities of the socioeconomic system.

Consequently, predicting and estimating the costs of ecosystem responses is more challenging compared to engineered infrastructure. As a result, even though nature-based solutions offer long-term economic and environmental benefits, they are often underutilised in favour of traditional engineering approaches. Advancements in modelling the effectiveness of natural landforms in mitigating hazards are helping to alleviate some of this uncertainty. However, policies that recognise and incentivise these broader benefits are also needed.

How Are Nature-Based Solutions Financed?

Despite broad recognition of the severe threats to the global economy posed by climate change, less than 5% of climate finance is currently directed towards combating climate impacts, and less than 1% goes to coastal defences, infrastructure and disaster risk management. Similarly, nature-based solutions are undercapitalised with this lack of finance recognised as one of the main barriers to the implementation and monitoring of these solutions across the globe.

Financing nature-based solutions is complex, particularly for large-scale projects that require substantial investment. The implementation and funding of such projects are subject to market failures and barriers, including information shortfalls (due to the lack of data on the benefits and trade-offs of nature-based solutions, skills and expertise shortages, and a lack of awareness among the general public), a failure to coordinate across public agencies, high transaction costs, long timeframes for financial returns, and greater risk profiles than other comparable investment opportunities.

A large part of the problem is that many of the benefits associated with nature-based solutions cannot be capitalised by any one party or organisation. They create non-excludable benefits and co-benefits that impact many different groups, resulting in a “public good” problem. This often leads to underinvestment in these solutions because private entities cannot capture enough of the return on investment to justify the costs, making it difficult to incentivise private investment in such projects. As a result, it is estimated that only 3% of nature-based solution projects are financed by private capital.

Additionally, financing requires the provision of appropriate risk-sharing arrangements. Typically, these projects are financed through debt, which results in those executing the projects shouldering a significant portion of the associated risk. For example, bank lending and microfinance – the most widely used sources of external funding in developing countries – often impose the risk burden on those who may already be economically vulnerable and least capable of absorbing potential losses.

To scale up nature-based solutions effectively, there needs to be a shift towards financing models that do not solely rely on debt.

What Barriers Are Preventing Nature-Based Solutions From Being Implemented?

Institutional norms and path dependency, where decision-makers tend to implement familiar solutions, also pose challenges to nature-based solutions adoption. Decision-making may be influenced by power dynamics, where choices are driven by interests tied to property regimes that do not support them. In certain cultural contexts, traditional engineering-based solutions are deeply ingrained and shape institutional practices, further compounded by a lack of awareness of ecosystem services provided by nature-based solutions, a lack of seeming responsibility for action, or the discounting of climate related risks.

Overcoming these challenges requires robust institutions, well-established planning structures, and effective processes and instruments to ensure the benefits of nature-based solutions are realised across landscapes and seascapes.

Future Outlook

The growing recognition of nature-based solutions in international policy and business discussions reflects their significant potential to address the challenges of climate change and biodiversity loss. Nature-based solutions can effectively mitigate climate change impacts while simultaneously supporting biodiversity and maintaining the ecosystem services vital for human well-being.

However, their integration into climate and development policies faces three main barriers. First, there is a significant challenge in accurately measuring or predicting the effectiveness of nature-based solutions, leading to uncertainties regarding their cost-effectiveness compared to traditional alternatives. Second, the financial models and economic appraisals used to evaluate nature-based solutions are often inadequate, resulting in underinvestment. Third, existing governance structures are often inflexible and highly segmented, which hampers the widespread adoption of nature-based solutions. Many decision-makers continue to default to engineered solutions for climate adaptation and mitigation.

While nature-based solutions are a promising tool for mitigating climate risk, realising their potential requires overcoming significant economic and political barriers.This, in turn, requires a fundamental shift in how interdisciplinary research is conducted and communicated, as well as how institutions are organised and operated. This includes developing more sophisticated financing models that account for the full range of benefits provided by nature-based solutions, as well as fostering institutional change that supports their integration into mainstream climate adaptation and mitigation strategies.

While they have the potential to facilitate sustainable development within planetary boundaries, their benefits will only be fully realised if they are implemented within a systems-thinking framework which accounts for multiple ecosystem services and acknowledges the trade-offs between them from diverse stakeholder perspectives. As countries revise their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and climate policy increasingly focuses on greenhouse gas removal to meet targets, developing and applying this systematic framework should be a critical focus for future research.

Featured image: Derek Tang.

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us