Toward the end of my interview with Maddie Butler, I can’t help but be distracted again by the strange, serpentine object above her head. Curled, coiled and resembling the shed skin of a snake, the item in question is too tangibly mysterious not to inquire.

Without much hesitation, Butler pulls it down to reveal what can only be described as a hand-sewn film reel of images, or rather film stills, from a video she shot on her phone of her friend playing piano. She printed the images and sewed them together, the resulting piece looking something like a disassembled and reconstructed flip-book, with side-by-side images revealing mere seconds of a moment in time.

“They certainly were inspired by film strips,” says Butler, adding that she just started making the strips and isn’t sure what she’s going to do with them. “I just started making them and I don’t even really know what they are yet or even how I would show them.”

While not entirely representative of Butler’s overall artistic practice, the sewn reel piece is a nice embodiment of the artist’s willingness to experiment with varying and often disparate materials to create something that is both conceptual and crafty. Sure, it wouldn’t be unfair to categorize her as a video and installation artist, but even that encapsulation is limiting and doesn’t fully capture the myriad ideas that orbit her work.

“I think of it all as a constellation, modular” Butler explains, adding that collage is the “foundation” of her artistic practice. “All these little pieces coming together. A lot of my work is gathering these pieces, moving them around, and arranging them into significant compositions.”

Take, for example, “Zip File” (2024) and “Home Movies” (2023), her most recent exhibitions at UC San Diego since moving to San Diego to attend the university’s graduate art program. For “Home Movies,” she created experimental films and digital animations and presented them at the UCSD Commons Gallery accompanied by sculptural fiberglass “window screens” that were meant to invoke the many ways in which we consume filmed media (a cinema, a computer screen, etc.). The video works within the series grew out of Butler’s research into “pre-cinematic techniques of serializing and imposing motion on still photos,” but then using modern technology to create something that conceptually remarks on what she describes as our “screen-saturated present.”

“A lot of people really jump on the technology aspect of the work, which I get and that’s a big aspect of it, but I think at its heart, my work is about human relationships and how we interact and relate to and absorb one another,” Butler says. “The technology has become more and more prominent, because that’s more and more how we’re communicating with one another and sharing ourselves.”

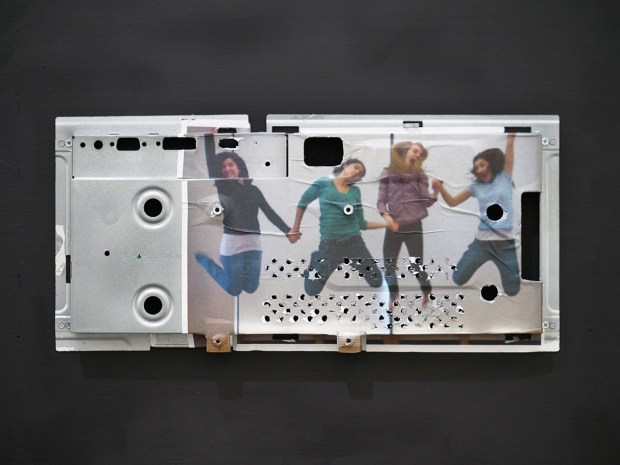

This exploration of the intimacies, or lack thereof, of present-day methods of sharing ourselves was also explored in “Zip File,” albeit in a much more personal presentation for the artist herself. This exhibition, which opened in January at the UCSD Main Gallery, featured startlingly reconstructed photographic works pulled from Butler’s own early days on Facebook from 2007 to 2011 when she was still in high school.

“I put them on Facebook and, like a lot of people, I forgot about them,” explains Butler, who hasn’t been active on the platform much since its early days. “A couple years ago, I thought I should delete it, but there were thousands of photos on there that I didn’t have anymore because I didn’t have the phones or the memory cards anymore. So it had become this extensive archive, both of images and language as well.”

This exploration of social media, and to a larger degree the ways in which we share and communicate using these online platforms, was accented and even punctuated using sculptural techniques in which Butler used disparate objects and items (computer parts, circuit boards, and even pieces of television sets) to create assemblages around and within the imagery. The result is something like a 3-D collage, with the objects and photos working together to present an eerie, almost hypnotizing statement on the ghosts within our machines.

“It’s something that I think about a lot,” Butler remarks. “I wasn’t planning on using those images in my work, but they just felt really potent to me, because they’re so unlike the images that teenagers post of themselves today. It felt really specific to this era where we had these sites and these tools to share these images, but we didn’t totally understand how to use them yet.”

She pauses before adding, “the performance wasn’t solidified yet.”

Much of these images used in “Zip File” date back to Butler’s early life “raised on an island in a lake” in the suburbs of Minnesota’s Twin Cities, where she says her mother encouraged her to follow her artistic inclinations. She says she never gravitated toward a particular medium and that she “tried everything” including collage, ceramics and even painting, but found herself increasingly interested in photographic mediums, including experimental film, once she began attending Yale University as an undergrad.

“I was always into film, but never really thought about making it until I took a video class in college,” says Butler, who began her practice using found footage or video she shot on her phone. “I just connected with it and found that it really came naturally to me.”

She continued working within these media in Connecticut before moving back to Minnesota where she worked at a sculpture park, created sets for theater productions, and even started her own gallery in Minneapolis. After a few years, she landed in Brooklyn for four years before applying to graduate school at UCSD in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I’m so grateful to be here,” Butler says, laughing. “I’m getting paid to have a studio and I have a shop. In New York, even if I just wanted to cut a piece of lumber, it was so hard.”

Looking at her work now, it’s easy to see how these early forays in sculpture, design and collage helped inform her practice. But when viewing her work, one sees someone who is exploring not only video as a medium, but the ways in which we consume, view and interact with what is being presented. Whether it’s on a screen or in a cinema, she’s creating intricate and, pun intended, downright cinematic installation work that is of the moment we’re collectively sharing.

“It’s definitely a process,” says Butler. “When I try to plan the piece, it rarely works. I try to listen to the material a lot and respond to that, or I listen to the space.”

This work has already been popping up in various galleries around town, including a group show called “Primal Instincts” at the Techne Art Center in Oceanside (the show will be up through February 22). On January 9, she’ll present new work at the UCSD MFA Preview Exhibition at the Mandeville Art Gallery, before preparing for her solo thesis exhibition in the same space in the Spring. Finally, she’ll also be displaying new work at the Two Rooms Gallery in La Jolla, alongside fellow artist Enrique Ciapara, which opens January 25.

She describes her thesis exhibition as something of a “continuation” of the themes presented in “Zip File” and “Home Movies,” but also says her new pieces will represent a “merging” of what could have been seen as two distinct styles of works. While “Home Movies” was much more informed by theoretical concepts and research into pre-cinematic technology, “Zip File” was instinctive and personal.

“I think the work is getting more focused, which is good,” Butler says. “I’m still working with a lot of mediums and working on a lot of different things at once, but my thinking around them is more precise.”

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Name: Maddie Butler

Born: Saint Paul, Minn.

Age: 31

Fun Fact: Before moving to San Diego, Butler worked at a nightclub in New York City creating elaborate set pieces for large warehouse dance parties that would be destroyed sometimes the day after they were installed.